Most firms say they have a strategy, and maybe even boast about how clever it is. Yet few manage to sustain even average growth—in sales, market share, or profits—for any length of time. Many just bumble along, always fighting fires but never gaining ground—and rapidly disappear.

It’s rare for any company to redefine the rules of the game in its industry. Or achieve a high rate of innovation. Or build a winning team. Or build standout brands. Or consistently deliver exceptional customer experiences. And watch how many seem always to be in turnaround mode, with change experts swarming all over them, projects everywhere, and no actual fix ever achieved.

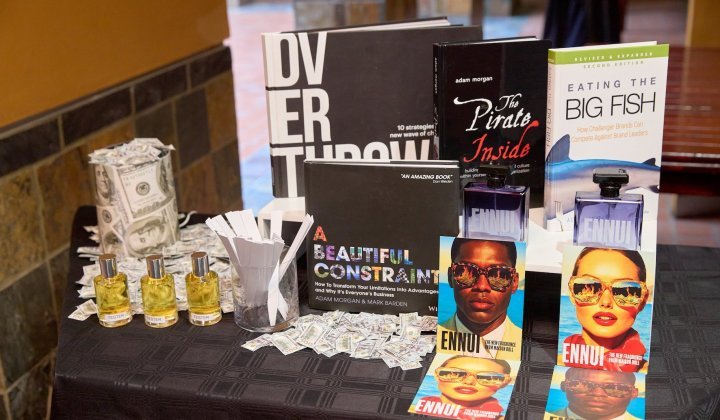

This is odd, given the massive surge in strategy books and articles in recent years, and in business school strategy teaching. And in the large number of academics and consultancies advising firms on the topic. And let’s not forget the hordes of wannabee gurus — writers, speakers, trainers and so on — who have something to say about it. Or the executives who want to promote themselves or their companies by sharing their success secrets. Or the athletes, adventurers, social media influencers and others who similarly seek fame and fortune through their fatuous explanations of how to succeed.

There’s glut of advice about strategy. There are more insights, theories, checklists, models, and frameworks than anyone could wish for. So managers are spoilt for choice, and often hopelessly confused about what to expect from strategy, which tools to use, and how.

They’re not helped, either, by the fact that the latest “research” supporting a particular approach is often neither rigorous nor useful. Since storytelling became a big deal many years ago, we’ve been told any number of tales about “Ben” or “Sasha”, “Thuli” or “Jeff”, and how they built a business, fixed a firm they led, or conquered new markets using this or that wonderful tool or approach. But what really enabled their success? Will it do the same for other executives who drink the same Kool-aid? Maybe, but probably not.

The performance of a company depends on four Cs — the context in which it operates, the choices leaders make about everything they do and the way they do everything, the concepts (philosophies, ideas, theories, tools) they use to get results, and the everyday conduct of the people. So singling out any factor as being the cause of success is extremely difficult, if not downright impossible. What’s achieved is the product of a tangled web of factors, rather than pulling one lever or another. There’s only so much that any executive can control or take credit for.

Besides, while much of what’s on offer by the management ideas industry is touted as “thought leadership”, most of it is more accurately described as “thought followership”. The same old ideas are tweaked, rebranded and recycled again and again. There’s a thimbleful of stuff that’s really necessary, and a minefield of hype, mumbo-jumbo, unfounded assertions and misleading “must-do’s” that might be entertaining and lead to a lot of happy talk, but can safely be ignored.

Another reality is that more strategy tools are of a “technical” or “mechanical” nature than those of most other managerial disciplines. Strategy is an intensely human function. But because it involves risk and requires analysis, choices and trade-offs, it makes sense to bring graphs, charts, matrices and spreadsheets to the task. These, along with value chains, strategy maps, balanced scorecards and project plans, inspire confidence that the future is predictable and success can be assured. Just crunch the numbers and tick the boxes; no thinking required!

Strategy is the most critical of all executive functions. But it has been democratised, commoditised, and bastardised like no other business discipline. The term is attached, with no concern for its meaning, to vague intentions and specific goals; to plans, projects, activities, and roles. Companies have “strategies” for everything; nothing is left to chance.

Nor is actual experience required for someone to be called a strategist: the title is often just used to attract a new employee, or as a pat on the head or a substitute for a pay rise or promotion. So not surprisingly, anyone and their dog feels confident about spouting advice on strategy. People who’d hesitate to venture opinions on HR, IT, procurement, logistics and other key disciplines don’t hesitate about holding forth on this, the function that informs all others.

Because of this, I often bang heads in strategy sessions with someone who is not in a meaningful strategy role, or clearly has a superficial knowledge of the subject, who tries to tell me why the approach I’m advocating is wrong and what I should do instead. “Let’s talk about our purpose,” they’ll tell me. Or, “We need to find a blue ocean.” Or, “We have to be disruptive” or aim for “shared value”.

They may have a point. As company insiders, they may have an invaluable take on things. But a little knowledge can lead to a lot of confusion, fruitless work and needless costs. And there are many ways to skin the strategy cat.

What’s more, these individuals can make a nuisance of themselves back at work by challenging everything that’s said in strategy discussions, second-guessing decisions and banging on about whatever approach or tools they favour. The Dunning-Kruger effect on reckless display!

