However, South Africa’s legislation is complicated and the country remains heavily dependent on coal. Carbon tax, therefore, remains a touchy subject.

In South Africa, where (according to the Department of Mineral Resources) coal remains an essential component in the country’s energy mix, accounting for about 70% of our primary energy consumption and 75% of electricity generation, carbon tax was always going to be contentious. However, as Lee-Ann Steenkamp, senior lecturer in taxation at Stellenbosch University Business School wrote for The Conversation, the country’s ratification of the Paris Climate Agreement in November 2016 signalled government’s commitment to responding to climate change and gave impetus to implementing the carbon tax.

Zelda Burchell, the carbon and energy manager at EY Cova, says that the approach has been complex. “Most countries use a simple model of either carbon tax or an emissions trading scheme. When government started developing the policy for South Africa, the idea was to create a simple carbon tax, putting a nominal tax rate onto direct emissions. But it then developed to include tax-free thresholds, so everybody gets a blanket ‘allowance’. This was aimed at softening the blow of the tax initially, with the idea being to gradually start phasing allowances out.”

She explains that there’s no need to 'earn' the tax-free allowance – it’s a given. But there are four other mechanisms available to help companies reduce their carbon tax burden, which require them to take action. These are carbon offsets, performance benchmarks, carbon budgets and trade exposure.

“Each one is almost like a science on its own,” says Burchell. “For example, the carbon offsets category focuses on growing a carbon market in South Africa through carbon projects, which is almost like an emissions trading scheme in itself. That’s what makes our legislation complex.”

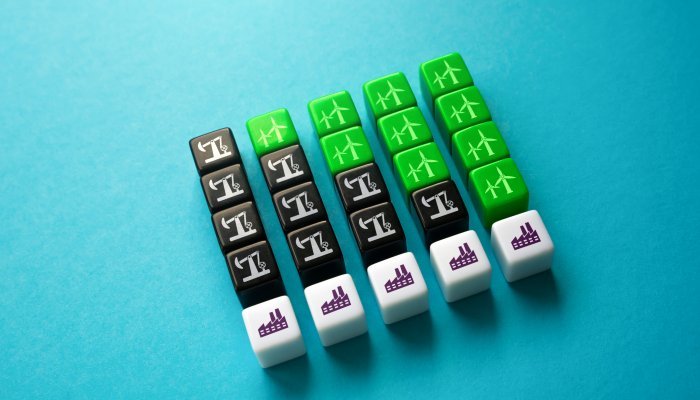

Carbon tax vs. emissions trading scheme

In its 2013 Carbon Tax Policy Paper, National Treasury gave the following explanation: “Carbon taxes work by pricing emissions directly, while emissions trading schemes operate by setting a cap on the level of emissions allowed. Firms are then allocated allowances (to be auctioned over time) which they may trade with other firms, depending on their abatement costs. Taxes provide certainty with respect to price, but no certainty with regard to emissions reductions. An emissions trating system (ETS), however, provides certainty of the emissions reduction levels to be achieved, but not of the resulting carbon price.”

Carbon tax content

Currently, direct emissions in South Africa are taxed at R144/ton CO2e (up to December 2022), which is much lower than in other countries. In its 2021 State and Trends of Carbon Pricing report, the World Bank notes that “experts say prices of $40-$80/tCO2e are needed to meet the 2°C goal”.

However, National Treasury communicated that it opted for a low rate to start, in order to “provide current significant emitters time to transition their operations to cleaner technologies through investments in energy efficiency, renewables and other low carbon measures”.

In 2019, the carbon tax implementation plan announced was to comprise two phases; the first running from 1 June 2019 to 31 December 2022, and the second phase from 2023 to 2030.

In Phase 1, the price of electricity would remain unaffected. But, in Phase 2, Treasury said, allowances would be phased down, and there would be a review of the impact of Phase 1, which would “be subject to the normal transparent and consultative processes for all tax legislation”. However, in February 2022, new policy changes were introduced.

New developments

On 23 February 2022, the National Budget Speech included several carbon tax updates, including an increase in the tax rate to R144 (roughly $9), effective 1 January 2022, with intentions to increase the rate by at least $1 annually until it reaches the rand equivalent of $20 by 2026 (to uphold South Africa’s COP26 commitments). From 2026 onwards, carbon tax will increase more rapidly to $30 by 2030.

Secondly, Minister of Finance Enoch Godongwana announced that the roll-out of Phase 2 would be delayed, extending Phase 1 until 31 December 2025, meaning most tax-free allowances continue until 1 January 2026.

