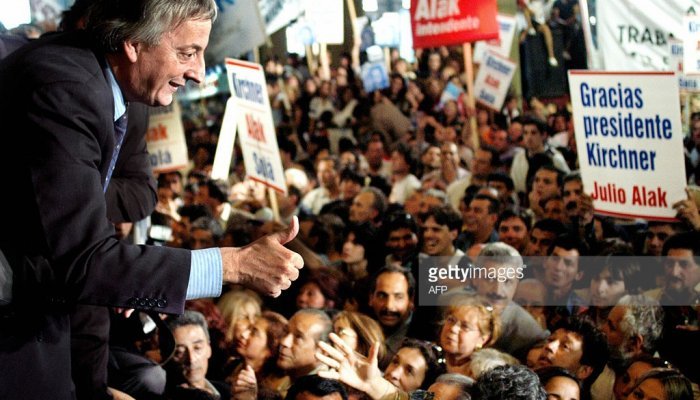

When the little-known Néstor Kirchner ran for Argentina’s presidency back in 2003, he promised to restore his South American nation’s reputation as “a serious country”. It didn’t happen.

It was a message designed to appeal to an electorate battered by the humiliating sovereign debt default of December 2001 that turned what was once one of the world’s richest societies into a financial pariah, cut off from global capital markets and shunned by foreign investors.

That epic default capped a long and unprecedented decline in the country’s fortunes. At the outbreak of World War I Argentines earned as much as Germans, the Dutch and Belgians and far more than the workers of former colonial master Spain. But by the time Kirchner was sworn into office, a brutal five-year recession had dumped over half the population of what had once been a proud outpost of the developed world’s middle class into poverty.

Goodbye, Mrs Kirchner

Thirteen years later the Kirchner era is now drawing to a close. Néstor died suddenly of a heart attack in 2010 but by then had already transferred the presidential sash to his wife Cristina, whose second term ends in December. She is leaving office claiming that her family’s self-styled “Victory Decade” in power has restored the country’s fortunes.

But most foreign investors would disagree and have yet to reintroduce Argentina onto their business itinerary.

For one thing a botched 2005 debt restructuring means the country remains shut out of capital markets almost 14 years after the default. The Kirchners offered creditors a brutal take-it-or-leave-it write down on their investment. Some left it and have snarled up Argentina’s hopes of a return to markets in US courts, so successfully they even forced the country into another default last year.

Foreign direct investment which flooded the country in the 1990s has been scared off by price controls in crucial sectors like energy and transport and the forced renationalisation of companies the state had only recently sold off. This lack of investment has produced bottlenecks which in turn are fuelling the old curse of inflation. When that started getting out of hand the government responded by firing the economists responsible for compiling its statistics and replacing them with Kirchner supporters. They, unsurprisingly, reported a far lower figure which the IMF refused to use in its reporting.

A beef about steak

Initially, Néstor was able to play fast and loose with economic orthodoxy because he assumed office just as China’s voracious demand for commodities was shocking Argentina’s economy back into life. The vast Pampas grasslands grow a sizable chunk of the food consumed by increasingly affluent Asians and, as the price of soy and other foodstuffs soared, the government in Buenos Aires suddenly found it had access to billions of dollars thanks to export taxes.

Néstor used this unexpected soy bonanza to fund a vote-winning splurge in public spending that helped pull down the stratospheric poverty rates that followed the default. But other exports were sacrificed to political expediency. When the cost of Argentina’s famous steak started to rise, beef exports were restricted to force down domestic prices. The result was a dramatic decline in the country’s once legendary national herd.

Eventually, the soy effect lost much of its punch, forcing the government to scramble around in recent years for other sources of income to fund its increasingly profligate spending. A 2008 effort to increase taxes on soy exports was defeated by farmers and so the government nationalised the pension system instead.

This funding problem has grown even more acute with the slowdown in China and the impact that has had on the soy price. Still unable to access markets to cover the growing deficit, Cristina’s administration has resorted to the old Argentina tactic of printing money. Despite the “Victory Decade”, she will leave her eventual successor one of the world’s highest inflation rates, dwindling foreign reserves, a yawning fiscal deficit and still unable to access to capital markets.

The problem with Peronism

It is little wonder investors have given the country a wide berth. Despite its huge potential, foreign direct investment has lagged behind smaller regional rivals meaning Argentina missed out on much of the last decade’s record inflows into South America.

“The Kirchners ran a classic populist economic policy that prioritised the internal market and keeping people happy at the expense of integration with the wider world,” says Dr. Samuel Amaral, a historian of the couple’s Peronist movement.

It is a policy mix that explains the divergence in how the Kirchner years are perceived by ordinary Argentine voters and the investor community. But it is a model that has finally run out of steam, its myriad internal contradictions and inefficiencies exposed by the downturn in Chinese demand for its few cash earning exports. Argentina is once again mired in recession with poverty back on the increase.

So why are investors suddenly optimistic about the country’s prospects? Bluntly put, because Mrs Kirchner will be quitting the Casa Rosada on December 10th. “In this election the question of who wins is secondary to the fact that it marks the end of the Kirchner era,” says Dr. Amaral.

Who’s next?

The two frontrunners in the race to succeed the president are the governor of Buenos Aires province, Daniel Scioli, and the former mayor of Buenos Aires city, Mauricio Macri.

