Markets often get an unfair rap as creatures of selfishness. Of course, markets can be manipulated to be exclusionary, winner-take-all, and exploitative beasts. However, functioning markets feed economic and social inclusion. A winning entrepreneur building a competitive business can bring a whole community with her. Cases in point are the economic stories of the two Germanies and the two Koreas.

American economist and author Todd G Buchholz captures the elegance of this phenomenon, perhaps invoking the spirit of Scottish economist Adam Smith and his metaphor of the “invisible hand”:

“Market competition leads a self-interested person to wake up in the morning, look outside at the earth, and produce from its raw materials, not what he wants, but what others want. Not in the quantities he prefers, but in the quantities his neighbours prefer. Not at the price he dreams of charging, but at a price reflecting how much his neighbours value what he has done.”

If you are moved by that analysis, you’ll agree that unleashing competitive market forces might be the backbone of a broad-based South African economic revival.

But how? As Buchholz’s quote indicates, businesses are not islands. They are boats in an interconnected ocean, often rising and falling on the same tide. One of those tides is a route to market. In fact, plugging into supply chains is often the limiting factor for small businesses. Even though access to capital and skills attract the bulk of attention from policymakers and donors, it is often the case that being shut out of markets is the single-greatest hurdle entrepreneurs face.

With all of this in mind, three years ago the GIBS Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM) set about designing an experiment. Our question: how do we help small, high-potential businesses plug themselves into major supply chains?

South Africa’s macro structure: Best for big business

Before embarking on such a mission, it is critical to understand the market structure. “The data confirms the popular gripe that South Africa is sorely lacking in small businesses,” begins CAMM director and GIBS professor Adrian Saville. “Compare us to other emerging markets and you’ll find we have vanishingly few small businesses. A place like Mexico has around 4 500 small businesses per million people. In South Africa it is more like 1 200.”

That is not to suggest big businesses are bad. They aren’t. They are just different. With their mighty balance sheets they can do things small businesses can’t. That brings all sorts of benefits and impacts, from jobs, capital investment, and innovation to exports and contributions to the fiscus. However, it also tends to be the case that when large firms grow, it is through capital and gains in productivity – and not more jobs.

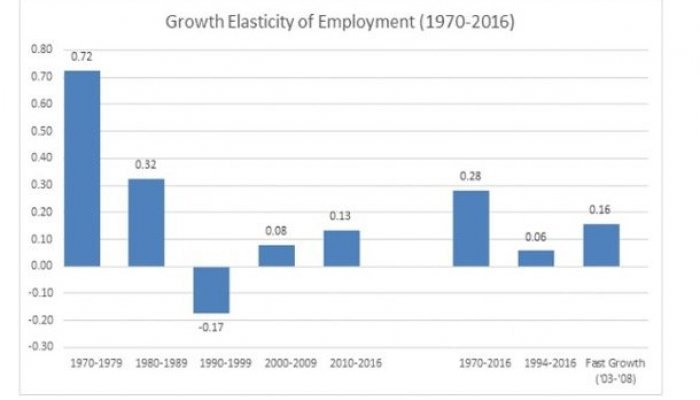

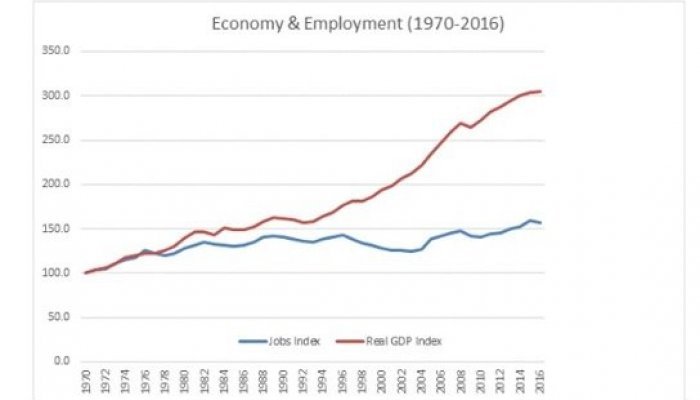

Saville captures the value of small businesses as employers: “Our employment elasticity of growth is very low. High elasticity would mean that a small amount of economic growth produces a high number of new jobs. In South Africa, we experience close to zero elasticity at times.

“That means we have jobless growth. One might ask, how can we grow without adding jobs? Well, as noted, big business in particular can increase volumes without adding headcount. It can add capital and boost productivity with things like technology to meet heightened demand.”

Again, that is not a bad thing. This is big businesses being efficient and returning value to shareholders during good times. However, if we want to improve job numbers, we must look to small businesses.

Low-hanging fruit

Our market structure (as part of the wider context) leaves us with unemployment of more than 30%. While we should lament this, we should also approach the solution with the right attitude. Starting from a low base has benefits.

Saville continues: “Because of our lowly starting point, we can make large strides with simple steps. Micro businesses that provide uncomplicated products and services will yield the best returns for our efforts.

