As an engineer involved in the renewable energy space, I was concerned about the persuasive impact of fake news on the quality of decisions taken in climate change. Importantly, I was concerned about how we could overcome the proliferation of fake news, which was the driver behind the research for my doctoral thesis.

The proliferation of fake news in the climate change debate

Fake news is increasingly becoming a challenge. This is because the spread of information, which is possible to disseminate across a number of platforms, is increasing. The issue with fake news is that it is deceptive, offering up misleading information made more convincing because it is spread through channels that mimic legitimate news sources.

The role of fake news is to create a distorted perception of reality. And when it comes to the climate change debate, it depends on where their vested interests lie. One of the biggest concerns around fake news is that it can result in suboptimal decision making by individuals and society and that its presence can result in people questioning legitimate scientific evidence.

Fake news in climate change can be traced back to the early nineties, where the US-based Global Climate Coalition (GCC) became increasingly concerned with the growing body of scientific evidence pointing towards post-industrial human activity and the associated increase in carbon emissions as the leading cause of global warming and climate change.

The Global Climate Coalition (GCC) was formed to represent all industries that were totally reliant on coal and other fossil fuels, like oil and gas, and therefore had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo at the time. As such, much like South Africa’s Bell Pottinger case with the white monopoly capital narrative, the GCC hired a world-class public relations company to change the narrative.

What they found was that if they positioned their misinformation from a scientific perspective, by getting scientists to contradict the emerging evidence, they would have a significant impact in changing the dialogue. As such, they recruited scientists to assert that the science around the role of human activity, namely the burning of fossil fuels and the emitting of carbon dioxide within the climate change debate, is not conclusive and therefore cannot be attributed to these activities. Their aim was to create enough 'scientific' uncertainty to confuse people.

They were so successful in this campaign, that even with known environmental activist Al Gore in the White House, the US was not a signatory to the Kyoto protocol.

My research

I structured my research to understand whether we can change people’s perceptions once they have been exposed to 'convincing' fake news. I entitled my thesis Countering Fake News: A Longitudinal Experimental Examination of the Relative Influence of Source Bias and Social Consensus as Discounting Cues on Attitudes.

My research design was a full experimental research and design framework that used two pilot studies and a main study, which looked at the response from 190 participants. The study was conducted over three months in five parts, which were headed Time 1, Time 2, etc.

The first measure, at Time 1, was to establish a baseline to test participants' initial attitudes to climate change. Then at Time 2, I looked at what, if any, impact fake news had on their initial views. At Time 3, which was after the fake news story was read, I followed up with a contradiction to the fake news (called discounting cues), and finally, I looked at the impact that time had on people’s views. Time 4 was measured after two weeks while Time 5 was measured three months later.

Time 1

I started my research by sending people who had opted into my study a number of questions to test their views on climate change, global warming and carbon dioxide emissions. I asked them how much they agreed with the following statements on climate change:

- It is attributable to carbon dioxide emissions.

- Human activity is the cause of climate change.

- Human intervention is required to address climate change.

- There should be urgency to address climate change.

Time 2

Once I had that feedback, which gave me an indication of where their views stood before I started my study, I sent them a fake news article. The article I used was compiled by researchers and was a typical example of how climate change fake news is presented. I adapted the piece so that it had a South African focus, and I presented it as a blog article. The article stated a number of mistruths around climate change, including that human activity is not a contributor to climate change and that 31 000 scientists had signed a petition stating that climate change is not a reality.

After sending the article to my respondents, I asked questions to understand how much they had internalised the contents. I then measured how their attitudes had changed as a result of reading the blog. I found that the change in attitude after reading the fake news piece was statistically significant in terms of the influence it had on people’s view on climate change.

Time 3

It was at this point that I wanted to measure if this change of attitude was, in fact, reparable. So I split the respondents into three groups. The first group was the control group, who only saw the blog article.

The second group were exposed to reader comments, typical of those at the end of a blog article. The comments debunked the findings in the blog. In the comments, I had six convincing arguments questioning the contents of the piece, and calling it fake news. I wanted to see if you could impact readers’ attitudes by showing them that the information was questionable and stating that the blog was fake news.

