Approximately 80% of the businesspeople to whom I pose that question opt for brilliant strategy. Personally, I don’t think it’s the right answer.

Two reasons. Firstly: if I asked you to give me a strategy, I would expect that your response might be, “For what?” That’s telling. It demonstrates that a strategy actions something that precedes it. Strategy is not alchemy. It cannot manufacture non-existent value out of an idea. Its role is to enable value potential nested within the idea or set of ideas.

Often, what’s considered a strategy problem might actually be an idea problem. If ideas begin to lose relevance, the businesses built on them will also start to struggle. But performance declines are routinely interpreted as a combination of strategy and execution shortfalls, whereas they may actually be down to ideas that are losing relevance.

We fail to wring all the value from an idea.

As I see it, ideas either lose relevance because the perceived problem doesn’t exist, the problem state is morphing or the envisioned solution fails to adequately solve it. While that sounds obvious, management teams continuously rationalise how and why their problem/solution configurations are viable and relevant.

The second reason is that there is always strategy execution latency. Delivering on our best-laid plans takes longer, costs more and delivers less than envisioned. We fail to wring all the value from an idea.

Strategy over-reach and the need for foundational thinking

I hear things like, “We’re going to liberate value?” and I want to ask, “Where is it trapped?” Not many people are able to clearly articulate how to create, capture and extract value from their business. But if that’s the purpose of business, we need to make it an explicit input – it can’t be implied in the output. Unless we can do that, we can’t solve for value. This requires a deeper understanding of foundational principles, a common language and first principle thinking methods.

I’d argue that the general managerial understanding of the role that strategy plays in business is exaggerated. It’s seen as this higher order, all-conquering, grand plan responsible for defining and delivering us to a desired and better future state. And this “over-reach” points to a bigger issue in business – a lack of grounding in foundational commercial concepts and tools.

Reasoning from first principles is a deconstructive approach used to get to the heart or core of a concept. It strips away layers to break down complex concepts to essential building block ideas that are fundamentally true or true enough. These are called base or non-inferential beliefs. First principles are the foundations from which more complicated structures or ideas can be reliably built. Concepts like ideas, value, relevance, strategy, differentiation and growth are underpinned by foundational premises and relationships.

In an increasingly complex commercial environment, when we “under-understand” the foundational concepts we bandy about, we succumb (often unknowingly) to a “thinking tax”. It’s like trying to solve university-level maths problems with a primary school algebra understanding.

The BITS framework

In order to engage this problem, I’m proposing a foundational thinking and strategy derivation framework anchored around the concept of commercial value. The aim of this framework is to guide and empower management teams to explore, capture and document their best thinking as an effective way of grappling with strategic complexity.

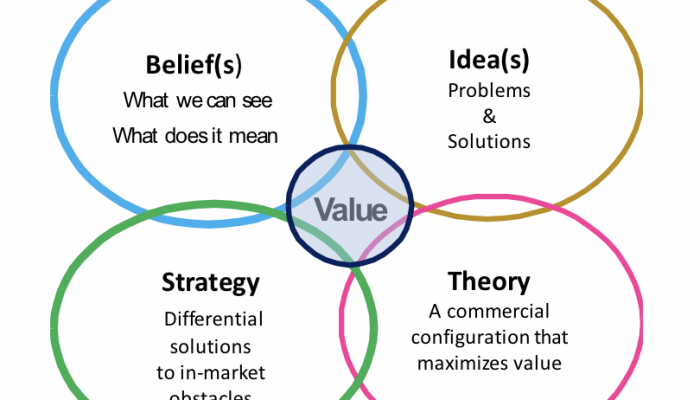

What I call the BITS framework divides thinking into four logically interconnected foundational layers: Beliefs, Ideas, Theories and Strategies. Together, these elements make up a company’s value path (the process of sourcing, designing and enabling value creation, capture and extraction).

Ideas don’t have to be new; they just have to be relevant.

An idea is expressed and delivered through a commercial theory. The theory asserts that a chosen asset, resource and activity design operated in a specific way will maximise all available potential within an idea. The chosen theory is usually one of many potential options.

