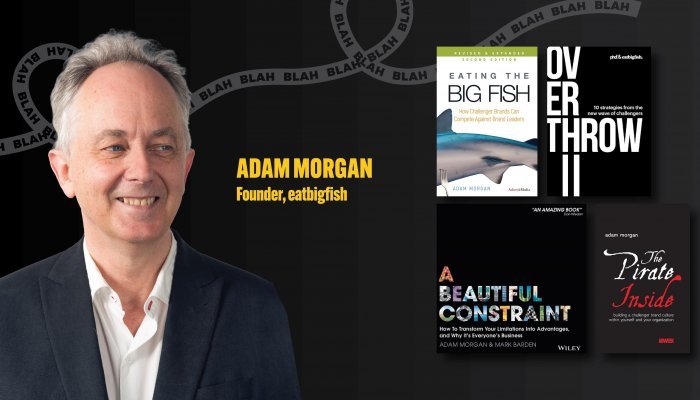

When Adam Morgan, founder of strategic consultancy eatbigfish presented live from the UK to an audience of media and marketing executives at GIBS, he brought with him not only his latest research but also his reputation as one of the most provocative thinkers in brand strategy.

Morgan is best known as the visionary author of Eating the Big Fish, the book that put the concept of challenger brands on the map. He is also the host of the consistently popular Eat Big Fish podcast, where he interviews global creatives, entrepreneurs and business leaders on how to challenge convention and build distinctive brands.

In his South African address titled "The Eye-Watering Cost of Dull", Morgan put forward the notion that creating dull content is much more expensive than we realise. It’s expensive financially because dull brands have to spend more to get noticed. It’s expensive culturally because dull corrodes energy and curiosity inside organisations. And it’s expensive in terms of trust, because in today’s world, dull doesn’t feel safe – it feels indifferent. And if you feel nothing, you do nothing.

Indifference is an extraordinarily prevalent problem, says Morgan referring to the results of System1 Group’s “Test Your Ad” study, which tested 55 000 television advertisements that had been run in the UK since 2017. One of the ways in which they test is to ask the viewer what emotion it made them feel. The most common feeling was “nothing at all”.

“We know that emotion is essential commercially but we are just not responding to it or using it in the right way. I want the marketing and communications business to look much harder at the vast tide of dull and mediocre stuff we’re putting out all the time and be much less tolerant of it,” says Morgan. “I want, by putting a concrete figure on how much it actually costs us to be dull, to make us realise we just can’t afford to do that as responsible business owners anymore.”

The financial cost of dull

The data backs him up. Morgan points to research from Peter Field – one of the foremost experts in marketing – using cases from the IPA Effectiveness Accreditation. “I asked Peter: what if we could take the principle that the pain of losing something is twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining something, and look at the cost of that loss? What are we losing by being dull?

“Peter split the cases into two kinds: those that succeeded by using rational persuasion and those that sought to be famous, emotionally engaging, emotionally exciting. He looked at, for the same commercial return, how much more it cost the dull cases to succeed. And it cost them on average over seven extra points in extra share of voice (ESOV), which in the UK amounts to roughly £10 million. That’s to say, dull content can still be successful, but you have to spend £10 million more in media to get there.”

The next question was the cost of dull TV advertising for US brands. Research showed that the estimated annual spend over current levels needed to match non-dull ads’ market share growth was roughly $190 billion. That’s staggering!

As David Blyth, founder of DeltaVictorBravo, the Africa partner for eatbigfish, reminded the audience: “The data is there. What are you doing about it?”

A provocation for change

Morgan doesn’t deny there are reasons brands might choose dullness.

“You might be risk-averse or you’ve got more money than you know what to do with. If so, fine. But most of us don’t. We all wake up wanting to do the best for our brand and our clients.”

To bring it home, he recalls how cinema adverts were tested in 1960s Los Angeles. Audiences had just one dial: very dull, dull, normal, good, very good. That was it. “Perhaps in our rush to create ever more complex metrics, we’ve forgotten the one that matters most: is it dull or not?”

Are people really seeing your ads?