However, Burchell says there is still much confusion surrounding the upcoming changes. “For some companies, the carbon tax impact has not been that significant yet, but for companies with significant emissions (such as in the cement and petrochemical sectors) the impact is substantial,” she says. “It is also becoming more material for the companies that have not been impacted as yet due to the changes proposed by National Treasury. Many companies have indicated that some of these were proposed without adequate consultation before publication and therefore came as a surprise to business. In addition, there is still significant uncertainty around the design of the tax for the second phase. National Treasury has not disclosed this information, which has been requested by business for a long time.”

For example, carbon budgets (essentially a cap against which an entity’s emissions are tracked), which have been voluntary until now, are expected to become mandatory from 1 January 2023. Burchell says there is currently no legislation in place, but the proposal of a carbon penalty of R640 if a company exceeds its carbon budget is concerning for business.

Burchell says what is most concerning is the pass-through of carbon tax on the price of electricity expected from 2026. “This will have an additional significant cost impact on every person in South Africa,” she says.

This is precisely what worries Dr Roze Phillips, GIBS board member and faculty at its Centre for Business Ethics. “Yes, we’ve got to consider climate change in the context of saving our planet, but we can’t do that without thinking about social justice and the just transition of people and communities to a zero-carbon world that is also economically sustainable for them,” she says. “We need to ask whether all voices are being heard. We have to look at the issue of carbon tax from a climate ethics position, and in terms of inclusive futures.”

Pursuing an inclusive future

“Many people don’t recognise that the preferred future – the most sustainable future that we are looking towards – is not the perfect future, but is the most inclusive one,” says Phillips. “It must be inclusive of all peoples, and it must be inclusive of planet. We can’t disregard one for the other.”

She cautions against viewing carbon tax as a silver bullet, and says that, as a capitalist solution to a social problem, it has its limitations. “I also worry that it’s a short-term solution to what is really a long-term problem. While it’s a great political vehicle, it’s indirectly another tax on the poor.”

The World Bank raises some of these concerns in an exploration of the limits of what carbon tax can achieve. “There are good reasons why governments may not want to use carbon taxes, and one of them relates to their welfare impacts,” writes Roumeen Islam, economic adviser at the Infrastructure Practice Group of the World Bank.

“For example, a carbon tax on fossil fuels is often regressive in its impact – hurting poorer people relatively more than richer ones. Even when it might be progressive, poorer people still suffer a welfare loss when prices rise, making their consumption basket more expensive. Devising transfers to compensate them for this loss is not a simple matter. Compensation systems may not be well developed, and it may be difficult to identify those hurt or to get funds to them. Thus, even if governments impose a tax, they may still baulk at levying a carbon tax high enough to reduce emissions to the extent they desire.”

Growing the carbon offsets market

Burchell says that one of the opportunities within South Africa’s legislation is that carbon tax can stimulate a carbon offsets market, where carbon credits are traded.

The background is a bit complicated, but basically, the idea dates back to when the Kyoto Protocol was developed in 1997. There was a project-based mechanism laid out called the clean development mechanism, which would allow countries with an emission reduction target under the Kyoto Protocol (Annex I Parties) to implement greenhouse gas reduction or removal projects in non-Annex I Parties to generate certified emission reductions (CERs).

In other words, these CER units would function as carbon credits that could be bought and sold to help countries meet their targets.

Burchell notes that while the market for “carbon credits” in South Africa fell flat for some time due to effective global oversupply of CERs, the implementation of carbon tax has resurrected the idea, but this time to help businesses to offset the carbon tax for which they are liable. “Suddenly, there’s a big demand for carbon credits, and not enough to go around,” she says.

Increased demand is good news when it comes to incentivising investment into qualifying green projects, such as solar power, landfill-gas-to-energy or reforestation. This creates opportunities for job creation, community upliftment and entrepreneurship.

“Creating carbon markets allows communities to get involved and to have agency,” says Phillips. “They can own a tradeable resource and benefit from it. It’s also a collaborative approach, rather than a punitive one, like a tax, which is important if we’re to collectively take ownership of our future.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Burchell says that carbon tax in South Africa is expected to become significant to such an extent that companies should already be to starting thinking about a completely different business strategy, including a net-zero roadmap.

- “Businesses need to model the expected financial impact for the longer term and to consider all the potential impacts,” she says. “This will help them to plan early on. Many exporters will also need to look into the carbon border adjustment mechanism. Companies exporting certain products to the EU are likely to pay significant duties on the emissions intensity of their products. This will be effective from 2026.”

- Key sectors that will be impacted include aluminium, iron and steel, and fertilisers.

Carbon tax and ESG

Whereas investors might once have bypassed countries with additional tax requirements, as attracting new foreign direct investment increasingly depends on having solid environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) in place, countries with carbon tax are likely to become preferred locations for setting up shop.