And it’s not just musicians who have suffered – museums, theatres, festivals, cinemas, and galleries have shut their doors, putting millions of jobs at risk globally.

Culturally insensitive

The cultural and creative industries’ contribution to the local economy in 2018 was R74.39 billion, equivalent to 1.7% of South Africa’s GDP, according to a 2020 study by the South African Cultural Observatory. Yet, the Covid-19 relief efforts for this sector have arguably been sparse.

In February 2021, artists staged a three-week sit-in at the National Arts Council (NAC) offices, demanding answers regarding mismanagement of the R300-million Presidential Employment Stimulus Programme funds the NAC was tasked with disbursing to the sector. Eventually, Nathi Mthethwa, the minister of sports, arts and culture, announced that there would be a forensic investigation into the matter. This, however, did little to help the 600 funding applicants who had contracts signed and approved by the NAC, which the council reneged on after approving 1,374 applications and then announcing it could not fund them all.

Many venues and organisations have not been able to recover from the effects of the pandemic. For example, Cape Town’s beloved Fugard Theatre announced it had closed its doors for good on 16 March 2021. Writing about its closure, Fiona Ramsay, a performing arts lecturer in performance and voice and PhD candidate, University of the Witwatersrand, said, “The growing crisis in the performing arts sector has been caused by the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture’s lack of vision and strategy and minimal understanding about the sector; and hence the artist relief fund offers little hope for the rebirth of an industry after the lockdown.”

Despite the challenges, some performers, artists and organisations have managed to keep their heads above water by reinventing themselves and finding new ways to practise.

Creating new channels

“Around the world, online platforms to showcase art had quickly developed or expanded (think virtual galleries). So where before lockdown, art lovers would physically visit their favourite three or four galleries from time to time, now the whole world was available to browse through at leisure,” says Mirna Wessels, CEO of Spier Arts Trust.

“One of the most important aspects of Spier Arts Trust is that we are closely connected to many artists’ careers through long-term relationships. Without being able to visit artist studios and exhibitions, it has been much more difficult to stay up to speed with what everyone is doing,” Wessels admits. “Thankfully, we were able to continue with the Creative Block programme, though in a different guise. All our feedback sessions are now held online through Zoom hand-in sessions, and artists deliver accepted work to centres around the country. In this way, we are able to work directly with about 80 artists in a three-month span. However, while we have been able to continue with the programme, there are definitely some artists that have unfortunately not had access to data or a computer to make use of it.”

She says there has been a rise in independent exhibition spaces managed by artists themselves. “I am not sure that this is a long-term trend nor if it will be beneficial to artists in the long run, but certainly it gives an intimate and personal dimension to the experience of art,” she says. “Every physical arts engagement currently feels like a gift – perhaps that’s a bit dramatic, but that is my personal experience anyway.”

In the mix

David Alexander, the founder of Sheer Publishing and chair of the Music Publishing Association of South Africa (MPA-SA), says Covid-19 has also been a very mixed bag for the local music industry.

The MPA-SA aims to safeguard and protect music publishers as a collective, actively engaging with collection societies, government and content users to ensure artists receive adequate compensation for their works. “We represent about 95% of the music that is played at any point in South Africa,” explains Alexander. “We wanted to be more proactive about working with the collective management organisations to reduce their costs and increase their revenue and to assist with Covid-19 relief.”

Under lockdown, airlines, casinos, hotels and restaurants, did not trade. Pre-Covid, this pool of licensing contributed more than 20% of SAMRO’s collections. Furthermore, advertising on radio and television, which directly contributes to songwriters’ income, fell by roughly 20% over the past business year. While increased online activity has meant increased digital music income, Alexander says that streaming services are still only available to those with broadband and electricity. As a result, access remains a challenge in South Africa.

He’s also concerned about job-shedding. “When people are forced out of cultural industries, it’s not just an economic impact. There’s a cultural impact, too. Songwriters are the storytellers of what's happening to us now. We're going to have fewer people employed in the cultural industry, and therefore there will be less that is recorded about what we went through over this period. That's a pretty sad thing to contemplate.”

At the beginning of lockdown, the MPA-SA wrote to Mthethwa requesting urgent assistance for the music publishing and songwriter community. To date, it remains unanswered. Alexander laments the minister’s lack of empathy and says the value of creative and cultural industries as a driver of GDP remains underappreciated in South Africa.

The MPA-SA aims to create a research project that demonstrates the impact of this industry on overall African GDP. “We need to know the number of people who work in this industry and the value that their output achieves on the open market. The creative industries are a huge driver of GDP in many developed markets. We have the potential in South Africa to nurture an industry that is made up of young creatives, as long as we get the buy-in from government that music is a huge export opportunity.”