Theories operated within contextualised markets offer specific and differing value creation, capture and extraction challenges. Strategy’s role is to overcome the theory and market challenges in differential ways. This requires co-ordinated action.

In combination, our beliefs, ideas, theories and strategies express our strategic narrative.

BITS in action – begin with beliefs

The starting point for BITS is to ask, “What do I believe to be true about the markets I compete in and customers I compete for?” The next question is, “Is this an accurate reflection of reality?”

Too often, even if we stop to ask the first question, we neglect the second. This leads us to trust our beliefs without checking them against reality. But beliefs tend to be deeply protected. We believe what we need to. It’s difficult to get people to consider the possibility that their beliefs may not stand up to scrutiny. Confirmation bias plays a large role – people will look for evidence to substantiate what they want to believe.

For example, I think the full-service advertising agency business model is set for major disruption within the next few years, and that much of this comes down to the fact that some of the ideas behind the model are losing relevance in clients’ minds.

...strategy’s role becomes very specific: it is a contextualised problem-solving tool.

While agencies may assume that they will manage the relationship between new digital platforms and their clients, the clients are moving towards separating digital technology strategy from content development and production. Where agencies still view themselves as the primary content idea generators, clients might be cutting back on agency-sourced content ideas and looking towards premium crowdsourcing instead. Large brands like Coca-Cola, Oreo, Budweiser and Pepsi are already using open innovation and co-creation models to source not only communication ideas, but also new product ideas.

Relevance check – identifying viable ideas

Ideas don’t have to be new; they just have to be relevant. Some ideas are enduring – like the one behind Disney – wholesome family entertainment. Entertainment is such a durable consumer need that as long as Disney can keep providing entertainment that is interesting and differential, that idea will serve the company forever. Relevance precedes differentiation.

A brilliant idea is a viable problem/solution configuration that offers a large amount of value potential (the amount of revenue, profit and return a business can extract from a commercial idea). In short, to offer value potential, an idea needs a sufficiently large set of customers to recognise the problem and why your particular solution design is worth paying for.

It’s important to note that the idea layer of BITS expresses what the idea is, and not how best to express or commercially exploit it.

Disruption usually occurs at the idea level. If an idea is beginning to lose relevance, it’s at risk of disruption. The problem state morphs or a new solution to the problem emerges. When competitors have found a better way to solve an old problem, you have a relevance challenge. Ideas get disrupted. Strategies get out-differentiated.

Making good on an idea – developing a commercial theory

Once you know you have a viable idea, you can work on a commercial theory to maximise its potential. The chosen theory is usually one of many potential options, so essentially, theories are a design and configuration challenge.

For example, one value theory might hold that it’s best to pay a retainer to a full-service advertising agency to manage all communications. Another might hold it’s better to bring certain competencies in-house and to work with specialist freelancers on an ad hoc basis. Both can deliver effective communications. It’s management’s role to pick the one that is most congruent with their core commercial idea.

Each will present its own set of challenges and this is where strategy finally comes into play.

Strategy as an enabler

Strategy needs to be addressed within the context of a preceding set of beliefs, idea and theory of value assertions. Rather than being the alpha and omega of management thinking, strategy’s role becomes very specific: it is a contextualised problem-solving tool.

Strategy asks, “What are the immediate and prioritised obstacles that need to be overcome, within the context of our value theory and market dynamics, coupled with a set of co-ordinated actions?”

As an enabler, strategy recognises that value is sourced in the idea, configured in the theory and made differential in strategy. It is the mechanism used to convert ideas and their theorised value designs into established and differential positions.

This is why differentiation occurs at strategy level. For example, all the major banks in South Africa offer Internet banking facilities, but the platform development, capabilities and functionality differ from bank to bank. The idea is the same, the commercial theory is probably very similar, but the strategy and execution are differentiated.

Where does your problem sit?

The BITS framework allows us to start asking and interpreting foundational questions. Figuring out whether you have an idea, theory or strategy problem is key to figuring what value you are leaving on the table.

Rather than assuming that a strategy is correct, or that performance problems lie at strategy level, it’s worth bearing in mind that strategy is not the source and creator of value, rather it’s the tool to enable and differentiate a pre-defined value design.