The boxer who drags his bruised body up off the canvas to retain his title... Roger Federer for his 18th Grand Slam title at age 35 after knee surgery and five years without a major title... In business, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs’ return to lead the company to the word’s first trillion-dollar valuation after his ousting and fall from grace in 1985 transformed him from tech billionaire to business and cultural icon.

The coronavirus-induced economic crisis made all of us underdogs in the course of a few days in the opening quarter of 2020. That makes all of us potential comeback stories that will one day define our business careers.

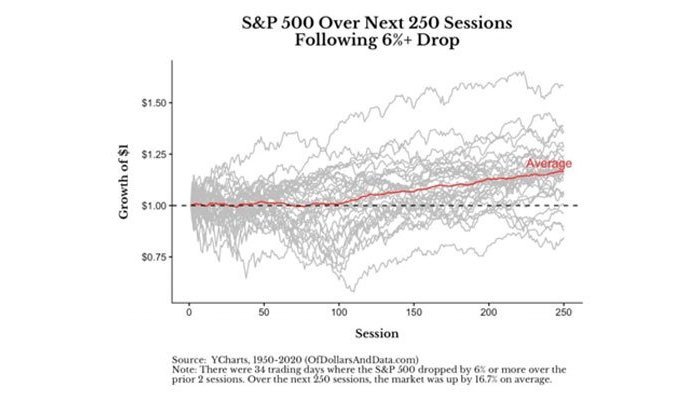

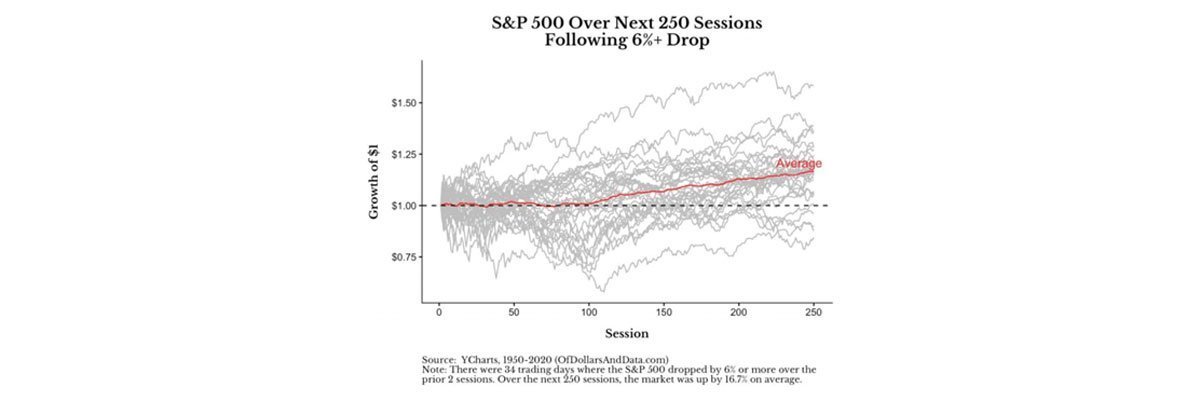

Figure 1 – If we need hope that there is light at the end of the financial tunnel, we should recall that markets do come back. A graph tracking US$1 invested in the S&P 500 for 250 trading sessions immediately following the 34 occasions when the index dropped by 6% or more in a session portrays this phenomenon.

...all of us [are] potential comeback stories that will one day define our business careers...

Boxing or business, every comeback is a function of the depth and breadth of both the plunge and the revival that follows. The novel coronavirus took us deep and wide. GIBS professor and economist Adrian Saville captures the recent plunge: “We are in the fog of war. And unlike any other crisis I have seen, this includes everyone across the world. Even the great upheavals like the collapse of the Soviet Union were localised to a degree. The 2008 global financial crisis was, of course, global, but it was financial rather than social and seated in the real economy.”

The genuine universality of this crisis demands that business owners, managers and executives tackle the challenge from multiple angles. Here we pool the advice of experts in the GIBS community from fields as distinct as international trade and branding to help spark ideas as you navigate your own comeback.

