There’s a quote in the family ranching TV drama Yellowstone in which an old cow hand, Lloyd, tells his young boss, “Different never works.”

While that fits the neo-western wrangler storyline, the scientists and planet-watchers at Nasa are advocating a different approach. The agency warns that the impacts of changing rainfall patterns, higher temperatures, and greenhouse gas emissions due to climate change will start hurting maize yields as soon as 2030. Based on 2021 crop modelling, NASA climate scientists have seen a large, negative and "fundamental shift" from their 2014 projections. This will have serious worldwide implications.

It isn’t just Nasa that’s concerned. Researchers in Nigeria, such as Isaac Ayo Oluwatimilehin and Ayasina Ayanlade, say Africa’s rain-fed agricultural model is a major risk, given changing temperatures and rainfall patterns. They note that “climate change may lead to about [an] 80% change in the yield of crops in the region”. Oluwatimilehin and Ayanlade believe adaption methods are vital, from the crops being produced to planting times and methods, as well as policy support and, of course, the use of innovative technologies. Failure to do so effectively at a continent-wide level could impact Africa’s food security.

Closer to home, Professor Laura Pereira from the Global Change Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand and Stockholm University’s Stockholm Resilience Centre in Sweden has been researching multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder agriculture futures across Africa for more than a decade. She is acutely aware that many of the issues raised in leading global journals remain unaddressed in spite of the climate change clock ticking. “We said this in 2017 and we are still saying it in 2025,” she says.

Stellenbosch University’s Professor Guy Midgley underscored this view in March when he told SABC News, “We are in an age of consequence of a lack of action on climate change since the 1980s… Governments have not stepped up to the plate, including in some ways South Africa, although we argue for our development space – but it comes at a cost.”

What’s being done?

Certainly the South African agricultural sector does not appear to have been sitting on its hands. A 2021 survey by the Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators at the Human Sciences Research Council showed vibrant innovation within the country’s agribusiness sector, where better and more modern processes were being implemented and products, services, and farming plans aligned to increase productivity and competitiveness. Of the businesses polled, 67.1% were engaged in innovation activities, rising to 72.9% for medium-sized agribusinesses. Farmers engaged in agribusiness innovation were particularly focused on training, machinery and equipment options, and using appropriate computer software.

Since then, artificial intelligence has bounded onto the scene, bringing with it advanced weather predictions, real-time crop monitoring, and pest control solutions, and even the promise of self-driving machines.

Pereira agrees that significant innovation is taking place in the agricultural sector, although she argues that much of it focuses on industrial production and conservation agriculture, rather than sustainable approaches like agro-ecology, which takes a more systemic view of the agriculture system.

“Mexico – the home of maize – is going into indigenous [foods] and varietals, recognising the importance of this rather than the focus on genetic modification (GM) and all the problems that come with that, from an intellectual property perspective, for instance,” says Pereira. Mexico’s approach respects indigenous knowledge, crops, and traditional ways of cooking and growing food in an agro-ecological way, where companionable crops are planted together. “Agro-ecology could feed the world, if you got rid of the waste and the other aspects that our current industrialised system enforces on us,” believes Pereira.

It is for this reason that Pereira advocates involving more systemic thinkers in this conversation.

While provinces like the Western Cape are starting to question the production of crops not ideally suited to the local rainfall system, having a broader conversation about crop alternatives isn’t really gaining traction. Instead, researchers such as Klara Fischer from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences argue that by going down the GM maize route – and banking on the potential for gene-editing to shore up yields – South Africa is disadvantaging smaller players who cannot afford costly GM seed.

From an equity perspective this is a concern, agrees Pereira, who fears that “we are so locked in the existing system that it’s hard to budge”.

The rock and the hard place

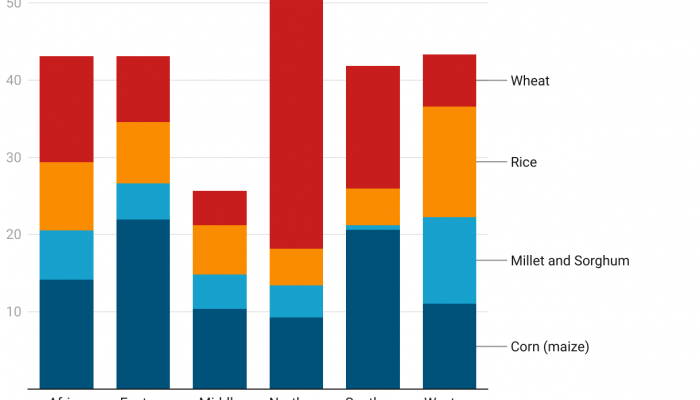

In part, this has to do with the fact that research into agricultural systems like South Africa’s are locked in a CGIAR (the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research) system mindset. This global research body focuses on transforming food, land, and water systems to cope with the unfolding climate crisis, but Pereira notes that the entire approach is orientated around productivity, yield gaps, and the world’s leading crops, like maize, wheat, and rice. This sidelines neglected or underutilised species that could be potential drought-resistant options, rather than perpetuating the “colonial legacy” crops which are today’s staple foodstuffs.