Dr. Karen Nelson-Field, one of Morgan’s collaborators, believes dullness is about the ability to hold and retain attention. Active attention is looking directly at what is being shown to you. Passive attention is looking nearby, not directly at it. No intention is not looking nearby at all. Being served an ad is not the same as seeing the ad at all – and in that gap is a huge amount of media waste, she says. “Measuring active attention, rather than just viewability, is the thing we should be looking at,” explains Morgan. “Memory structures, which are essential for brand building, require at least 2.5 seconds of active attention to form. Anything less and the impression simply doesn’t stick. If you’re a market leader with strong assets, maybe you can get away with it. But if you’re a challenger it’s fatal.”

Five questions all businesses should be asking

Are you creating dull content? To pressure-test important projects or campaigns against the real standard of attention, Morgan suggests taking your key initiative for the year, scoring it 0 to 10 against each question and then asking yourself: where could I push harder? Where could I create more drama, more surprise, more connection?

1. Are we meeting them where they care and speaking their language?

Too often, brands assume audiences are as interested in their category as they are. They’re not. “In the UK, 56% of people can’t think of a single brand that they feel connected with or that understands them,” Morgan notes. The challenge is not just to say something, but to say something that feels like it matters in the context of people’s real lives.

He gives two examples. First, Richard Curtis’ edit of the film Bridget Jones’s Diary. Test audiences initially didn’t laugh at what was supposed to be a comedy. Why? They didn’t connect to Bridget. “So Curtis took a scene of Bridget sitting in pyjamas, drinking too much wine, eating ice cream from the tub, singing melodramatically to All by Myself from the end of the movie and moved it to the very start of the film. It transformed the audience’s connection with her, because suddenly they thought: ‘Ah, I’ve been there.’”

Second, Pampers and its “Don’t fear the Poonami” campaign.

“If you’ve ever changed a nappy, you know exactly what that moment is. It’s universal. It gives you that smile of recognition – and that’s the smile that says, this brand gets me.”

The takeaway? Connection isn’t built through demographics or rational claims. It’s built in those little flashes of human truth and through the power of laughter. We have to try much harder than we think to really create that connection.

2. Are we telling them something they already know or denying one of their assumptions?

Dull communication confirms assumptions. Interesting communication challenges them. Audiences want to be surprised. The problem is, in today’s personalised, algorithm-driven world, surprise is being engineered out – but herein lies an even bigger opportunity for brands. Morgan argues that the best work actively denies what people think they know about a brand or a category. It unsettles expectations, nudges behaviour and forces a rethink. What’s the one assumption about our brand or category that would benefit us to challenge? And what new behaviour could we prompt by surprising people?

3. Are we using emotion, drama, and storytelling?

Here Morgan circles back to where his project began – with Sesame Street. “I interviewed the head writer of Sesame Street and asked him how they managed to get preschoolers interested in numeracy and literacy – something professional educators said was impossible. He told me it’s easy to get anybody interested in anything if you create little dramas. And there are two parts to drama: you must know what the character wants and you must know what’s in the way.”

That tension of want versus obstacle is the essence of a story. Brands that thrive are led by people who know both answers: what the brand wants and what stands in its way. Brands that drift lack clarity on one or both. How can we bring what we want and what’s alive in a way that creates drama? How do we let people feel the struggle, not just hear the facts?

4. Are we sharing real distinctiveness and character?

Distinctiveness is one of the most discussed – and misused – words in marketing. And it’s not about a logo; it’s about real character. Take the example of Renault adding a baguette holder to one of its car models. Quirky? Yes. Ridiculous? Maybe. But it created a distinctiveness people remembered, smiled at and associated with Renault’s Frenchness. What single, ownable trait can we amplify until it’s impossible to ignore?

5. Are we judging against the right bar?

Many teams fall into the trap of benchmarking their work against the category. “We often ask, is this good enough? Is this as good as what the rest of the category is doing? However, the real bar is not whether your ad is better than your competitor’s, but whether it’s more interesting than the thousands of other stimuli people are bombarded with every day. That’s the only standard that matters,” says Morgan. Are we honestly measuring ourselves against the real competition for attention or against a safe, internal standard of “good enough”?