There are some medical spaces where experts such as Professor Paul Taylor of the Institute of Health Informatics at University College London really don’t want algorithms taking over. Mental health, for instance. We do need to ask ourselves what we should be using artificial intelligence (AI) for, Taylor told a forum at the UK’s Alliance Manchester Business School in 2024.

Low-level behaviour change problems like stopping smoking are one thing, he said, but “will we get to the situation where services are so stretched that people try and automate mental health services? I think that would worry me… although some people prefer to get help interacting through a screen.”

This conundrum reflects the feeling of uncertainty around certain applications of AI in healthcare. The problem is that the ship has already sailed and irrespective of the concerns, medically focused AI start-ups are booming. In January 2025 the Crunchbase list of global “unicorn” private companies valued at $1 billion or more showed that 11 start-ups had joined the ranks of the unicorns, including five from the healthcare sector. These included US healthcare model developer Hippocratic AI and India’s Aragen, a biotechnology R&D partner.

This “ongoing process of automation” will impact the workforce in sectors like radiography, said Taylor. “Some of the skills of the radiographer are no longer required because the devices will change the setting automatically, but that doesn’t mean that radiographers become unskilled. It means the job changes and the skills they need change, and that will happen faster as the machines get better.”

Is that cause for concern? Absolutely not, says Dr. Kathryn Malherbe, CEO and founder of Medsol AI Solutions. After all, AI technology has been used in radiology imaging for more than 30 years, having started out as computer-aided detection or CAD software for detection of irregular masses on mammography. “It’s not uncommon to use in our field,” says Malherbe, a radiographer and mammographer with 20 years’ experience. Certainly, deep machine learning and artificial neural networking are new, but she disputes that this will lead to job losses since “you still need the clinical empathy that comes from a specialist”.

Furthermore, while AI tools can help with clinical decision-making, “the ultimate choice and decision remains with you as the clinician, and it still remains within your built-in skills to read, assess and be there for a patient.”

Malherbe warns, however, that failing to adopt new technology could seriously disadvantage the naysayers. “The purpose of these tools is not to replace you, it’s to enhance your practice. The medical needs in our country are high and there are too few specialists, so using tools to make it easier and ensure everyone gets targeted care is the main goal for all healthcare professionals,” she says.

Improving women’s health through technology

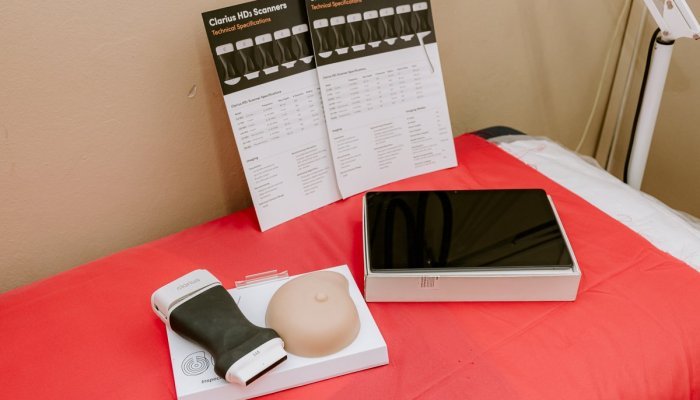

Malherbe speaks from experience. Her company holds the intellectual property rights to Invisio Diagnostic Imaging Solutions, the algorithm behind the Breast AITM Android app. A Wi-Fi-enabled ultrasound probe that leverages AI to analyse imaging data, the Breast AI breast cancer screening solution has a 97.6% accuracy rate.

The system produces a risk prediction based on the images, as well as follow up suggestions and next steps to provide support. This helps to fast-track referrals for patients in the public health sector; although physical capacity constraints remain a problem in accessing fast treatment.

Frustrated with the number of instances breast cancers were missed on ultrasounds, X-rays, and mammograms, Malherbe set about developing an algorithm that could segment, identify, and predict breast cancer. She started MedSol AI in 2019.

Trained using images of specific cancer and benign growths from across the spectrum of South Africa’s population, Malherbe aimed to enable earlier detection. About 80% of breast cancer diagnoses in South Africa are picked up in the advanced stages, compared with 15% in higher-income countries, which leads to higher mortality rates. This is particularly true for women of African descent, for whom breast cancer is often more aggressive.

