For centuries, the brain and its workings have been mysterious, but the veil is starting to lift. Until now, attempts to fathom how the brain works have veered towards hocus-pocus, but now the relatively new discipline of neuroscience holds the promise of introducing the rigour of science into this whole area, enabling psychology to become truly scientific.

...emotion acts as a powerful and often unrecognised factor in motivating staff.

Neuroscience uses sophisticated medical imaging technology to observe which parts of the brain participate in decision-making activities. Understanding how the various parts of the brain work together enables scientists to understand the hidden mainsprings of why humans act as they do.

For business, the obvious promise is understanding why customers make the decisions they do, and thus become better placed to influence that process. Less obviously, perhaps, neuroscience could provide the wherewithal for leaders to improve their own thinking, and so solve problems better.

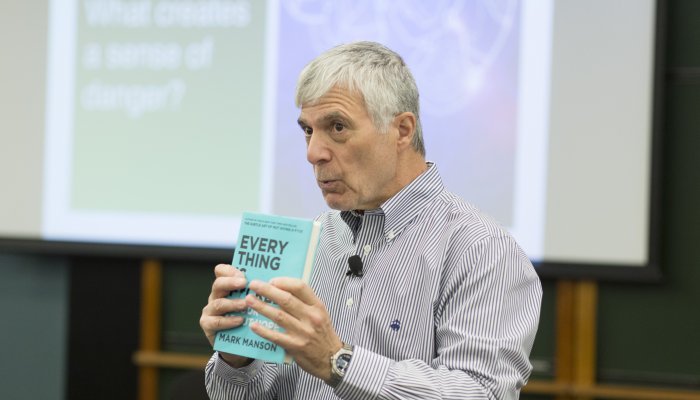

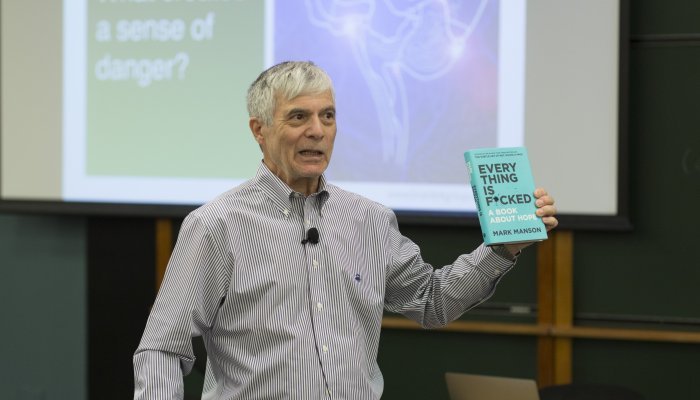

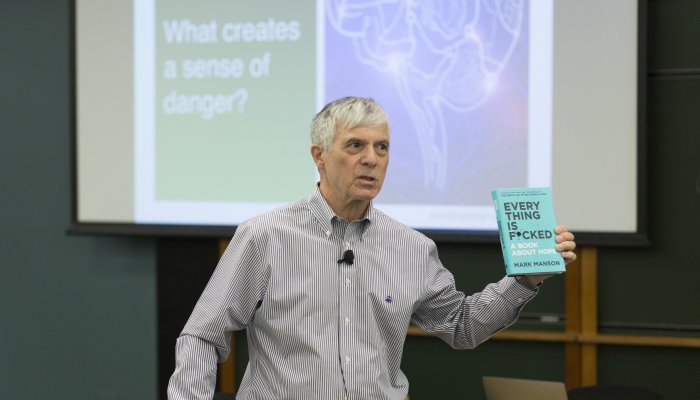

Former South African Dr. Norman Chorn is an economist and behavioural science expert. Now based in Australia, he uses neuroscience and economics extensively to help clients develop strategies and solutions in highly complex environments. He says the brain should be understood as two different, but linked, systems that produce different types of thinking. The limbic system is the older of the two, and, in essence, relies on memory and habitual responses. Its operations are largely non-conscious, and it can process large amounts of data. It produces decisions quickly and automatically: That guy has a gun; duck behind the building and run.

By contrast, the pre-frontal cortex is a much newer part of the brain. It produces conscious, rational thought, but it has limited processing capacity.

Simplistically, the former offers quick but sometimes sub-optimal decisions. The latter is much slower and requires more effort but is likely to result in higher quality decisions. These processes are highly complex, of course, and involve some of the same parts of the brain, but the essential dichotomy between non-conscious, instinctual, pre-programmed thought on the one hand and conscious, strategic thought on the other holds true.

“While many argue that psychology may lack objective evidence of cause and effect, neuroscience is more reliant on scientific evidence and observation. However, the two are interdependent, as psychology often provided the underlying theory to explain some of the observations made by neuroscience,” Chorn points out. “It is helping us to understand why humans make the decisions they do.”

Rita Doherty, chief strategy officer at FCB Africa, makes the important point that one should distinguish between neuroscience – the science of how the brain works – and decision science, which essentially extrapolates from neuroscience to understand how decisions are made. According to Doherty, business – and certainly advertising – is most interested in the latter.

...the obvious promise is understanding why customers make the decisions they do...

Understanding consumer behaviour and decision-making

One of the key insights that neuroscience has yielded is that emotion plays a key role in conscious decision-making. This insight is based on the observation of brain activity, which shows that the amygdala, which is the seat of emotional processing and thus associated with the limbic system, also affects rationality. This flies in the face of much business and economic theory, which assumes that humans make decisions rationally.