The son of an Italian-born industrialist and the former president of Boca Juniors, the country’s most popular football team, Macri had a mixed record as the capital’s mayor but is running a strong second in national polls. Amazingly, he is attempting to become Argentina’s first ever democratically-elected right-wing president. Even his ideological opponents acknowledge that he represents an advance in a country where the right traditionally relied on the military to exercise power with the pro-Kirchner intellectual Horacio Verbitsky hailing the “emergence of a modern right-wing that observes the rules of democracy and has electoral potential”.

His main challenge now is overtaking the frontrunner, Daniel Scioli, a former powerboat champion who, as governor of Buenos Aires province, cemented his reputation as a consensus builder in Argentina’s take-no-prisoners political culture. Like President Kirchner he hails from the populist Peronist movement and his bid has her backing, despite a difficult relationship ever since Scioli ran as her husband’s running mate back in 2003.

But this support does not mean a Scioli presidency would be a continuation of the Kirchner era.

“Scioli and Macri broadly agree on foreign and economic policy and are very different to President Kirchner in their view on the role of the state in the economy for example,” says Sergio Berenszstein, one of Argentina’s most perceptive political analysts. “As incumbent, Scioli would be different ideologically to Cristina and in fact more like Macri.”

Investors, at least, seem sanguine about which one emerges as the winner. Some prefer Macri’s more explicit commitment to orthodox economic policy. But others worry about the damning fact that the last non-Peronist elected president to see out his full term was the Patrician Radical, Marcelo T. de Alvear, in 1928.

Some investors therefore wonder if it would not be better to have a Peronist in charge of reinserting Argentine into the global economy as he would be better able to discipline the party’s governors and likely majority in Congress. The party’s ideological fluidity means Scioli’s current praise of Mrs Kirchner’s administration should not be taken at face value. After all he entered politics first under the wing of the Peronist playboy president, Carlos Menem, who in the 1990s liberalised and privatised the economy with all the fervor of a Chicago Boy.

“Henry Kissinger was once asked what presidents want and he replied ‘a second term’. If either Scioli or Macri wants a second term they will need to make changes to the economy because without them there will be no growth and they will not be re-elected,” says Alberto Bernal, an economist with Latin American investment house Bulltick. “Both men understand this. They know what they have to do.”

Pay the Vultures

Topping the to-do list is a settlement with the bond holdouts that would pave the way for a return to capital markets. President Kirchner has inflated the dispute into a principled stand against what she labels “vulture funds” preying on the country’s poor. But the amount of cash in question is relatively small and a deal would be a powerful signal that Argentina is reopening for business.

“If the country fixes its external accounts so much money could suddenly flood in it is not even funny,” says Bulltick’s Bernal. Easier access to capital, the unwinding of costly subsidies and a less populist approach to public spending would also clear the path for desperately needed new investment in infrastructure with the country having a host of opportunities waiting to be explored in sectors such as energy and transport.

It is these expectations of better times ahead for investors that explain the rally in Argentine bond prices as the vote approaches. But some observers urge caution. In recent months President Kirchner has been making unprecedented efforts to pack her loyalists into senior positions in a bid to preserve her influence after she leaves office. Her son, Máximo, is set to be elected to congress where he will look to lead the kirchnerista bloc within Peronism and she imposed a close confidant as Scioli's running-mate as the price for her support.

Cynics have pointed out that the president’s main motivation now is not ensuring that its populist ideology continues to hold sway under her successor. Instead, she is trying to prevent the courts finally investigating the many corruption scandals that marred the Kirchner era and saw the family’s wealth balloon, while close friends used their proximity to power to become multi-millionaires.

But history is against her. “Cristina wants to preserve her influence after she leaves office. But she will no longer be president and in Argentina, the presidency is very strong. It is going to be difficult for her. There are few cases of former presidents remaining strong after office and the corruption scandals will take a toll on her reputation,” predicts Berenszstein.

Though the winner is still to be decided at the ballot box it seems Argentina’s latest populist revival is drawing to a close.

A hug, then a kiss

Like most of Latin America, Argentina’s business culture is relatively closed and outsiders often have a difficult time gaining a foothold in the country. Building personal relationships is key. When starting off remember lots of eye contact and do not be surprised if after a few meetings a hug replaces the salutary handshake. Between men, you know you have established a friendship when, on meeting up, a kiss in the Italian manner replaces the hug.

Because the judicial system is so slow and corrupt there is a premium placed on establishing trust between perspective business partners. So plan on spending plenty of face time with your contacts and remember rambling, unnecessary meetings with little or no agenda are often just an excuse for locals to weigh you up.

So arrive ready armed with plenty of small talk. Argentines are unusually sensitive about how outsiders view their country so let them know how excited you are to visit and how much you are looking forward to the steak and wine. Sport is always a popular topic, especially football. Any expression of interest in seeing a game on your visit might lead to an invitation to a match.

Argentina’s business class speaks good English, is well travelled and despite its government’s policies thinks of itself as part of a global network. But there are cultural differences. Arriving at a meeting and getting straight down to business is considered rude but taking a call during it or talking as opposed to whispering during someone else’s presentation is no big deal. Also Argentines eat late. If you are arranging a business dinner, do not think of booking a table before 9pm.