Strategy is not a plug-and-play or paint-by-numbers task. The formula doesn’t exist that will get you from where you are to where you’d like to go if you just follow the instructions. Buzzwords do not lead to high performance.

That said, knowing what’s necessary and settling on a well-founded approach and a strategy toolkit with just a few tools in it would be a big step up for most managers. Instead of flailing about for the latest answer to their problems and fumbling with this or that hot new fad, they could spend their time with their people, or out in the field talking to their customers, watching their competitors, and thinking about how to seize new opportunities.

Strategy is essentially a communications tool — a point of view about where and how you’ll compete. It should help you focus your organisation’s resources — not just money, infrastructure and capabilities, but also time, attention, and energy — on the actions most likely to bring success.

Peter Drucker told us about 60 years ago that leaders must constantly think about what their business is today and what they want it to be tomorrow. And doing this requires that they address three key questions:

- Who will we serve?

- What value will we deliver?

- How will we do it?

As simple as that. And to this day, nothing has changed.

It’s also worth considering these views from three of today’s most influential experts:

- “Strategy is a way through a difficulty, an approach to overcoming an obstacle, a response to a challenge.” (Richard Rumelt, author of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy: The Difference And Why It Matters)

- “The primary purpose of a strategy is to inform each of the thousands of things that get done every day, and to ensure that those things are all aligned in the same direction.” (Michael Porter, Harvard Business School)

- “Strategy is the smallest set of choices and decisions sufficient to guide all other choices and decisions.” (Eric van den Steen, Harvard Business School)

The point is, strategy is not rocket science or an esoteric subject that only the most senior executives can understand or be trusted with. Rather, it’s a practical matter, whose fundamental purpose is to tell Annie or John or whoever else what to do today.

Making good choices quite rightly gets a lot of attention in strategy-making. This, after all, is the sexy part, involving foresight, creativity, argument, vision, courage and so forth. And being described as “a great strategist” hinges almost entirely on an ability to create apparently brilliant strategies.

But that’s by no means enough. Choices are only as smart as the actions they trigger. And countless studies show that strategy execution is much harder than strategy design, so many “good” strategies wind up failing.

Often, when chief executives have briefed me on their strategy needs, they’ve told me: “We need a moonshot. Some fresh thinking. More innovation. Out-of-the-box, blue-sky stuff”. But when I dig into their businesses, I usually find that they’ve mis-identified the problem.

Their real challenge is not to cook up a new vision or mission, but rather to execute their strategy properly. To make “the difference that matters” that they promise to their customers. And job number one is to be sure they’ve got the basics right — to “fill the tank and pump the tyres” — so they don’t let profits fall through the cracks, and have a well-oiled business with which to pursue their future dreams.

As an outsider, I can often put my finger quite quickly on what’s really troubling a firm, and what must be done to improve its performance. My know-how and independence enables me to objectively challenge the assumptions, politics and practices that hold it back and to see possibilities where they only see problems. I can ask the “right” dumb questions and press for clear answers when there’s bullshit in the air.

But I’m also aware that I can’t possibly know as much about a company as the people inside it. I will never fully understand what’s in their heads as I was not around as they travelled to where they are today. And I respect deeply what they bring to strategic conversations and the value in bringing them into those conversations as early and often as possible.

Becoming a strategist does not happen overnight. It’s not as simple as taking an MBA course or reading a book. It takes years of learning and practice, special qualities of insight, foresight, intuition, imagination and judgment, plus the ability to synthesise a range of facts, opinions, ideas, impressions and memories. It also requires an acute sense of the context in which strategy is being made — of world affairs, customer and competitor behaviours and so on, which make certain choices sensible or risky. And it requires a deep and wide grasp of management thought and practice, so that smart decisions can be made about which tools to use, and how best to use them.

My purpose is not only to help companies solve tough strategic problems, but also to help their people develop the strategy wisdom that will help them solve those problems for themselves.

And to encourage them to practise, practise, practise to develop their competence and confidence.

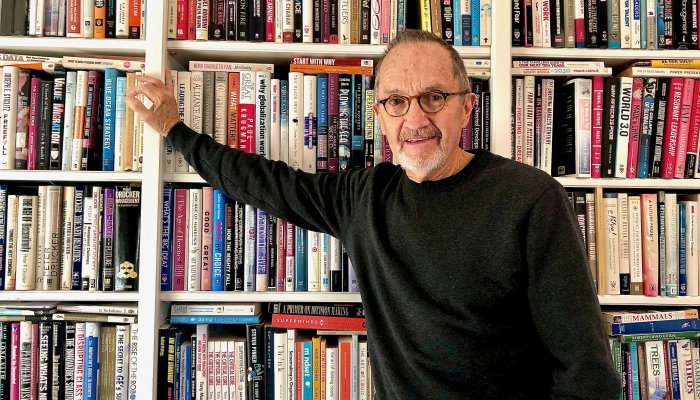

Tony Manning has been an independent strategist since 1987. He’s the author of 13 books and many articles, and lectured on strategy for 18 years at GIBS. He was previously chairperson and chief executive of the McCann-Erickson advertising agency in SA, head of marketing at Coca-Cola (Southern and Central Africa), and chairperson of the Institute of Directors.