Platinum group metals (PGMs) are South Africa’s biggest export. More than 80% of the world’s platinum comes from South Africa, and around 30% of palladium stocks. PGMs were also the biggest drag on the mining and quarrying sector in the first quarter of 2025, which was down 4.1% overall for a negative 0.2% contribution to GDP.

However, that’s not the full story. As Tana Mongwe, head of responsible investment research at Old Mutual Investment Group, points out, the PGM sector is also the biggest employer among South African mining companies. PGMs account for more than 181 000 direct jobs, and support countless businesses along its value chain, from processing and logistics to the many local retailers, hairdressers, and taverns that service South Africa’s mining towns.

“What happens to the PGM sector matters to South Africa at a grassroots societal level,” says Mongwe.

So, in the first half of 2025, when platinum prices started trading at highs last seen in 2014, this was good news for South Africa miners such as Impala Platinum, Sibanye Stillwater and Northam Platinum. “Little silver” broke through its usual $900-to-$1 100-an-ounce range to pass $1 400/oz in early September 2025.

The principal driver of this shift was supply. Or, rather, the lack thereof.

A structural deficit

Despite projections pointing to a PGM sector in decline, this pricing uptick is reflective of a growing supply/demand issue.

The World Platinum Investment Council’s director of research, Edward Sterck, notes that PGMs will see a supply deficit of 966 000 ounces in 2025. That’s slightly more than the 992 000-ounce deficit in 2024 and the 896 000 ounces recorded in 2023. This trend is projected to continue until 2029.

In short, says Mongwe, “We are going to hit a supply cliff.”

There are two structural reasons for this. In South Africa – which has about 70% of the world’s known PGM reserves – miners have not been investing in new production. PGMs are expensive to mine, with the company International Precious Metals putting production costs at around $1 800/oz compared to $957/oz for gold. With prices underperforming and long-term projections pointing to a steady decline due to the impact of electric vehicles (EVs), this dampens the appetite for heavy capital investments.

As Northam Platinum CEO Paul Dunne told Reuters in 2024, the choice to underinvest will have profound implications for the future. “We haven’t replaced that asset base and the asset base is a depleting asset; all mines are depleting assets from day one. This will exacerbate the natural depletion of South Africa’s ageing shafts,” said Dunne.

This depletion is already evident in the overall PGM output from South Africa dropping to 3.9 million oz in 2024 from 5.3 million oz in 2006.

Dunne – who told Miningmx in 2025 that “the market will turn” – is one of the PGM miners still investing in new production, in the hopes of a long-term payoff. “That is the nature of mining,” he told mining journalist David McKay. “Upfront capital, long lead times, and hard slog before you get the return.”

The second structural challenge is tied up with South Africa’s precarious national grid and the peak of the load-shedding crisis, which hit between 2022 and 2024. Electricity constraints disrupted mining operations, resulting in scaled-back operations, equipment failures and, in some cases the early mothballing of shafts. While things have settled with the re-commissioning of three coal power stations and renewables coming on line, balancing the grid remains a challenge. In fact, a new report by Cresco and Standard Bank Corporate & Investment Banking notes that ageing coal-fired infrastructure could force another power supply crisis as early as 2030, unless government acts swiftly to add new generation and transmission infrastructure.

Then there’s the issue of EVs.

The elephant in the room

As Mongwe explains, until recently the accepted view was that an EV future boded ill for PGMs. After all, “the automotive sector makes up about 60% of global PGM demand, so this decline in demand would be game-changing”.

For this to happen, however, certain targets would need to be met. For instance, “If China was to achieve 60% new EV penetration by 2030, as planned, and Europe saw 100% battery EV penetration by 2035, sometime around 2034 EVs would overtake internal combustion engine technology, firmly establishing electric as the dominant technology,” says Mongwe. “In the process, this would cause PGM demand to steadily fall by around 5% year-on-year per annum to 2035.”

This view hinged on a runaway transition from internal combustion vehicles to EVs. Instead, it has become increasingly apparent that – for now, at least – consumers are choosing hybrid options. This tweaks the forecast for PGMs. Instead of being cut out of the automotive supply chain entirely – as the need for catalytic converters (of which PGMs are a key component) rapidly declines – hybrid vehicles still require this pollution-mitigating technology.

Bearing in mind that the EV sector itself is extremely fluid at present, with China’s excess capacity stemming from heavy government support and resulting in a bevy of new marques on that market, there is considerable manoeuvring behind the scenes. Trade tariffs and incentives are also in play, as is government policy and, of course, consumer preferences.