A new abnormal

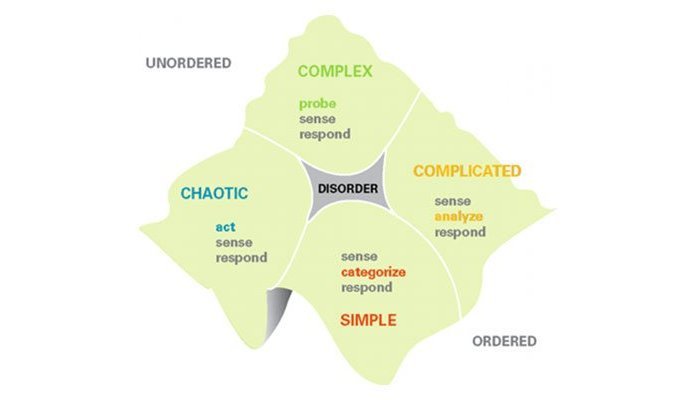

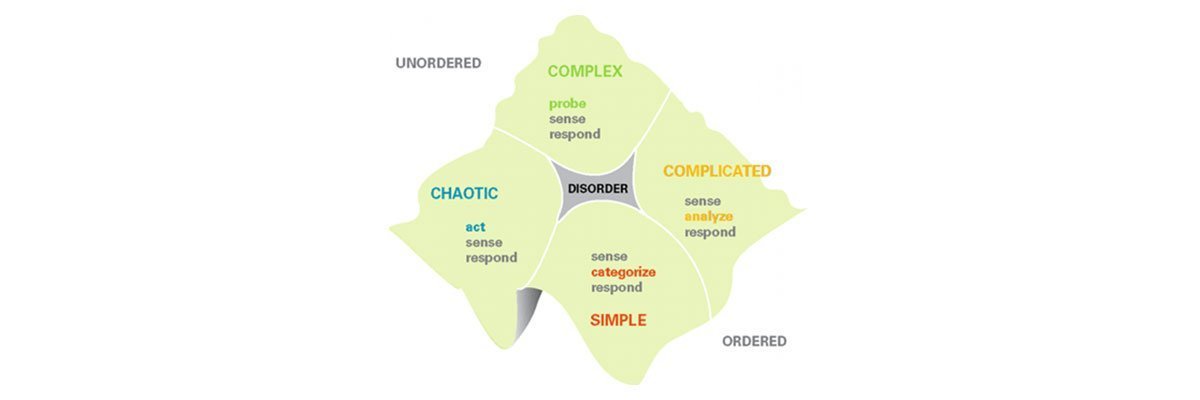

The coronavirus has yanked away predictability from many of our business decisions. From revenue streams to regulation, our hard-earned systems of analysis and forecast no longer apply the way they do during business as usual. In these cases, doubling up on analysis is futile. David Snowden, the renowned Welsh management consultant who wrote the iconic text on managing in vastly different contexts, argues for a categorically different approach to decision-making in the face of this complexity. In his words, “Leaders who try to impose order in a complex context will fail, but those who set the state, step back a bit, allow patterns to emerge, and determine which ones are desirable, will succeed.”

Figure 2 – Businesses will face many decisions in the 'complex' segment of David Snowden's model during the comeback from COVID-19. This demands a change in tactics from what works for more ordered, predictable decisions. (Image: Harvard Busines Review)

GIBS faculty Dr. Jill Bogie elaborates: “When there are such deeply interconnected systems at play, we can’t sensibly evaluate cause and effect. There is too much turbulence. The beauty is that there are no right or wrong answers. Leaders need to be able to recognise where this is the case and go into action mode. Try things and do more of what seems to work.”

Managers can take heart from this. The best of us face unknowns that we can’t possibly know, no matter how hard we try. We’ll do well to embrace the uncertainty, identify decisions where analysis will only cause paralysis, and learn as we experiment – in Snowden’s words, “probe, sense, respond”.

...doubling up on analysis is futile...

A human crisis

While its universality is one defining trait of the coronavirus crisis, so is its human element. This didn’t start tied in the distant vagaries of credit default swaps, as did the 2008 global financial crisis. COVID-19 was – and is – in us. Ii is in our lungs. It makes us sick. It has killed friends and loved-ones, colleagues and strangers. This is a human catastrophe with personal effects.

