“Almost everyone I have coached battles with effective delegation,” says seasoned GIBS facilitator Jenny Lorenzo, a skilled team and executive coach. “They get told they have to delegate but the ‘how’ is the tricky part. They struggle to let go.”

GIBS professional associate Thuli Segalo agrees wholeheartedly. She recalls a recent chemistry session with a potential coachee – let’s call him Rick – which was a blueprint example of the challenge many subject specialists face as they climb the leadership ladder.

Rick’s challenge

As a key talent within his company, Rick had been earmarked to transition from middle to senior management. However, Rick was battling to delegate. He knew his low delegation skills were getting in the way of building a strong team. He’d identified a few obstacles, including a fast-paced company culture that didn’t give him the space and time to work with subordinates. He also didn’t trust the quality of delivery from his direct reports. So, Rick just did the work himself. He knew that staying in his technical comfort zone was hurting his advancement into a more strategic role. How could he fix this?

Understanding the cognitive dissonance triggers that lead to this sort of behaviour starts with self-exploration. Lorenzo explains that her work in adaptive leadership focuses on understanding what prevents effective delegation. “What’s the blocker?” she asks. “What stands in the way? What’s the reactive tendency or defensive approach to anything that feels anxiety provoking, threatening, or stress inducing?”

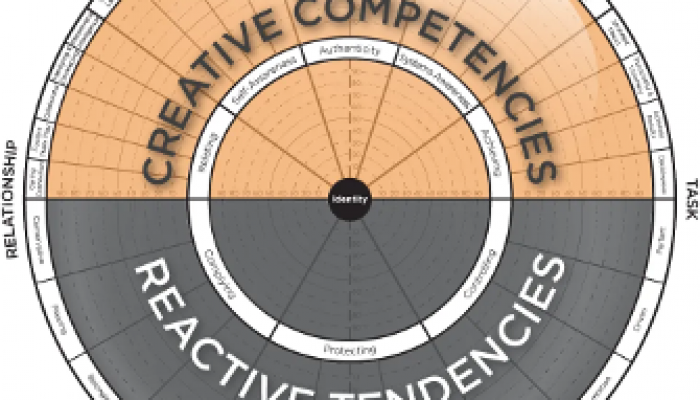

Authors of The Leadership Circle Profile Bob Anderson and Bill Adams highlight a range of default reactive tendencies that limit a leader’s ability to delegate. These could be one of several controlling behaviours, such as the need to be perfect.

Rick is a good example of this – he wants to deliver perfectly, doesn’t trust his team to meet his standards and so he struggles to let go. Similarly, a complying tendency such as people-pleasing could also limit a leader’s ability to share tough feedback. In this case, rather than risking disharmony such a leader might snatch the delegated work back and just finish it themselves.

Ultimately, says Lorenzo, leaders need to identify the root cause of their resistance to delegating and clearly articulate what they are trying to achieve with and through their teams. “Anderson and Adams argue that a compelling vision for what they are trying to create will support leaders in letting go of the reactive tendency to ‘do it myself’,” she explains, adding that while self-reliance might be effective in the short term, it won’t build the strength of the bench.

Referencing the work of American developmental psychologist Robert Kegan, Lorenzo points out that the stage of adult development is critical to a leader’s ability to create a compelling vision and follow through on it. “Kegan argues that if leaders are able to do the transformative work of evolving from a socialised mind (where self-worth depends on coherence with the external environment) to a self-authoring mind (where self-worth is inherent) they are better able to find the courage to act in alignment with their vision and values,” she says.

“In other words, if leaders are able to erase some of the terms and conditions they attach to their self-worth they can make the developmental shift to a self-authoring mind, from which they are better able to develop creative competencies such as effective delegation, which supports their leadership effectiveness.”

What happened to Rick?

In the case of a subject matter expert such as Rick, Segalo explains that the self-assurance that comes with holding onto their chosen speciality is often a source of ego for this “go-to person”, who now faces the dilemma that others might outshine him as he steps into an unknown leadership role.

There are any number of potential pitfalls that this could create. “That fear and ego could lead Rick to recruit people who still rely on him and aren’t quite on his level,” she says. “That blinds him to the fact that his progression depends on hiring someone who is as good as him so he can continue to advance.”

Other responses might be to fall into the micromanaging trap, or holding back by under-delegating in order to retain control. As much as it might seem counterintuitive, over-delegating is another outcome.

“The over-delegator does this for different reasons,” explains Segalo, noting how some MBA students start their learning journey feeling very self-satisfied that they have built strong teams who can run the show while they learn. “That’s the trap of over-delegating and abdicating responsibility,” she explains. “Delegating still means you have oversight. You’re still responsible for reporting to your upward leadership, so what’s your role if you are fully abdicating your responsibilities?”

Whatever form delegation challenges take, Segalo stresses that the “antidote is the realisation that fear and ego are a dangerous combination”. Like Lorenzo, she circles back to the issue of perfectionism. “This is reflected in the quality of work they do and, at an extreme and obsessive level, it plays out in seeking that same perfectionism in others. If these leaders don’t see that level of perfectionism, they can become disappointed and lose trust in others,” says Segalo.

The problem with Rick’s head-in-the-sand approach is that the current complexity in leadership requires a level of agility and responsiveness that cannot be achieved by those bogged down in operational specifics.