In Descartes’ Error, Antonio Damasio cited a study showing that patients with a damaged amygdala were still able to think and reason logically but were incapable of making decisions. “If you can’t feel, it is hard to make decisions,” Doherty says. “This is a completely new model of decision-making.”

What’s frustrating, she adds, is that the model of rational decision-making remains dominant, even in business schools. She even wrote a book, The Big Easy: Scientific Marketing & The Creative Instinct, in which she explains the concept to clients.

Even when it comes to conscious decision-making, emotions are important because they “tell” us what is important, adds Ryan Parkhurst, head of marketing at Investec Wealth and Investment South Africa. “Your prefrontal cortex won’t pay attention to something unless the amygdala or hippocampus (the seat of memory) validate its importance,” he says. “We tend to make decisions emotionally and then justify them rationally rather than the other way around. The reason is curiously handicapped without emotions.”

For example, the apparently rational process that would be used to decide who should manage one’s money will be influenced by the trustworthy (or not) appearance of the individual. This raises ethical issues, particularly when it comes to marketing to children or uneducated people.

Now that electroencephalogram machines are easily and cheaply available, Parkhurst says, it is increasingly easy to research exactly how any marketing approach is actually affecting the brain, and thus the decisions it takes. In other words, the business of influencing consumers is becoming more and more accurate.

Both Doherty and Parkhurst say that another big insight from neuroscience has been the human predisposition to easy decisions. For example, says Parkhurst, Coke has learned that building brand loyalty is not as important as it once thought. Instead, it is more important to ensure that the product is easy to purchase, hence its emphasis on distribution. This is borne out of studies by Nielsen and TNS which show that the largest percentage of Coke sales in both the United States and the United Kingdom are to people who drink one or two a year, whereas the brand loyalists who drink one a week account for under 1% of sales.

FNB’s campaign promising to help clients switch their accounts easily and quickly played to this particular gallery, as do most of the ads for unsecured loans.

...the danger is always that the easy, powerful and seemingly intuitive limbic system is apt to take over.

Better leaders

The decision aspect of neuroscience also has value for corporate leadership strategies. At the most basic level, understanding how people make decisions makes it much easier to get them to act in certain ways. Here, too, emotion acts as a powerful and often unrecognised factor in motivating staff. It can also help greatly in notoriously tricky projects such as change management, says Chorn. Leaders can also use the principles of neuroscience to predict how competitors will act in the tactical, operational sense.

But he believes the real benefits will be found to lie in the still-embryonic discipline of neurostrategy, which uses neuroscience to help leaders think more strategically.

It will be clear that the two modes of thinking and decision-making briefly described above – the instinctual and the conscious – are both useful in business. But, the higher up the organogram one goes, the more important the latter is. Trouble is, it’s the more difficult of the two, and the danger is always that the easy, powerful and seemingly intuitive limbic system is apt to take over. We can all agree that we live in a volatile, unpredictable, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) world, and thus a high premium is placed on leaders’ ability to navigate it. At the same time, these very conditions make it hard to think strategically as the pressure to do something or to make a decision is unrelenting.

“Currently, there is an overemphasis on speed. Think of ‘business at the speed of thought’ and we are in danger of killing off strategic thinking,” says Chorn. The problem is that quick thinking inevitably relies on a narrow repertoire of action derived from the past, and thus one runs the danger of endlessly repeating the same mistakes.

The goal is to use neuroscience to improve the ability to think strategically under pressure. Although it is a complex area, there are some extremely practical ways of going about changing the way one thinks (see box). First up though, says Chorn, we need to recognise that changing established patterns of thought is extremely difficult, not least because of what is known as Hebb’s Law, which postulates that mental pathways that are repeatedly used become physically associated with each other. The more we use a certain path, the easier it becomes to use. It essentially shows how a mental “habit” actually causes physical changes in the brain.

That said, though, the more we consciously use conscious, rational, purposeful thinking (as opposed to the easier instinctive approach) for problem-solving, the easier it will become.

Neuroscience is already being used to good effect in sales and advertising. The next frontier is to use its insights to address the trickier area of strategic thinking and problem-solving.

Five steps to boost strategic thinking

Dr. Chorn has developed a five-step methodology for helping leaders to use the scientific understanding of brain function to improve their ability to think strategically.

1. Understand the history. Do research on any similar situations in the past, how they were resolved and latest thinking.

2. Immerse yourself. Gather as much information as you can about the situation and the key players involved. However, an important part of this process is developing a “beginner’s mind” to enable you to listen to this first-hand information in a non-judgemental way. It is important not to jump to conclusions but to rather observe everything you can.

3. Retreat and ‘calm’ your brain. Block the flow of visual and auditory information related to the situation. This process will enable your brain to process all this information and unconsciously make new connections – the “insight” we are looking for.

4. Mentalise the situation. “Mentalise” describes the objective, systems-thinking approach that good strategic thinkers adopt.

5. Reject binary solutions. Chorn argues that binary solutions are the hallmark of reactive rather than strategic thinking. “Force yourself to generate as many alternatives as possible, which will increase the chances of generating a creative insight that breaks the logjam in the situation,” he says.

Adapted from Dr. Norman Chorn, “Boost your strategic thinking” (Brainlink Group).