South Africa’s Climate Change Bill gives a good legal definition of climate change: “‘Climate change’ means a change of climate that is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and that is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods.”

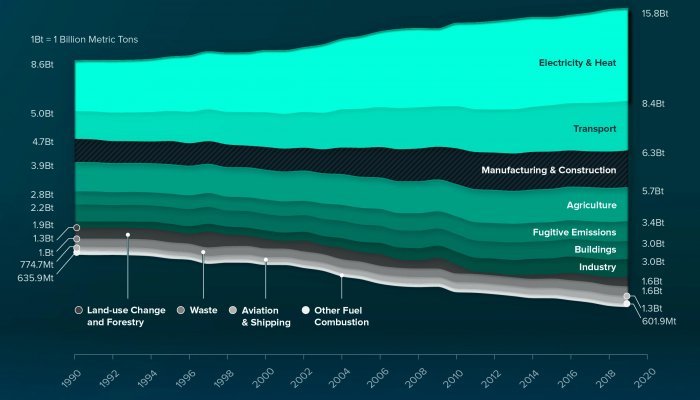

This definition clearly states that climate change is directly linked to human activity. These activities can primarily be connected to the production of energy and goods, transport, and the alteration of the natural environment. In a nutshell, this refers to business activities.

[Note from author: great graphic https://www.visualcapitalist.com/sp/the-biggest-contributors-to-climate-change-by-sector/]

South Africa and climate change legislation

Over the last two decades, South African climate law has evolved to keep up with what is happening on the international stage. Andrew Gilder, a director of Climate Legal, says, “We've seen policy and law evolving around the five core issues that are dealt with at the international level – primarily mitigation and adaptation, but also capacity building, finance and technology transfer.”

Over the last five years, however, the South African government has become even more focussed around climate change issues. “We have seen government moving towards a much clearer articulation of what South Africa and South African companies need to be doing to contribute to the global response to climate change,” says Gilder.

From a local legal point of view, business needs to know where South Africa stands in terms of its regulatory frameworks. Gilder explains that there is “quite a complex and evolving legal ecosystem” which is intended to support the national contribution to the international climate change response.

The South African legal frameworks around climate change include:

- the Constitution,

which entrenches the right to an environment not harmful to health or well-being. - the National Environmental Management Act of 1998,

which doesn’t reference climate change but provides a basis for managing the environment, such as the principles of sustainable development, precaution and polluter pays. - the National Air Quality Act 2004,

which provides for a national air quality legal regime. Air quality and climate change are different technical and legal concepts because air quality is a local concern while climate change is an international issue. - the National Greenhouse Gas Reporting Regulations and the National Pollution Prevention Plan Regulations of 2017,

which require reporting of greenhouse gas emissions under the South African Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reporting System, and the development and implementation of emissions management plans. These laws, along with the Carbon Tax Act, are linked to the Climate Change Bill. - the Carbon Tax Act of 2019,

which was first envisioned in 2006 but only became law in 2019. - the Climate Change Bill (B9-2022),

currently before Parliament which, when passed, will be the country’s flagship legislation on climate change.

The Climate Change Bill

Gilder and Olivia Rumble – who is also a director at Climate Legal – are specialist climate change legal advisers to Government for the drafting of the Climate Change Bill, and had hoped for a dedicated climate change statute some years ago. Administrative and other delays, however, means that they are now hoping that the Bill becomes law in 2023.

Rumble explains that the Bill seeks to “ramp up the existing monitoring, reporting and planning regime and to introduce a system of carbon budgets that cover reportable and taxable greenhouse gas emissions.” Companies and large-scale emitters will be allocated “carbon budgets,” and will be required to take steps to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to remain within their set budgets. Rumble believes it is likely that businesses that over-shoot their allocated carbon budgets will pay punitive levels of carbon tax on excess emissions.

Rumble stresses that Government has been transparent in forewarning business that carbon budgets are coming. A system of voluntary carbon budgets has been in operation for some years and businesses have had the opportunity to start working on their long-term capital expenditure and operational expenditure costs to manage their transition to compulsory budgets. Gilder notes that once the Bill is enacted as legislation, companies are likely to still have a number of years to ‘learn by doing’ before they get sanctioned for non-compliance.

The Bill also addresses the country’s greenhouse gas emissions trajectory. The Nationally Determined Contribution describes the commitment that South Africa made under the Paris Agreement to reduce its national emissions trajectory. The Bill will effectively turn South Africa’s commitment into national law and make it legally binding on the government, business and civil society. In addition to companies having carbon budgets, whole sectors will also have carbon budgets, such as departments of energy, transport, and agriculture, as well as municipalities. They will all be legally obliged to have plans in place to assist in meeting the national targets, and this will impact businesses operating within these sectors and regions.

