When the concept of the Global South was first introduced in 1955, the world was a very different place. After briefly disappearing as globalisation took hold, the unofficial alliance has recently seen a resurgence in popularity.

Partnerships like those of the BRICS+ group of countries, who want a collective departure from the Western dominance of world politics, trade, and economics, are gaining a greater share of the global GDP and have become more vocal and influential.

Is the Global South still relevant?

The resurgence of the Global South in recent years is a recalibration of power dynamics – both geopolitical and economic – in a rapidly changing world.

Historically, the Global South was united by shared struggles for development, economic equity, and political autonomy, mixed with an ideological association. This carried a connotation of solidarity against imperial powers, most notably the United States and Europe.

But today there seems to be a slightly different rationale underpinning the movement and growing interest in an apparent alternate global order from the South. This has shifted with modern-day geopolitical changes and new tensions in both power and influence, which carry a far stronger economic inclination. The Global South has come to mean something different to emerging powers. This is reinforced by the simple truth that the West (and notably the US) is no longer the only power in town. But what are the alternatives?

Increasing influence of emerging markets, the recalibration of international power centres, and a (seemingly) growing desire for a multipolar world order indicate that the Global South is evolving from a purely ideological or political bloc to a more strategic one.

But it does carry a strong anti-Western orientation or perhaps key factions within the Global South – notably Russia and China – are using this to drive an anti-US and anti-European agenda in the name of a multipolar framework.

Practically, and in the interest of the majority of nations, the Global South collectively seeks to reduce its nations’ dependency on Western financial systems, diversify their trade relationships, and develop new economic and political alliances.

“The rising popularity of the Global South term reflects renewed grievances against the global order … and reflects a desire for a new attempt at a more equal global order,” Erica Hogan and Stewart Patrick wrote for the Carnegie Endowment Fund earlier in 2024.

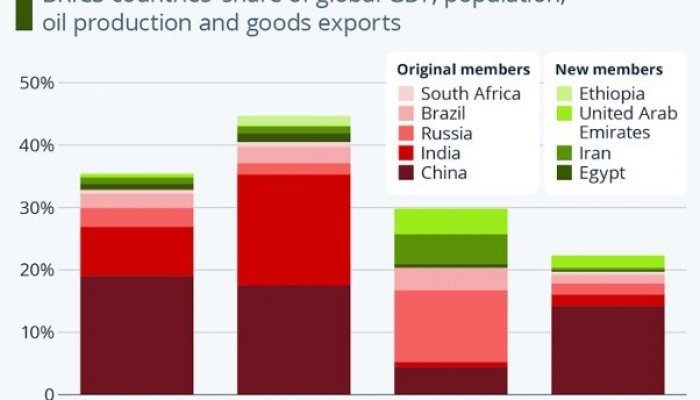

BRICS+, which in its expanded format now includes Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates, represents 45% of the world population and 28% of global GDP. In comparison, the G7 represents 10% of the world population and 26% of global GDP. (See Figure 1.)

The relevance certainly appears to have moved from pure demographics to economic might. It also represents the future. But is this future leadership countries of the South aspire to?

Despite their population size, share of global GDP, oil production, and goods exports, the countries’ political power and influence still falls short of their economic authority. This is best represented in the UN, especially around the Security Council and key decision-making bodies.

“The primary objective of the group is, or has become, global economic governance,” Francois Fouche, research fellow at the GIBS Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM), explained. However, he continued that “some countries are opposed to Western dominance, but do not agree among themselves on the actual alternative. As BRICS is a loose grouping of countries with almost nothing in common, the envisaged change in the global order is likely to be much slower than anticipated.”

Nothing in common?

Because the concept of the Global South assumes a collective identity, “it is patronising, factually inaccurate, a contradiction in terms and a catalyst for political polarisation. It is a deeply unhelpful term,” columnist Alan Beattie argued recently in the Financial Times.

We, as humans, long for straight-line trajectories, and hierarchical categorisations, which are – for the most part – unhelpful in understanding the world and interpreting its complexities.

“The lack of cohesion and ideological stance among the countries is problematic as they are not unified in their demands for reform,” Fouche said. Among the BRICS nations, there is significant disagreement about issues ranging from United Nations Security Council reform to climate change and whether Africa should be given a seat at the G20. Brazil, India and South Africa are all democracies, while China and Russia are not.

A multipolar world: The Global South and international trade

A United Nations report from the Conference for Trade and Development argued that “structural economic barriers still hold back the world’s least developed countries (LDCs) and keep them, to a large degree, dependent on commodities and vulnerable to external shocks.”

Apart from the sheer numbers in terms of population and their future trajectory, the Global South continues to be a highly relevant concept in the context of modern business and trade. These are the geographies where consumer markets are expanding, and economic diversification is rapidly taking place.

The improvements seen in the economic fortunes of several regional powers in the South seems to have accelerated the recent desire for realignment, as rising power has failed to be accompanied by privilege, or by political influence. However, attempts by the BRICS powers to create an alternative to the Western dominance of global economics and trade seem to have so far eluded the group.

The most recent BRICS summit, held in Kazan, Russia in October 2024, had the ambitious target of launching an alternative global currency to challenge the dominance of the US dollar, ushering in a truly multipolar world order.

“Many countries are opposed to the dominance of the US dollar as the default global currency, but it is significantly more difficult to implement a replacement currency,” Fouche explained.