The third group of people were told that that the author of the article was not credible and was biased as he had a vested interest in the fossil fuel industry and was spreading fake news to intentionally confuse the climate change debate. It did not comment on the content of the piece. This information was given in the form of letters to the editor, saying that the writer was concerned that a reputable publication would publish an article like this without checking or verifying its sources. In the letter, I highlighted that the author of the blog has shares in a mine and was a member of the Global Climate Coalition.

Time 4 and Time 5

Then finally, I wanted to measure if attitudes that were swayed with the fake news would change over time or if they are durable. I also wanted to see what information stuck in readers’ memories – the fake news, the letters to the editor or the comments at the bottom of the article. To do this, I measured the attitudes of all three groups after two weeks and then again after three months of the initial reading of the piece, the comments and the letter to the editor.

Findings

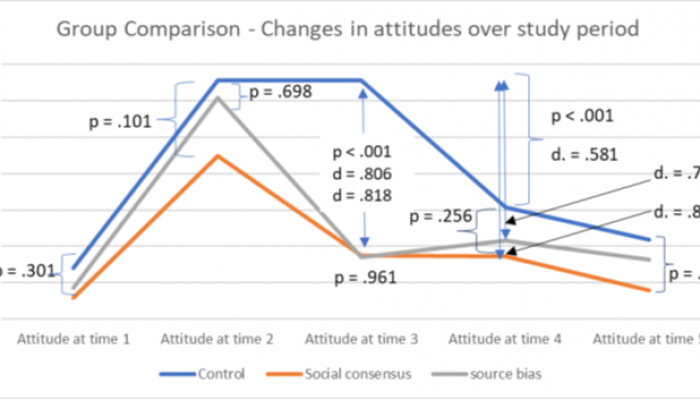

The findings were very interesting. Looking at the graph, you will see that the initially all groups held similar views on climate change at the start of the study.

The impact of fake news article affected how people viewed the climate change debate and was statistically significant.

What was really interesting to me was that both group 2 and group 3 responded in the same way to the corrected information. My research found that the impact of the comments and the letter to the editor, questioning the validity of the piece, was statistically identical. Both discounting cues, the comments at the bottom of the blog and the letter to the editor, were equally effective in changing people’s attitudes and countering fake news, and the change in their attitudes was significant.

At Time 4, two weeks after the group was exposed to the fake news, everyone’s attitudes, including those of the control group, started to return towards their original point of view. By Time 5 on the graph, which was three months later, there was an incremental shift in people’s attitudes, towards the position put forward in the fake news article, but the difference across the three groups were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Research into countering fake news is new, however, the peddling of fake news is not. The persuasive effect of fake news was confirmed when participants exposed to fake news had a statistically significant shift in attitude. The two discounting cues proved equally effective in restoring attitudes. With time, attitudes had migrated towards their original values, but the incremental shift in attitudes suggests the presence of the continued influence effect, meaning fake news does leave an imprint, albeit small, in people’s thinking.

The results from this research have practical implications for a number of spheres of persuasion, where the issue of fake news has become prevalent, including environmental and climate issues, politics, and the tobacco, sugar and asbestos industries.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Fake news is a reality that can mislead and distort people’s perceptions around major global issues.

- Fake news is disseminated by organisations that have a vested interest in distorting the debate around critical issues like climate change.

- People are open to accepting an alternative point of view if it is presented in a legitimate way.

- Understanding how to negate the effects of fake news can have major implications for any industry that is being targeted by lobby groups with a specific agenda, from the smoking, sugar and asbestos industries to politics and climate change.

Dr. Vikesh Rajpaul was instrumental in the establishment of the renewables unit in Eskom, and is currently a senior manager in Eskom, with end-to-end accountability for all large-scale renewables initiatives in Eskom, including responsibility for compiling and driving Eskom’s renewables strategy. He is a hands-on mechanical engineer with professional Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA) registration, has an MBA and a Government Certificate of Competency (GCC).