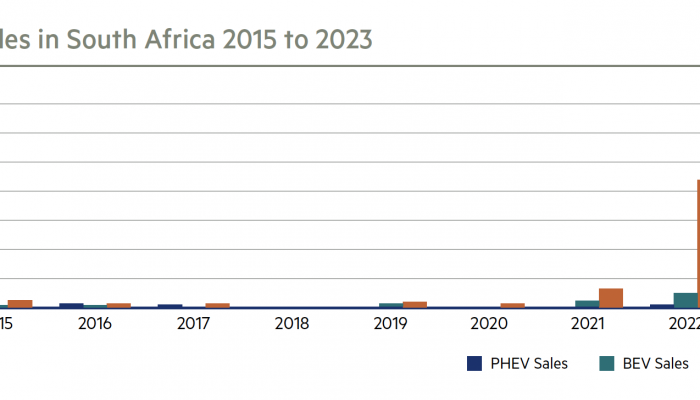

According to Reuters, quoting the Rho Motion consultancy, sales of fully electric vehicles slowed to 11% year-on-year in the first half of 2024. This despite the fact that China surpassed one million EV unit sales in a single month in 2025. At the same time, hybrid sales swelled by 44%. So, while the writing is on the wall for the traditional internal combustion engine, it seems consumers are handing PGMs a lifeline.

Price has a lot to do with this, as do concerns around driving range, EV charging times and EV charging infrastructure.

Unpacking the puzzle

“It’s becoming increasingly evident that, outside of China, EVs are simply too expensive,” says Mongwe. “In regions like the European Union and the United States, EVs cost 20%-60% more than the cost of a comparable internal combustion vehicle.”

Then there’s import duty to consider. Speaking to Iman Rappetti on Investec Focus Radio in 2024, the then co-CEO of Mercedes-Benz South Africa, Mark Raine, noted that “the import tax on EVs is 25% against internal combustion engine vehicles that is at 18%. And then in addition to that, for vehicles over R700 000, there’s an additional ad valorem tax of 17% and above”.

During the same podcast, Ndia Magadagera, CEO of EV charging infrastructure firm Everlectric, singled out countries such as Norway and the UK, which are successfully supporting mass adoption through user incentives and policy support. Of all new cars sold in the Nordic country last year, 88.9% were EVs – a rise from 82.4% in 2023, according to figures from the country’s road federation. In January 2025, 95.8% of new passenger cars registered in Norway were EVs.

As both Magadagera and Mongwe observe, without meaningful financial incentives to entice consumers to buy EVs, it is unlikely South Africa will achieve this sort of uptake in such a short period of time.

Norway, of course, has the resources to sweeten the deal for consumers, which it has done consistently since 1990 when it first slashed import taxes on EVs and, in 1996, when road tax was eliminated for EV drivers. The country subsequently introduced free parking for EVs and exempted drivers from toll road fees. Heavy investment has been made in fast EV charging stations, powered by a national grid that generates about 90% of its power from hydroelectric sources.

In the absence of these interventions locally, South Africans are following the global trend and opting for more affordable hybrids – and inadvertently supporting the country’s PGM industry in the process.

The writing is not on the wall

Despite some heady shifts, which are impacting the very industry that was supposed to spell the end of PGM demand, the situation is far from clear-cut. This volatility makes it challenging to categorically define the timeline and trajectory of EV adoption, but it does appear that the transition for the PGM sector is being softened.

According to Mongwe, “A more realistic outlook is where, by 2035, EV penetration rates are closer to 40% with demand being driven largely out of China. This would mean a decline in PGM demand of 1%, rather than 5%, which challenges the view of a sunset sector.”

What the industry – and government – makes of this get-out-of-jail-for-now card will be the ultimate test. Broadening the net of potential customers offers some interesting options, such as jewellery manufacturing, which is currently turning to platinum as an alternative to pricy gold. PGMs have also long been a key component in medical devices such as pacemakers, while new uses are emerging in the food preservation space and, in the case of ruthenium, in the manufacture of advanced semiconductors for memory chips.

What is missing right now, believes Mongwe, is a clear plan of action to reset and stabilise the sector.

Only recently, South Africa announced a 150% tax incentive for local and international car manufacturers making new EV and hydrogen production investments in the country. The incentive, which will run for 10 years from March 2026, demonstrates that policy can be deployed to boost critical national industries in line with changing global export needs. The automotive sector employs around 116 000 people and, like mining, supports hundreds of thousands of associated jobs.

In much the same way, “we need to consider that PGMs and mining are extremely important,” says Mongwe. “We need to think about how the mining sector can continue to be sustainable, well into the future.”

Here’s what you need to know

- The global automotive industry’s move to electric vehicles was supposed to be the death knell for the platinum group metals industry.

- Some 60% of PGM output is gobbled up by the automotive sector.

- Without the need for catalytic converters, PGM demand was projected to fall by 5% year on year to 2035.

- Yet, with EVs still finding themselves – and consumers showing a preference for hybrid vehicles – PGM prices are rising in 2025.

- The challenge is supply.