One hears a lot about manufacturing’s potential for reinvigorating and expanding our economy – especially when it comes to the all-important issue of creating jobs. But the manufacturing economy is a complex machine with many moving parts, and gaining a clear picture isn’t necessarily that easy.

Professor Robert Lawrence, who visited South Africa in March under the auspices of the Centre for Development and Enterprise, argues that we must recognise that the percentage of the workforce globally in the manufacturing sector has been on the decline since the 1960s at least.1 This decline is caused primarily by increased labour productivity combined with the ongoing development of manufacturing technologies.

It is essential to note also that increased productivity is not evenly spread – much of the productivity gains are in manufacturing and agriculture because they can scale. Not good news for our president and his merry men who seem to be betting the farm, quite literally, on agriculture’s presumed ability to provide lots of jobs. By contrast, service industries are much less susceptible to productivity increases. The work done by plumbers, teachers, barbers, electricians, restaurateurs, nurses and so on simply cannot be scaled to the same extent, if at all.

(One of the best of that rare species, an economist’s joke, is William Baumol’s observation that it takes as many musicians to play Beethoven’s Fifth today as it did when he wrote the piece.)

Here’s the kicker: the demand for goods is relatively inelastic. That means that even as manufacturing or agricultural output rises and costs decline, consumption of those goods does not rise to the same extent. Professor Lawrence calculates that for each 1% decrease in price, consumption of the good goes up only by 0.7% – thus as more goods are sold, the value decreases.

Fewer jobs, more money

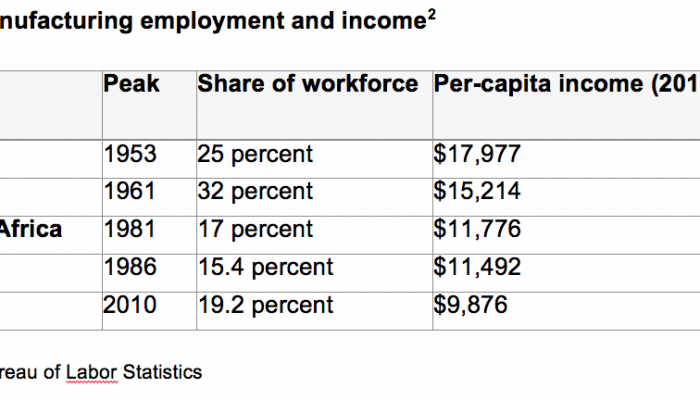

The ineluctable truth is that as manufacturing productivity increases, those working in manufacturing find their incomes rising – but there are fewer of them. The data also shows that over time, as countries hit “peak manufacturing”, the percentage of the workforce employed in manufacturing tends to reduce, as does its per capita income. Table 1 shows this clearly.

Manufacturing employment and income2

Across the developed world, manufacturing’s share of the total workforce fell from the 22%-37% range in 1973 to 9%-21% in 2010.3 In South Africa, manufacturing employed 1.181 million people in 2017, a decline of 23% since 1990.4

By contrast, as economies grow and incomes rise, people consume more services once they have enough goods. More and more people move from making or growing things to providing services. This trend will only be exacerbated by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which will see much more work taken over by machines of one sort or another.

Digitisation, artificial intelligence, robotic and 3-D printing may eviscerate manufacturing further but as Professor Lawrence notes, new jobs will be created in other areas. There are hundreds of millions more people in employment today than there were in the 1810s, he notes, and while it is possible the Fourth Industrial Revolution could change this pattern, “…to date, the productivity and employment data do not appear to support the conclusions of the pessimists.”5

Putting South Africa to work

Where does all of this leave South Africa? In line with so much else going on in our body politic and economic, not looking too rosy – but not altogether hopeless. Professor Lawrence’s analysis shows that, at best, we could not look for more than a relatively small percentage of the population employed in manufacturing, probably rather less than the 17% we achieved in 1981, as shown in Table 1 above.

But anything more than the abysmal current 2% (1.181 million) employed in manufacturing would be worth having. As Philippa Rodseth, Executive Director at The Manufacturing Circle argues, “Manufacturing is the engine of growth.” Not only do manufacturing jobs pay well, they have a multiplier effect because goods spark the need for services – first to transport, store and market them, and then to complement them, not forgetting the needs of the salary-earners for a growing range of services. As a result, there is a strong correlation between manufacturing and GDP.

According to the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, every dollar in sales of manufactured goods supports $1.33 in output from other sectors, the highest multiplier of any sector.6

Growing our manufacturing sector faces huge challenges. Ian Cruickshanks, Chief Economist at the South African Institute of Race Relations, is blunt: manufacturing’s contribution to GDP has steadily declined from 18.1% in 1951 to 13.2% in 2015.7 “There’s no reason to believe this will change,” he says, adding that whereas South Africa used to be able to count on inflows of foreign capital in the R60-80 billion range, this year has seen massive outflows – R44.8 billion (net) had left the country by the end of August, with August alone accounting for R20.7 billion.8

Growth, already low, seems to be actually falling as the severe contraction in the first quarter of 2018 shows, and could even drop below 1%; population growth, however, continues to rise.