Prof. Caren Scheepers, faculty at GIBS and clinical psychologist, urges business leaders to be alert to the fact that the coronavirus and ensuing lockdown induced a grief response. “This was radical, disruptive change,” she explains. “Forced change like this is experienced in the brain as pain. Many of us experienced – and continue to experience – the five stages of grief. Recall how we denied it would impact South Africa when reports first emerged out of China? Then there was anger when it did. Many have experienced depression, and we have seen how bargaining continues – at home, in business and in political realms. Some of us have reached acceptance, but we all experience the stages to different degrees and for different lengths of time.”

Try things, and do more of what seems to work.

Scheepers stresses the importance of leaders being cognisant that colleagues and employees are bringing a variety of emotional wounds back to work with them. “It starts with self-awareness,” she explains. “The worst outcome is a leader who projects her own stuff onto others. You’ve got to be in tune with yourself to be in tune with others. People want empathy for what they have been through. In particular, managers should be mindful of those who had personal issues before the crisis struck. But don’t try to be the counsellor. The manager’s role is structure and support. Make use of employee wellness programmes wherever you can.”

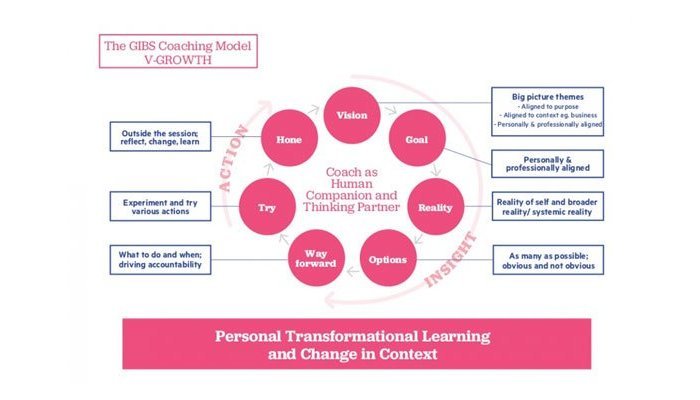

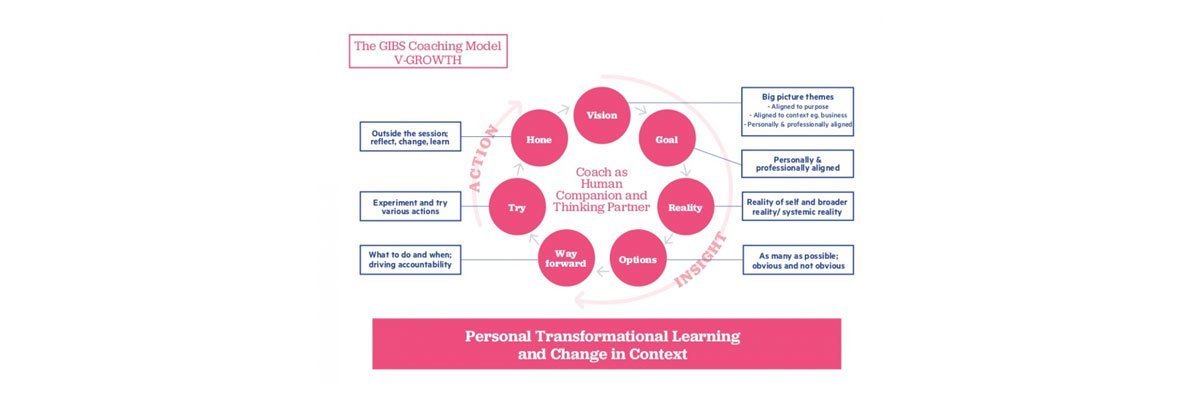

One business tool that expressly acknowledges our humanness as business leaders is coaching. To a person we feel not just the punches the coronavirus landed on our businesses, but the hit to our personal finances, the strain it put on our families and the anxiety we may try to keep private. All of this makes it especially hard to use the asset we need most at a time like this: our brains. “Even at the best of times, we fool ourselves,” explains Alison Reid, who runs Coaching@GIBS. “We convince ourselves that we are using conscious thought, when in reality we are driven largely by our unconscious.” That fosters inertia at a time when we need adaptation.