“This helps us to focus. The greatest returns lie in giving the largest number of micro businesses the best shot at growing into small businesses.”

So, with its partner Aspen Pharmacare, CAMM put out a call. We launched a campaign inviting small businesses in the medical industry to apply for the Aspen-GIBS Route-to-Market Challenge. An online questionnaire got entrepreneurs into the challenge.

Through a careful vetting process, the CAMM team, with our evaluation and selection partner Raizcorp, chose five finalists who would join us at the Illovo campus for a one-day entrepreneurial immersion. Here we focused on guiding entrepreneurs on how to pitch their businesses to potential partners.

Then the real test came. Finalists pitched to an esteemed panel of business leaders including Stavros Nicolau (Aspen Pharmacare), Allon Raiz (Raizcorp), Lee Naik (TransUnion), Tebogo Skwambane (WPP South Africa), and Nomsa Nteleko (OS Holdings).

The prize would not be money or training, but rather an opportunity to engage with the procurement team at Aspen.

Francois Fouche, CAMM research associate, muses on this. “This actually felt uncomfortable. We are used to a prize being tangible, like a financial reward. But we had set out to address a particular problem in a novel way. Our goal was to foster new synergies. How could we guarantee that? We couldn’t. So we took a page from the entrepreneur’s playbook and created the conditions for success, not knowing if it would happen.”

The interactions between the 2023 winners and the Aspen procurement team are, of course, private. How can we measure if the Challenge was a success?

Well, Aspen partnered with us again in 2024 and we extended the scope. DHL Express Sub-Saharan Africa joined in with a new wing to the competition for logistics businesses. This meant an additional set of judges: Hennie Heymans (DHL), Allon Raiz (Raizcorp), Anthony Beckley (DHL), Thulani Nala (DHL), and Dr Faith Mashele (GIBS).

Evidence of impact: Back to basics

As anyone who has started a business knows, no business is simple to operate. In this context, we are talking about the economic complexity of products or services. This concept is best outlined and analysed by the Growth Lab at Harvard University. It measures the complexity of a product with reference to the depth and variety of skills required to produce it. For example, mining lithium is relatively low on the economic complexity index (ECI). But designing and producing lithium-based batteries is high on the scale. Thus, complexity in this sense is not necessarily related to the complexity of running the business.

The winner of the logistics and supply chain pillar of the competition, the DHL-GIBS Route-to-Market Challenge 2024 edition, exemplifies the power of starting with a clear strategy – even if you start small.

Colin Mkosi is the founder of Cloudy Deliveries. The law graduate operates his bicycle delivery company in Langa, Cape Town. Transporting primarily groceries and restaurant meals short distances to customers’ homes, the small but growing business is transforming lives.

Consider first the several dozen youngsters that Colin employs. Because they are mostly lacking the skills required for a mainstream job, Cloudy leverages their understanding of the community, not to mention youthful legs and lungs – most riders are under 20.

For the broader community, where the big names in food and grocery delivery don’t go, they can get food and necessities delivered, rain or shine, for as little as R30.

Mkosi’s micro business, needing only bicycles, WhatsApp and some dedicated youngsters to get off the ground, has grown into a thriving small business.

And it is going places.

“Members of our senior leadership have toured Colin’s facility,” explains DHL CEO Hennie Heymans. “Based on our expertise, we have been able to advise on ways Cloudy Deliveries can introduce new operational efficiencies.” Several initial projects between the two businesses include improved signage, upgraded solar power generation and route-planning tools.

What next?

While creating micro businesses will continue to yield the greatest impact for the largest numbers for years to come, we need to be ready to grow these into small, medium and then large businesses as they emerge. This is where building greater economic complexity into products helps.

Francois Fouche explains. “To make a complicated topic very simple: the greater the economic complexity in a product, the more prosperity we generate by making and selling it.”

More complexity means harnessing more skills and participating in more of the value added along a supply chain. The 2024 winner of the medical pillar of the competition, the Aspen-GIBS Route-to-Market Challenge, offers an illustrative example.

Ortho-Design, founded in 2017 by Tim Peach, manufactures biomedical devices for orthopaedic surgery. Products include the likes of anchors that surgeons use to attach soft tissue to bone. Peach manufactures in South Africa, but the US export market is his dominant destination.

A biomedical engineering Master’s graduate himself, Peach’s operation needs an increasing number of highly skilled staff, all injecting economic complexity into their products. The team includes a variety of engineers, a devoted research and development team, and cutting-edge software development capabilities. They work closely with surgeons to meet exacting needs.

Peach reflects positively on his journey. “Engaging in an in-depth discussion with senior leaders of top South African business is invaluable. While we may not yet know the specific opportunities that could arise out of conversations with Aspen, we will make the most of it.”

The CAMM team is already preparing to launch the 2025 Route-to-Market Challenge in an expanded format. Much like the businesses we are capacitating, we remain focused on the basics, gradually building in complexity as we go along, and bringing as many people with us as we can.