“The country is getting poorer, and that means the government will increasingly struggle to fund the budget let alone the current account deficit, especially given the downgrade in our rating,” he says.

To turn this picture on its head will require three basic conditions to be in place: investors will need to be sure their assets are secure; there needs to be a constant, reliable and cost-effective energy supply; and labour needs to accept that reward and productivity are linked.

At present, all are lacking and the ANC’s policy trajectory looks set to actually worsen them.

GIBS’ Professor Adrian Saville concurs broadly that these basic conditions need to be met. “We need to partner with international investors if we are to rebuild our manufacturing sector,” he says. Currently, however, even local investors are declining to invest in major new projects, and the picture is one of cost-cutting and maintenance, with new projects being minor, according to Ms. Rodseth.

Competing with the world’s best

One of the challenges of manufacturing is the ongoing process of globalisation, which means that manufacturers face much more competition in both local and foreign markets. South Africa is far from most of the biggest markets in Europe, North America and Asia so in order to compete, we have to offset high transport costs.

Perhaps a more serious problem is that of scale. Manufacturing success is pre-eminently linked to scale and thus the ability to reduce the cost per unit. Achieving scale is hugely aided if there is a strong domestic market in which local manufacturers at least start in pole position, and which allows them to weather the inevitable fluctuations of international markets. Arguably, a large part of the United States’ continued economic success is the fact that its huge domestic market helps US companies attain scale, and ride out international business cycles.

Because of its low growth and poorly conceived government policies, South Africa is caught in a double bind. “There just is no real domestic market,” says Eric Bruggeman, Chairman of the South African Capital Equipment Export Council (SACEEC). He believes this could be changed if a sensible localisation policy was initiated. He cites PRASA’s infamous purchase of rolling stock as a prime example of capital goods that could have been produced locally.

Professor Lawrence also broadly supports localisation as a policy provided its costs are well understood. His suggestion would be for public agencies to be compelled to buy local provided the goods are within say 10%-15% of the cost of the imported equivalents.

Even if we could begin to create some local demand to kick-start local manufacturing, we would also have to confront the perennial South African question of skills. Our workforce is relatively unskilled and heavily unionised – there is great resistance to the idea of linking wages to productivity, one of the preconditions for success noted by Mr Cruickshanks. This intransigent attitude can surely be traced back to the ANC’s characterisation of South Africa as an internally colonised country (colonialism of a special type), which in turn creates a predisposition to view economic success purely as a question of power dynamics, delinked from effort and know-how.

A further critical point about skills needs to be made in the light of Professor Lawrence’s comments about the Fourth Industrial Revolution, quoted above. Simply, it is that while it may be true that many new jobs will be created, it is painfully obvious that our existing workforce lacks the skills needed to shift into service industries or jobs, and that our educational system is, at best, woefully inadequate to produce new entrants to the labour market equipped to succeed.

Towards a recipe for export success

The challenges of upskilling the labour force and creating some sort of local market are far from insuperable, given political will and enough of a policy change to convince local investors to unlock their vaults. Although it is unlikely given the current state of the ruling party and its outdated economic thinking, if we did manage to ignite local demand and had sufficient of the right skills, how might we achieve success in international markets?

Professor Saville notes that successful exporters tend to have either a single large trading partner (Mexico and the United States come to mind) or they are part of a “neighbourhood” in which learning by contagion occurs. Asia is a good example: Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, China, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines have learned from each other, and exchanged places on the manufacturing supply chain over the decades. The same point could be made about Europe.

South Africa has neither – but what it does have is close proximity to some of the world’s fastest-growing economies. “Big business tends to focus on more distant markets or, at best, Nigeria,” he says. “We are ignoring big opportunities on our doorstep.”

Careful targeting of African markets is thus one option that would effectively play to our strengths, among them market proximity and understanding.

Another avenue suggested by Professor Lawrence is to specialise in what we are good at and can deliver at world prices. One such area is capital equipment, says the SACEEC’s Bruggeman. He says South Africa already exports capital equipment valued at around R178 billion annually, and has an excellent reputation for specialised and innovative products, particularly in mining and agriculture. He also says that bespoke versions of generic products, such as suction pumps, are a good niche.

“We could double our production capabilities if we had a proper exim bank to finance our trade. Specifically, we could play a bigger role in the many African projects underway and planned,” he says. “There is huge potential – we just need to unleash it.”

_____________

What are the African opportunities for South African manufacturers?

Given their distance from the markets of the developed world, and the extreme competitiveness of those markets, it seems to make sense for South African exporters to look to nearby African countries as export markets. After all, many of these are among the world’s fastest-growing economies. Presumably, too, South Africans have some fundamental advantages such as their relative closeness to the market, experience of African business conditions and practices, and a highly developed financial and governance framework.

Most important of all, many citizens of target countries regularly visit South Africa to shop, have relatives working here or indeed are sending their children here for some portion of their education.

The African Continental Free Trade Area agreement, which South Africa has pledged to sign, is likely to further streamline intra-African trade.