“A good coach asks the right questions,” Reid continues. “Being independent, they help shine a torch on new corners of the room where creativity lies. You can think with your Exco and colleagues, but the risk is that you all shine your torches on the same spot – that’s group think. A coach can also be a release valve. You are allowed to be anxious and overwhelmed in front of your coach, even if you don’t want to show weakness to anyone else.”

The manager’s role is structure and support.

Leading through storytelling is another powerful tool in the arsenal to address fears and hopes of followers through change. Whether consciously or not, even the clumsiest scribes and orators among us have a rich education in inspiring plots. This is part of the human experience of watching films and reading books that invoke the universal narrative arcs that grab our attention and make us feel and remember. If you’ve seen a James Bond film you know the ‘defeating a monster’ line; reading Beauty and the Beast demands an appreciation for the ‘rebirth’ arc; and anyone who cried during The Lion King (or pretended not to) gets the ‘voyage and return’. One additional outcome that business narratives need, but which artistic tales might not, is to prompt action.

Dave Beaty, adjunct faculty at GIBS and registered psychologist, teaches and consults on storytelling in business. He advocates three requirements for “stories, anecdotes and vignettes that are framed, crafted and communicated to followers in terms of ‘the war we need to fight to revive both ourselves and our company’.”

1. Get their attention. Begin the story by describing something negative. Use either personal or company anecdotes so that you relate to your listeners.

2. Describe how others overcame their obstacles.

3. Craft the story with a positive ending by describing the positive opportunist – i.e. the protagonist who emerged from crisis having overcome obstacles and achieved both personal and company successes that meant “winning the war”. Remember that negative stories get attention; positive stories inspire action.

Crisis as opportunity

While we’ll each need to tell and live our own stories, a number of strategies suggest themselves as likely chapters in the yet-to-be penned anthology of South African comeback tales.

Global supply chains were among the starkest victims of the crisis; decades of globalisation partially frozen in days. In February, the virus is thought to have cost US$50 billion in exports. As borders and shipping routes reopen, an opportunity exists for South African exporters as part of a strategy that those in the know are calling “China Plus”. In short, the unprecedented GDP boom and gargantuan efficiencies of Chinese manufacturing have left importers and exporters excessively reliant on this one trade partner. People want geographic diversity at not just a country level, but at a regional level. This makes for lucrative opportunities in finding new export destinations for South African goods.

...an opportunity exists for South African exporters...

Marianne Matthee, GIBS professor and international trade specialist, explains how we can now mine freely available UN data to find new, often unexpected, export destinations. “We can go into a great deal of detail on both products and places,” she says. “We look not only at market size and growth rate, but evaluate culture, market concentration and geographic elements. So, we can identify niche markets with potential.” This means we can find ‘unusual suspects’ that intuition misses.

Turmoil also represents a burning platform that can ignite the emergence of an entirely new category. Consider the category of online groceries. Since the mid-1990s, we’ve assumed we would soon have an efficient model for delivery of fresh groceries, and perhaps the demise of the traditional bricks-and-mortar store. Greg Fisher, GIBS adjunct faculty and professor of entrepreneurship at the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, studied this slow-burning failure to launch in real time, co-authoring the 2012 conference paper The Market that Wasn’t: The Non-emergence of the Online Grocery Category. “Despite huge amounts of venture capital, and three major companies emerging, the players couldn’t coalesce on what this new category of online groceries meant to the customer. Buyers didn’t have a clear picture in mind of what the value offering was.” It wasn’t until more recent moves from the likes of Amazon that the category finally emerged in the US.

Fisher explains how the South Africa of 2020 differs from the US experience: “Incumbents don’t need to convince consumers that a new way works. The coronavirus made it essential. So, the driving force is external. Several incumbents did the right thing, in my opinion. They acted fast. Those who have waited for a perfect app and a flawless delivery system may have lost out on a category that I think will stick.” The irresistible question is what other emergent categories has the COVID-19 crisis dislodged in South Africa?

A new normal

Skype was released in 2003, suggesting that we have been tinkering with a digital workplace for over 15 years. The coronavirus forced that to happen in three days. Meetings went onto Zoom, lectures beamed through cyberspace and even the most reluctant athletes among us turned spare bedrooms into online workout rooms.