The business risk of climate change

While South African law is growing teeth to force greater compliance, it is still relatively lenient. Brandon Abdinor, a climate advocacy lawyer at the Centre for Environmental Rights, says, “National Treasury has proposed to progressively increase the carbon tax till 2030. By when, we'll be looking at a carbon tax of up to $30/tonne. Global expertise suggests that for a country like South Africa it should be around $75/tonne by 2030. That’s still low. If you look at the social cost of carbon, which measures the financial impacts of carbon emissions on society, conservative estimates suggest carbon tax should be $300/tonne. But if you truly think of what it means, some experts say it should be as high as $3 000/tonne.”

Professor Tracy-Lynn Field, who is the Claude Leon Foundation Chair in Earth Justice and Stewardship, however, says that businesses need to stop viewing climate change purely from a legal compliance perspective. She says that businesses need to understand the business risk of not addressing the issue.

Prof. Field says that while climate change is a very emotive issue, it is critical for business to engage with the climate science. “There is a lot of research on this, brought together by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s review process, which brings the rigour of science and rationality to the issue,” she says. “We have 20 years of work to draw on.”

But if the state of the environment and the accompanying laws are not enough to motivate businesses to change, then the economic risks may be more effective. Field notes the threats are real. In two of her case studies, businesses with sunk investments had to invest R14 million and R400 million, respectively, to adapt their businesses to survive the impacts of climate change. This is not including the cost of lost operational capacity.

South African businesses, depending on their location, face the physical risks associated with climate change that include increased risks of floods, tropical cyclones, droughts, wildfires and heat waves. These events will put additional pressure on water and food security, explains Abdinor, and will see people migrating from heavily impacted areas, which is another risk for businesses who are unable to move themselves. The cost of energy will also continue to increase significantly. “Being climate smart is being resource smart,” says Abdinor.

Abdinor adds that non-compliance may result in a loss of business. “If you are a business that supplies to, say, a big business that is taking climate change and its emissions targets seriously, you are going to be audited,” he says. It will be similar to the current broad-based black economic empowerment (B-BBEE) requirements.

Companies must also be aware that their success is increasingly based on the social licence to trade. Many investors and consumers are now demanding that business take the climate issue seriously. Abdinor warns against greenwashing. He says, “We are starting see legal pressure come from that. In the United States, a lot of fossil fuel companies are being taken to court for greenwashing.”

Zero-global participation

Yet, it is international laws that potentially pose the greatest risk to South African business. International communities, the European Union (EU) in particular, are becoming very strict around combating climate change. As such, a number of their laws and regulations will directly impact South African businesses.

The pledge for net-zero by 2050 is putting pressure on global businesses and financiers to withdraw funding for new fossil fuel developments. Field highlights the work of the G20’s Task Force for Climate Financial Disclosures, which recommends that all businesses – but particularly the financial sector and sectors acutely vulnerable to climate change, such as construction and mining – should disclose their climate change risk in their annual filings. These include the costs of physical and transition risks, such as complying with climate-related legislation.

But perhaps one of the most impactful laws, says Abdinor, is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which will see EU countries heavily tax imported goods with a high carbon footprint. That includes products made by power generated from fossil fuels and energy-intensive manufacturing processes. This means that South African exports could become increasing undesirable with some of our largest EU trading partners.

Benefits of onerous international legislation

While many stakeholders question why South Africa is committing to global climate change agreements, arguing its economic size and contribution to climate change are insignificant, Gilder stresses that South Africa gets great benefit from participating in the international climate change legal regime. He says, “benefits around technology transfer and financing [...] are issues intimately connected with the Just Energy Transition. Those deals are being unlocked by our participation in the multilateral arena, under the auspices of the Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement. If we were not in that club, we would not be in a position to benefit in that way.”

Adapt or die

Field sums up the issue for business by saying, “I think there are going to be a lot of maladaptive responses in business behaviour, but the successful companies in the future will be those that are able to navigate the risks associated with climate change.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Climate change is an issue that South African businesses can no longer ignore.

- South Africa is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, which is a legally binding treaty to address the global climate change crisis.

- The country has various laws that have been designed to bring local companies in line with global emission standards.

- South African businesses need to stop focusing on legal compliance, and be aware of the business risks associated with climate change.

- Businesses need to engage more proactively with the climate science to understand the urgency of the issue.