Liz Whitehouse of Africa House says that in 2017, South Africa’s exports to sub-Saharan Africa amounted to $23.2 billion, and that 35% of all value-added exports from South Africa go to this region – thus falling into the broad manufacturing category. This means that our producers know what these markets want, but also that there is considerable potential for expansion, she argues.

Of particular note, surely, is the fact that many manufactured products are maintained and serviced from South Africa – a clear example of the multiplier effect of manufacturing.

However, there are massive regulatory and infrastructure hurdles that need to be borne in mind. Tutwa Consulting’s Lesley Wentworth and Peter Draper warn that potential minefields include negotiating local gatekeepers, contact with whom might jeopardise the whole venture in the long run – McKinsey’s experience with Trillian Capital is a lesson to be taken to heart. Other barriers would necessarily include entrenched incumbents who will do what they can to prevent new market entrants, and the potential for locals to resent South African entry into their markets.

Ms. Wentworth and Dr. Draper detail a general approach would-be exporters into Africa should follow, one that can be tailored to individual circumstances. This approach would include a proper political economy assessment, with desktop research backed up by several in-country visits, to understand the market’s potential and what its barriers to entry would be.

The key, they say, is to remember that one will be “navigating ‘frontier’ circumstances and ‘institutional voids’, meaning that adaptations en route are inevitable”.9

The SACEEC’s Eric Bruggeman debunks the notion that South Africans are routinely seen as arrogant. “South African companies are in the main careful to employ and train local people, and our goods are valued,” he counters. “You are much more likely to hear complaints about the Chinese, who frequently bring in their own employees and are often perceived to be dumping.”

However, the Chinese continue to make headway because they are able to finance projects for African governments that are chronically short of capital. Mr. Bruggeman believes that if South Africa had a proper exim bank that could fund such projects, it could clinch major infrastructure deals.

According to a report from the African Development Bank, Africa needs to spend $130-170 billion a year on infrastructure, with a financing gap in the range of $68-108 billion.10

He says the right moves are beginning to be made, with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between the Export Credit Insurance Corporation of South Africa (ECIC) and the Afreximbank in March for a $1 billion financing programme to promote and expand trade and investments between South Africa and the rest of Africa.

The ECIC is a state-owned corporation of the Department of Trade and Industry.

“We exported capital equipment into Africa worth R44 billion over the past two years – we could triple that given the right funding mechanism,” Mr Bruggeman says.

If we are serious about growing our manufacturing base, and it seems we should be, then the opportunities offered by fast-growing African markets – with all their challenges – should not be missed.

Exporting to Africa: The basics

While every African market has its own characteristics, Tutwa Consulting’s Peter Draper and Lesley Wentworth say there is a general approach that can be used to formulate a country-specific entry strategy.

· Understand how to use informal institutions. Because many sub-Saharan countries lack formal intermediaries, regulators, and ways of enforcing contracts and resolving disputes, companies must be prepared to use informal institutions, build personal connections and put up with opaque power arrangements. Understanding the nuances of local culture will be critical.

· Develop a detailed risk profile. Many of these are “frontier markets” with unique risk profiles, often a combination of corruption, arbitrary rules, and faltering democratic rule and economic prosperity.

· Assess the markets thoroughly. A good assessment of the political economy is the essential starting point. This should include an assessment of political risks, and market-scoping. Based on this, the risk/ reward of alternative markets can be compared.

· Know how the figures work. Databases and indices covering Africa have distinct peculiarities, so each one’s basic principles must be fully understood when researching.

· Expose yourself to the markets. Desktop research must be complemented by comprehensive in-country visits.

· Ensure a receptive market. Design a (benign) strategy to influence key local stakeholders to ensure greater market receptivity.

· Proceed with caution.

Adapted from Peter Draper and Lesley Wentworth, Exporting in Sub-Saharan Africa – Worth the effort? (6 February 2018), available at http://www.tutwaconsulting.com/exporting-in-sub-saharan-africa-worth-the-effort.

1 The CDE’s summary of Professor Lawrence’s various talks, The future of manufacturing employment, is required reading for anyone involved in or thinking about manufacturing. It is available at www.cde.org.za/the-future-of-manufacturing-employment.

2 Adapted from ibid, Table 2, p 5.

3 Ibid, Table 1, p 4.

4 South African Institute of Race Relations, South Africa Survey 2018.

5 Ibid, p 6.

6 Quoted by The Manufacturing Institute at www.themanufacturinginstitute.org/Research/Facts-About-Manufacturing/Economy-and-Jobs/Multiplier/Multiplier.aspx.

7 South African Institute of Race Relations, South Africa Survey 2018.

8 JSE figures, supplied by Ian Cruickshanks, South African Institute of Race Relations.

9 Peter Draper and Lesley Wentworth, Exporting in Sub-Saharan Africa – Worth the effort? (6 February 2018), available at www.tutwaconsulting.com/exporting-in-sub-saharan-africa-worth-the-effort.

10 ‘Massive’ infrastructure spending needed in Africa, says report, News24 (18 January 2018), available at www.news24.com/Africa/News/massive-infrastructure-spending-needed-in-africa-says-report-20180117.