GIBS professor of international business and human resources scholar, Albert Wöcke, calls the current milieu ‘workplace 3’. “In the late 1990s everyone wanted to move to a digital workforce, but there were issues of alienation and it just didn’t work,” he recalls. “Again, in the mid-2000s, there was another surge into virtual workspaces, but this was mainly multinationals trying to put global value chains together. Today, two important things are different: we have the technology and we have no other choice.”

Wöcke goes on to frame the trouble most of us are experiencing with working from home. “You have to ask what type of boundary an employee wants. A thick boundary would mean doing all their work in an office in their house and taking structured breaks to see their family. But some will want a permeable boundary, where the two blend more. In the latter case, you simply give the worker targets and outputs to achieve and they fit it in with the family. The key is for HR to understand and match employee and company expectations.”

The comeback will undoubtedly need the right corporate culture, but this is something we have always done together, in person, in teams. Again, Wöcke sees dramatic changes, including a greater need for people with the right soft skills: “People who can interact and manage and maintain a culture virtually without having to meet face-to-face. I predict more self-managed teams. Teams will be smaller. They will interact with other teams across the organisation to achieve an overall objective.”

Today, two important things are different: we have the technology and we have no other choice.

C is for comeback

Responding to questions raised by local businesses in his community in and around Bloomington, Indiana, at the Kelley School of Business, where Fisher is now professor of management and entrepreneurship, the GIBS alumnus drew on the business model canvas to sketch “eight critical things to consider and act upon if you want to give your business the best chance of surviving over the next 3 – 8 months months”.

The eight Cs

1 – Cash management

Carefully monitor and manage all cash coming in and going out. Think about sources of cash, like special grants and loans, and consider ways to generate cash from customers past, present and future.

2 – Customers

Customer needs have changed and will continue to do so. Some will no longer need your product, but some will need it more than ever. Home in on the latter. Determine what new needs your customers have which you can fulfil. Talk to them, if need be.

3 – Core competencies

Distil what you are really good at, and double down on these things. Apply them to any new customer needs you may have identified. This may give you a brand-new value proposition.

4 – Changing channels

If your usual channels for reaching customers have disappeared or become limited, look for alternative means. Are there channels you’ve never considered before? Can you deliver value online?

5 – Collaboration, not competition

In business we tend to talk about competitors and how we can beat them. In times like these, we need to break that mindset and think about who we can collaborate with in order to survive and create and deliver value. It may mean working with a competitor. Think about who you can partner with and how.

6 – Cutbacks

Strategy is often about what we decide not to do. Coming back from the crisis will enhance the importance of this. Are there activities you can cut back on in an ethical way? It may mean you can’t pay employees their full salaries but try to step up and not leave people without any income.

7 – Community help

Adopt a community mindset and think about how your business can help the community and how you can draw on your community for help.

8 – Communication

Communicate with all stakeholders. Let you customers know how you are adapting. Keep employees informed of your plan of action. Ensure investors know where you stand and what support you need. You may need to employ new communication channels.

Watch Prof. Fisher’s brief YouTube video where he elaborates on the eight Cs here

Branding your comeback

Former marketing lecturer at GIBS and now professor at the UCT GSB, Mignon Reyneke, who specialises in branding, outlines three potential ways consumers may respond during the comeback. “First, they may just race out and consume, but that seems unlikely given the financial constraints. Second, they may hang on to the habits we developed during lockdown. That would mean more shopping online, more time at home with family, and cooking ourselves. Finally, it could be a slow and cautious recovery where we are particularly careful about large gatherings for some time. I think the latter two scenarios will predominate, but it will vary by category.”

Reyneke flags three facets of consumer behaviour worth monitoring during the comeback:

1. Consumers will be very discerning. We will all be watching our finances. This matters for brands, because consumers become acutely aware of quality when they can’t afford to replace an item. They rely on brands they trust.

2. We will also appreciate brands that don’t just pay lip service to our needs as we all recover. We all received a thousand emails from every brand we’ve interacted with in the last decade saying, “we’re with you”. But are they really? I think we will increasingly appreciate brands that don’t just say it but do it. That matters when they are competing for share of significantly smaller wallets.

3. Finally, keep an eye out for unusual synergies. We are seeing all these creative partnerships like clothing brands with delivery systems partnering with farmers’ markets to deliver fresh produce.