Understanding the impact of retirement on South Africa’s public company CEOs was the focus of Dr. Mark Lamberti’s Doctorate in Business Administration (DBA). He wanted to research the difficult transition these highly accomplished people face upon retirement.

“All of us face retirement challenges, but there are some factors that exaggerate that transition for CEOs,” he says.

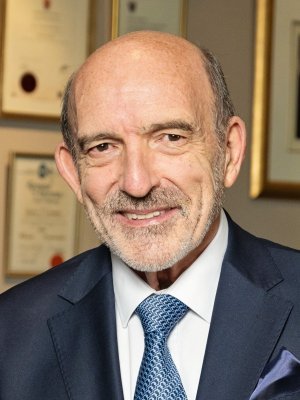

Lamberti, former CEO of Massmart, Transaction Capital, and Imperial Holdings, retired from thirty years of public company leadership in 2018, before embarking on his DBA. He, and his research supervisor, GIBS’ Professor Charlene Lew, chatted to Acumen about the importance of planning the transition into retirement.

The journey to a new identity

Retirement is not merely another phase in life, notes Lamberti. It is the redefining of those elements of one’s career identity that are so intrinsically linked to self-worth. He explains that careers give validation and are a source of achievement. They offer structure and purpose as well as social belonging and status. And, when people stop working, all of that is taken away.

Lamberti explains that, on retirement, CEOs face a significant risk because of their potential over-identification with their jobs.

He says, “Very few people have a more definable identity than a public company CEO. They are in the public arena. They are seen and acknowledged on the basis of their title. They are assessed on the basis of the performance of their company. They have a huge infrastructure of support under them, and they have a social network that is largely about the job.”

CEOs who have managed to maintain multifaceted dimensions to their lives, however, are better equipped to deal with retirement, notes Lamberti. He describes them as people who have interests outside of work, something beyond their business cards – those with good social lives, who enjoy sports, have hobbies and pastimes, or who define themselves as spouses, and/or parents.

Because of this, Lew, who holds a PhD in Psychology, urges people to thoroughly prepare for retirement by leading a balanced life before retirement.

She says, “One cannot start building the different blocks of one’s life after retirement. How one lives beforehand will determine how rich ones life can be thereafter.”

So while all CEOs will, invariably, grapple with an unsettling lack of identity, Lamberti says that the people in real crisis are those who dedicated themselves exclusively to reaching the pinnacle of one firm over 30 years, and on retirement are forced to question who they are, as they are faced with a devastating void – a loss of corporate, career, and personal identity – that they don’t know how to fill.

The void

Lamberti explains that on retirement, CEOs find that their diary – once filled for months if not years in advance – is empty. The external cues of appointments, emails, and calls fall off sharply, and people don’t respond as fast as they once did. Their private network may also not be available to them in the way they hoped. Their spouses, while supportive, have likely built their own lives, their children are adults with their own priorities, and friends may still be working or may have retired to a new location.

“One of the things that strikes them as they come out of this physical and psychological displacement from their CEO role, is this void. They find themselves in an ‘empty’ place,” says Lamberti. It is a profound feeling and can result in a great deal of anxiety and introspection for former CEOs.

He adds, “This void leads to something which we never touched on in the research, but it is a real issue. This is the fact that because identity is such an important part of self-worth, a massive change like retirement can have a negative influence on one’s mental health.”

While the focus in Lamberti’s research was on CEOs, Lew stresses that this research is relevant to anyone who is looking to retire in the future.

Two phases of retirement

Lamberti’s research identified two distinct phases CEOs are met with when they retire, and which can take up to two years to navigate.

The first phase, “liminality”, is where people find themselves in uncharted territory. “They are trying to understand where they are, and are trying to come out of this physical and psychological void,” says Lamberti. They are hovering between two distinct realities of life, that of being a CEO and that of being a retiree. However, Lamberti says, “This phase ignites cues that drive the creation of their new identity. What are the things that they want in their new life, and what do they not want?”

The second phase is “role identity emergence”, where the retired CEO starts to construct a bridge between their old and new lives. Lamberti says, “One CEO said to me that it was quite difficult. It was an iterative kind of conversation, an internal one.” Lamberti explains that the decisions in this phase are not clear-cut or obvious: people start experimenting, finding out what works and what does not. It can be an extremely confusing time.