“To have an exponential impact in a complex context, leaders need to delegate,” says Lorenzo. “Delegation is a key tool for raising the strength of the bench and in a complex world leaders cannot rely solely on their own intelligence and skills.”

The four-step approach

When it comes to helping leaders achieve full delegation, Segalo likes to leverage Ken Blanchard’s situational leadership model. This is an effective method for understanding the aspirations of subordinates and identifying opportunities they want and support they might need.

“Right now, there is a bigger ask for managers to slow down and take that time. I would say that’s important before you start pushing stuff to people to do, because if it’s not what they are interested in, or if they are struggling, then you’ll get stuck in a cycle of poor performance. You have to lay the groundwork by fully unpacking and understanding where they are,” says Segalo.

As a starting point, Segalo challenges leaders to consider the development stages of all team members and then place each person on the Blanchard grid based on their current needs and the level of support required to progress. This should be a fully transparent exercise, she explains, noting that leaders need to learn which questions to ask and what is required to advance team members to the next quadrant.

“The intention is to help team members become fully functioning with tasks so you don’t have to think about them, and you can trust that things will get done,” explains Segalo, noting that different members of the bench will be at various levels. This means juggling inputs to suit the needs of all subordinates according to their place on the four quadrants.

For Rick, working with the four quadrants might look something like this:

- Directing

“When someone is new to something, be it a role or a task, you have to start in the directing quadrant,” explains Segalo. “This require telling them about the task, sharing clearly and telling them what your expectations are. You might micromanage in this space, and you might spend a month directing and showing, to ensure that expectations are clear. After a month or so, you move them into the coaching phase.” - Coaching

In this quadrant the team member starts dealing with the task on their own and the delegator spends less time looking over their shoulder. However, it’s not all hands off. “You are going to test it. You are going to meet frequently and check in and see how things are going,” Segalo says. - Supporting

The next phase is reached when the leader has sufficiently coached the individual through the process and, once they are comfortable, it’s time to start letting go of the reins while still holding that position of support as a sounding board. - Delegating

Finally, full delegation is achieved when the individual is able to run completely with the task or project. At this point, all stakeholders know who on the bench is assuming full responsibility and will go directly to this person with queries and problems.

What’s next?

Tools like Blanchard’s four quadrants are important navigational guides for leaders, and a solid way to make sense of the bench that leaders have at their disposal. However, the real focus remains on the leader’s own adaptive development.

Referencing Peter Senge’s work on personal mastery, Lorenzo emphasises an important question leaders should regularly ask themselves: “What is my current reality and how am I creating it?” Senge stresses that we all need to take accountability for our own personal development to help us navigate the complexities of the world.

“Jenny [Lorenzo] has done brilliant work around leaders realising that what is getting in their way of transitioning to that next level is their ability to delegate and get over being the go-to person,” says Segalo, adding, “Once you’ve let go of the detail, then you can begin to focus on the bigger picture.”

To arrive at this point, leaders need to recognise what is driving their short-term operational focus and their attachment to standing flatfooted on the dancefloor. After all, it is only once a leader takes his or her place on the balcony with the visionaries and the coaches that the real strategic thinking can kick in.

Battling with delegation?

Ask yourself these questions:

- Do I feel overworked and burnt out?

- Are there resources available to support me?

- Why aren’t I using them?

- Don’t I trust them?

- Is something else at play?

- Do I view delegation as a threat or an opportunity?

- Do I measure my worth by being perfect?

- What is my compass?

- What drives my decision making?

- What are my values?

- Am I able to shift my thinking around my own beliefs?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Former London Business School professor of organisational behaviour John Hunt once remarked that only 30% of managers could delegate.

- Of those, only one in three were regarded as good delegators by subordinates.

- For entrepreneurs the numbers are even worse. Gallup says only 75% of US business owners have high delegator credentials.

- Yet delegation is intrinsically liked to business profitability. A 2014 Gallup CEO survey of fast-growing private companies in the US determined that leaders with “high delegator talent posted an average three-year growth rate of 1 751% – 112 percentage points greater than those CEOs with limited or low delegator talent”.

Jenny Lorenzo

Jenny Lorenzo is an experienced organisational development practitioner, team and executive coach, and a process and learning facilitator. Jenny is certified by The Leadership Circle and uses the Leadership Circle Profile instrument, along with additional tools and processes, to enable leaders and teams to replace counterproductive reactive tendencies with creative competencies. This transformative process supports individual and collective leadership development, thereby unleashing collaboration, innovation, and agility. Jenny has supported the development of leaders and organisations across a range of sectors, helping leading companies across South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya on their journey towards effective learning, collaborating, and leading.

Thuli Segalo

Thuli is a systemic and team coach. She has held a Professional Certified Coaching accreditation with the International Coaching Federation since 2017. Prior to specialising as a coach, Thuli spent 18 years in corporate South Africa, working in a variety of leadership roles for blue chip organisations. She holds Master of Management in Business and Executive Coaching and a B.Com Honours in Industrial Psychology. Thuli also completed the GIBS Advanced Professional Business Coaching Programme. As a GIBS professional associate she coaches on the MBA, Global Executive Development Programme, General Management Programme and various customised offerings. She coaches on the GIBS Leading Women Programme and the Women Leaders in Health in East Africa for the Centre for Creative Leadership.