Holding the stage

Tarryn Steyn, an actor and singer based in the Western Cape, and host of the podcast, I hope I get it, did not benefit from local relief measures, despite being eligible and applying for various programmes.

“The only relief measure I benefited from was the Netflix film industry relief grant,” she says. “I won’t speak for anyone else, but I certainly felt that more could have been to support all artists. Without art, no one would have gotten through this lockdown. People -watched series and films and streamed new music. That is all art. I felt more relief could have been made available to everyone in the industry, not just a select few. I felt that our communities, our audiences could have supported our online endeavours more.”

She says the film and theatre industry came to a complete standstill as theatres and even film sets were closed. “Not only were actors left without work, but our crews, our front of house teams, our backstage teams – an entire industry decimated in the space of months. When the first few cases started to show up in South Africa, I was working on a TV series,” she recalls. “We implemented all necessary Covid-19 protocols, but ultimately we were forced to shut down the project. Theatre shows we had booked and were preparing to start rehearsing for were cancelled, and we had no idea when or if they would happen. It was incredibly difficult as an artist to navigate that time. That’s how my podcast was born. I was desperate to find a way to stay creative, stay connected to my colleagues, and the arts in any way I could. So, I established a production company and created the podcast, which has been my saving grace and kept me busy and connected to fellow creatives worldwide.”

Steyn says that artists are resilient, and the pandemic has demonstrated this. “Virtual online plays and musicals became the new normal,” she says. “I was able to perform in a play festival with people in America, be part of various play readings and audition for online musicals without leaving the house. These innovative ideas kept me sane and connected to my craft at a time when I desperately needed it. When restrictions were lifted, I was able to star in a short film with a skeleton crew and only two actors, and then I was able to film a play that streamed online. We were able to go back into a studio and do voiceover work. Slowly but surely, our film industry has started up again.”

Necessity is the mother of reinvention

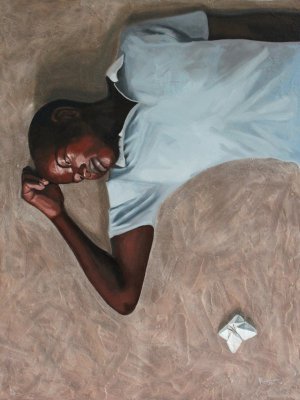

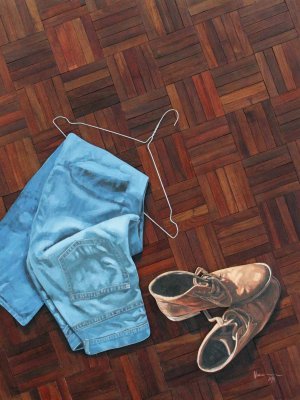

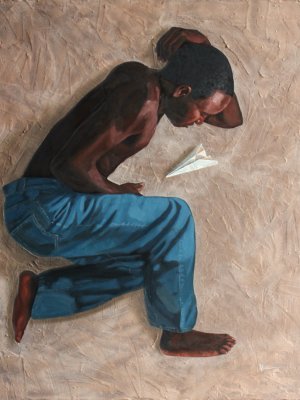

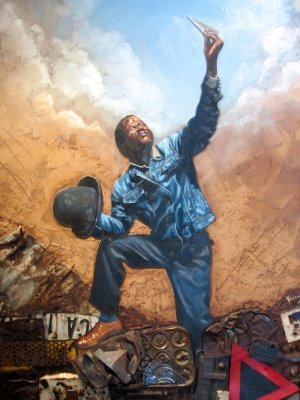

Visual artist, Vivien Kohler, received support from Spier Arts Trust and government Covid-19 relief efforts, allowing him to continue to work as a full-time artist.

“The pandemic affected us as artists emotionally; it affected us in terms of our future prospects; it affected us relationally, and it definitely affected us financially,” he says. “As an artist with a family, this became all too real to me in terms of needing to provide. I absolutely had to reconceptualise my practice in order for it to continue to be sustainable. I had to revert to working from home again. That was the easy part as the lockdown and isolation were mandatory. The difficult part was to ‘reinvent’ my work. This is where the Spier Arts Trust and its Creative Block initiative played a most valuable role. It allowed me space to try something relatively new in my practice and redirect my path toward sustainability and provision. It actually took my practice to a better place and opened up way more doors than imagined. As an artist, most of my working time is spent in isolation inside of my studio. The pandemic and its lockdown, as horrific and trying as it was/is, had its own silver lining in that it forced me to deal directly with the future of my career.”

How to help

- Choose to personally support South African artists through attending shows (even if it’s online), buying local art, and consciously consuming more local content.

- Contribute towards artist relief funds, such as The Lockdown Collection.

- Support non-profit organisations in the South African arts ecosystem, such as:

- Consider corporate arts investment through supporting educational programmes for youth, collecting artists’ work, or giving artists platforms for exposure.