The only time these established systems are disrupted is when a popular new superfood hits the shelves and spikes the production of crops such as quinoa, blueberries, or goji berries. However, the foods are usually earmarked for export or high-end consumers, driving up pricing and putting these products out of reach for the average household.

There are also consumer tastes to consider. “You’re not going to change South Africans’ cultural preference for pap overnight,” admits Pereira. “But you can, from a cultural perspective, go back and tell people about a product like sorghum. Make it sexy, make it trendy, and make it something that people want.”

Sorghum is just one of the staple foods that could fit the gap left by a continued decline in maize yields. Cassava is another. However, “reconfiguring an entire apparatus that has been configured in a particular area” or towards a specific crop such as maize is a challenge, says Pereira.

This is made more complex if producers, retailers and marketers don’t invest time and money into changing local tastes. This was certainly the case with cassava, says Pereira, explaining that the pro-cassava lobby completely “missed the whole taking it to market thing”. When it came to the crunch, consumers just didn’t want to eat cassava bread.

But in the near future, options like cassava bread might become more appealing.

Cassava root, which is endemic to South America, has “low input requirements, tolerance to drought, the ability to grow in marginal soils, and long-term storability of the roots in the ground, [which] makes cassava a resilient crop for food and nutritional security”, a group of South African researchers wrote in 2021. The crop also has potential industrial applications across livestock feed and pharmaceuticals to biofuels and alcohol production.

Commercial farmers are growing cassava in Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and KwaZulu-Natal, and in 2023 South Africa exported $8.24 million in cassava to markets such as the Netherlands, the UK, and Portugal. Conversely we imported cassava to the value of $401 000 in the same year, from growers in Zambia, Egypt, Malawi, and China.

So, maybe it’s not just about the maize. Maybe shifting agricultural systems starts with making alternative food choices palatable to consumers, and hoping that in this case "different" sticks.

Let’s talk solutions

Looking at the issue of food systems, crop choices, and the future of agriculture in South Africa through a business management lens requires some serious horizon scanning if you want to even consider “nudging the system”, believes Professor Laura Pereira.

While it’s easy to focus on a single issue in the complex, intertwined food system, Pereira warns against only considering the impact of climate. There are any number of other, equally significant drivers, such as equity, cultural acceptability, nutritional values, and export markets. “It’s not just climate affecting rainfall, therefore we can’t grow maize,” she says. “There’s a whole broader system behind it.”

Pereira believes that business needs to start thinking seriously about the way it innovates, and “thinking through the lock-ins we need to break within the current system of innovation, within the current marketing of the foods we eat, and how can we break that down while also supporting things that are happening on the ground and that do actually meet these different principles of sustainability, climate resilience, adaptation, equity, and livelihoods.”

Woolworths’ regenerative Farming for the Future approach is a step in the right direction, although Pereira notes that something more widespread, equitable and sustainable is required in the long run. Conversely, there must be better communication and cooperation between market players and farmers to identify new tastes and preferences. The case of Wellness Warehouse stocking Indian sorghum flour (jowar flour) when sorghum is grown in South Africa and costs less in supermarkets, is the sort of disconnect that needs attention.

Globally, Pereira points to countries like Brazil which produces swaths of agricultural research. “In the state of Pará, in particular, they are looking at creating economic opportunities from keeping the Amazon intact,” she explains. It is hoped this so-called forest economy will not only stop deforestation but see some 24 million hectares of forest restored while creating more jobs and increasing GDP. Innovations being applied in Brazil include investments into the bio economy, strategic land use, and prioritising low-carbon practices such as agroforestry, composting, and genetic enhancement.

Did you know?

If you have any doubts about the current shifts in global food production then consider this:

- In the hot, dry Northern Cape, the Karsten Group is operating a date orchard along the Orange River between South Africa and Namibia.

- Cactus pear farming is being explored in the Puglia region of southern Italy. The plant is fast growing, climate resistant and has applications for livestock feed and as a biofuel source.

- The UK is now producing well-regarded wines as far north as Scotland. The number of vineyards in the country has tripled over two decades.

- Kiwi fruit are now being exported by New Zealand-headquartered Zespri International, the biggest marketer of the fruit, from orchards in the northern hemisphere including Japan, France, and Italy.

- Japan’s Wismettac Group is looking to South Africa as a likely location from which to cultivate the sweet Japanese-bred Kimito apple, renowned for its long shelf life. The move would enable Japanese consumers to enjoy the apple year-round.