Lamberti says that this phase in the CEO’s life is probably the first time that they ask the existential question of, “Who am I?”

He adds, “The learning for me is that this process is about seeking meaning in your new life with authenticity.” He explains that people need to continue building on their lifetime of experience, education, and achievement in business, but concurrently, they need to identify what will give them meaning and purpose.

Lew stresses that newly retired people must use the resources available to them to make a difference. She says, “Every leader should think about what they have and how they want to bring that to the world. Resources allow leaders to drive change in areas that go beyond their organisation and their personal lives.”

The CEO’s toolkit: The six Ws

Both Lamberti and Lew stress that preparation is key to a successful transition. Lew says, “When we look at retirement, everyone considers financial preparation, but we should also prepare psychologically for the journey that lies ahead.”

Lamberti’s research identified six questions that CEOs need to be able to answer before they start on this journey. In fact, Lew stresses that everyone should revisit these questions regularly throughout their career:

- Who am I?

This is the big existential question. Who are you beyond your identity of your job title? - What am I going to do when I retire?

Are you going to consult, mentor, study, travel, play sport? This question delves into the activities that will fill your day. Lamberti warns, however, not to make your current leisure activities the focus of your plan, as that will not be sustainable. “After all leisure is only leisure because of work!” says Lamberti. - Who am I going to do it with?

Have you forged mutual interests with your spouse, family, and friends? Are there people who share your interests and work with you? - Where am I going to do it?

Are you going to retire to the coast, emigrate to be closer to your children, or remain in your current hub of activity? - What resources do I have to use to do it?

Resources include, money, networks, education, infrastructure, anything that you can use to conduct the activities that you will take on after retirement. - What is my purpose?

This is an extremely important question. What do you want your legacy to be? How are you making a difference in the world and what form will it take?

Lamberti warns, however, that there will be a “convergence of age with the discovery of a new life”. Older people will not be able to embark on new activities with the same energy and vigour as they could when they were younger.

Lew urges people to spend enough time working through these questions. She says, “While these questions offer a profound opportunity for reflection for a public company CEO, they can be equally profound for people retiring from less complex contexts. They are significant personal questions to answer.”

Advice to those retiring

Lamberti says, “My first piece of advice is for people to relax. Answers are going to come to you over time and the redefinition of one’s own identity is something that takes time.” He urges people to read, and to write. “I absolutely, unequivocally, and implicitly believe in writing. Until it is written down, it is not subject to scrutiny, not subject to debate. Write for yourself, journal your own fears. Don’t panic. Think, write, but don’t go into seclusion,” he says.

Lamberti adds a few additional points to his advice list:

- Be positive.

- Don’t use the word “retirement” because it implies you stop doing things.

- Look forward to this phase in life as it is an extremely joyful time.

- Start planning no less than five years beforehand.

- Remember that your title did not and does not define you.

- Find happiness through health, purpose, making a positive contribution, and making a difference.

- Forge strong relationships.

- And finally, remain humble. You must accept this new reality and your new place in life.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- The transition from a career to retirement can be devastating for anyone who has not planned for it.

- The transition, which creates a massive void, requires a complete re-evaluation of the personal identity.

- CEOS are met by two distinct phases when they retire – liminality (being in uncharted territory) and role identity emergence (building the bridge between your old and new life).

- People at all stages of their career must ask themselves the six “W-questions”.

- Retirement should be approached with a positive mindset and excitement.

Prof. Charlene Lew

Prof. Charlene Lew is a full professor at the Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS). She holds a doctorate in psychology and teaches on behavioural science, change leadership and strategic and ethical decision making. She serves as chair of the GIBS Ethical Business in Complex Contexts research community. Her consulting firm PsyQuenza focuses on behavioural change interventions and customised assessment and intervention development.

Dr. Mark Lamberti

In 2018 Mark Lamberti (75), transitioned from a 33-year executive career as CEO or chairman of various private and public companies to a plural portfolio of directorial, academic, and philanthropic assignments, while guiding his family office as chairman of Lamberti Holdings. In April 2024 Mark was conferred with a DBA through GIBS. This sharpened his focus on education as a benefactor, governor, director, and lecturer, while enabling participation in mainstream scholarship.