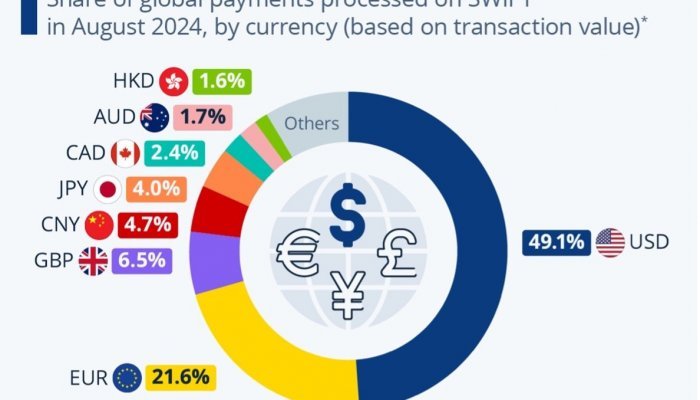

The dollar is entrenched as de facto global currency because it is highly liquid, widely accepted, and perceived to be a consistent store of value. (See Figure 2.)

“A multipolar world less dominated by America is a desirable outcome for some of the countries associated with the Global South. But for Brazil, India and South Africa, BRICS is a way of getting privileged access to China and nothing else. For Russia, the BRICS club is a defence against its pariah status,” Fouche said.

He questioned whether the concept of BRICS or the Global South had any longevity, given the diverging political and economic interests of the various countries that comprise the alliances, which typically grow out of common interests.

“I have very little hope for the future of BRICS. For the organisation to become meaningful, it would need a formal agreement and criteria for joining. It would also have to do something of significance and decide what it is they stand for, besides being against the dominance of the US,” he argued.

Where does South Africa fit in?

Historically, South Africa has straddled multiple geopolitical spheres, leveraging its position as the gateway between the Global South and the Global North. With its unique history, economic potential, and diplomatic reach, South Africa has consistently sought to bridge divides — whether as an African leader, a representative of emerging markets, or a voice for the developing world. But much has changed vis-à-vis South Africa and the rest of the world in recent years, and especially since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Most observers suggest South Africa no longer carries that influence in Africa or in the emerging world and has, as a result of its response to key issues, conflicts, or geopolitical tensions – especially where China is concerned – lost the moral high ground.

The economic realities suggest that while the likes of China represent exciting prospects for South African trade and business, the US and Europe remain South Africa’s most important trade and investment partners.

South Africa would be wise to heed the advice of the two largest democracies in the BRICS+ configuration, Brazil and India, and follow the example they have set when it comes to China, geopolitical tensions like the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, and global issues such as climate change and inequality. South Africa has more in common in its internal dynamics and global outlook with these countries than the others vying to shape the agenda of the Global South.

GIBS alumni and student views

Is the concept of the Global South still relevant?

“Countries like India and China are emerging above their Global South counterparts to become real disruptors within the world technological and economic space.”

Tumisho Makofane, GIBS MPhil Corporate Strategy student

“The concept of the Global South has become increasingly relevant in today’s shifting geopolitical and economic landscape, with unique strengths in energy, infrastructure, and technology that continue to boost its global influence. The Global South is not only a participant but a key shaper of the future economic landscape.”

Paulina Mamogobo, DBA (GIBS) and chief economist at NAAMSA – The Automotive Business Council

“There seems to be a swing toward a more nuanced understanding of global inequality, away from purely geographic distinctions and considering issues like digital divides, access to resources, and climate vulnerabilities.”

Emmanuel Osembo, GIBS DPA and director of regional operational and financial performance at FHI360

“The Global South retains a significant relevance in geopolitics today. The strengthening of BRICS+ is testament to a rethink by emerging markets on how to play a meaningful equal role in the direction the world is taking.”

Mhlanganisi Madlongolwana, GIBS MPhil International Business student

Is it beneficial for countries to belong to blocs such as BRICS+? Or should they rather focus on building their own bilateral alliances and trade agreements with other individual countries?

“Belonging to blocs such as BRICS+ has its own benefits. This includes access to global markets, which has facilitated technology transfers, export growth and investment flows.”

Tumisho Makofane, GIBS MPhil Corporate Strategy student

“Strategic alliances like BRICS+ are challenging traditional Western dominance in global finance and trade. As BRICS+ expands, so too does its capacity to fund major infrastructure and growth initiatives, levelling the financial playing field and granting greater independence to member nations. While multilateral blocs are powerful, bilateral partnerships remain indispensable for more customized, close-knit engagements, enabling nations to negotiate specific terms that meet unique regulatory standards, national goals, and market access needs.”

Paulina Mamogobo, GIBS DBA and chief economist at NAAMSA – The Automotive Business Council

“Countries have to be strategic in their alliances. Belonging to blocs like BRICS+, the EU and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) can be beneficial, but it depends on their specific economic, political, and strategic needs. Bilateral alliances allow countries to negotiate terms that are more precisely suited to their unique needs, industry strengths, and resources. This flexibility can sometimes result in more favourable terms than those achievable through a bloc-wide agreement.”

Emmanuel Osembo, GIBS DPA and director of regional operational and financial performance at FHI360

Professor Lyal White is a faculty member at the University of Pretoria's Gordon Institute of Business Studies (GIBS), where he is academic director of the Centre for Leadership and Dialogue (CL&D) and part of the school's Global Partnerships team. He is the founder of research and advocacy practice Contextual Intelligence, part of the OneEarth Leadership Consortium and a research associate with the Brenthurst Foundation.