Having initially rolled out the Breast AI app at Unjani Clinics in South Africa, MedSol has since partnered with AstraZeneca as its first South African A.Catalyst Network partner, operating in the Western Cape, Mpumalanga and at two locations in Gauteng. Currently, about 12 clinics as well as private doctors and breast surgeons use the app in South Africa, with ZimSmart Villages utilising the technology for remote medical services in Zimbabwe. “We are expanding further into Africa and we are in the early stages of finding a partner for Kenya, Ghana, and the Democratic Republic of Congo,” says Malherbe. “From an international point of view, there is a lot of interest.”

An ecosystem of smart solutions

MedSol also has another AI product in beta testing: a Wound AITM and monitoring solution for patients based in rural areas. Its partnership with AstraZeneca could potentially open the door for its liver disease AI product in Southeast Asia, where the rates of liver cirrhosis, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinomas are particularly high.

Solutions like these, believes AI thought leader Johan Steyn, are quality examples of how AI should be used in the medical space.

“The potential of AI extends beyond mere efficiency; it can transform patient care and enhance the healthcare ecosystem,” he says. “I’ve seen how these advancements can lead to significant improvements in healthcare delivery, particularly in underserved regions. AI’s ability to improve diagnostics, streamline operations, and personalise treatment is remarkable.”

Steyn singles out innovations such as e-mutakalo, an AI tool developed by the University of Johannesburg’s Institute for Intelligent Systems to remotely monitor vital signs, or minoHealth AI Labs in Ghana, which builds systems for radiology screening, diabetes identification, and lung disorders.

What’s next?

While there is no shortage of cutting-edge solutions hitting the market, Steyn notes that the next step is to consider the interoperability among AI systems. “Without collaboration between different platforms, we risk creating isolated silos that could hinder progress,” he warns.

One organisation that is well positioned to fill this interoperability role is IntriHealth and its medical AI healthcare ecosystem: Artificial Intelligence Medical Exchange (AiMeEx). Focused on servicing rural and peri-urban consumers in emerging markets, founder and CEO Mike Simpson explains that the platform covers key healthcare touchpoints like radiology, primary healthcare, preventative healthcare and homecare, with tele-radiology reporting already being undertaken for hospitals in Namibia and South Africa, with Zambia soon to follow. AiMeEx is also using blockchain donor funding to develop a secure electronic health wallet to house personal medical records.

While phenomenal technologies are currently being launched around the world, Simpson’s focus lies in meeting the needs of underserved individuals based outside big cities. This market comprises more than 55% of the African population. Recognising that under-resourced local healthcare providers are often overloaded and overwhelmed when it comes to technology adoption, AiMeEx offers a simple marketplace that connects healthcare providers with validated AI tools.

In addition to creating its own AI algorithms, IntriHealth’s AiMeEx platform provides a single point of contact and single pre-paid payment point for users. This means clients such as hospitals and private specialists only have to integrate their system with the AiMeEx platform, ensuring that the introduction of new tools or technologies can seamlessly be introduced – much like a traffic circle that keeps moving unimpeded as new AI products come in, update and go out. This level of interoperability is underpinned by a strong validation process for all AI solutions offered on the platform and selected for use in line with the client’s internal system and needs. This means that if a hospital’s chosen AI algorithm for a tuberculosis diagnosis is no longer best suited to a new X-ray device, that it can be seamlessly substituted.

“We are trying to keep abreast of technology all the time. If there are new AI developers, we’ve got the client’s curated data set and can run through the new offerings. If we get a better result we can offer this to the client,” Simpson explains.

This ease of use is an important consideration for AI start-ups and solutions. “Yes, AI is great, but let’s go through a process of evaluation. It’s not just plug and play. Let’s curate it. Let’s ensure that … we have followed due process, done our due diligence, to ensure that the most appropriate algorithm is used,” says Simpson, who touts the flexibility and choice offered by AI solutions as a significant gamechanger for healthcare in emerging markets.

Where do we stand on regulation?

AI thought leader Johan Steyn is part of the working group developing recommendations for a South African AI strategy. Regulation is notorious for taking time, but Steyn believes South Africa should have a regulatory framework by later this year.

As part of a team of some 80 individuals responsible for this guidance, Steyn notes that the focus will be Afrocentric although they’ve taken into consideration “about 200 different AI regulatory initiatives around the world and looked at their strengths”. While the African Union is releasing papers and opinions on the subject, the European Union’s AI Act is still the gold standard, although Steyn notes that all approaches must be adapted to consider South Africa’s historical context and socio-economic issues.

It’s also important to recognise that the more regulated AI becomes, the more it will hamper innovation. “Every region will have to balance that,” says Steyn, stressing that in healthcare strong regulation and privacy controls should always be a non-negotiable. He does note that implementation will also be tricky given that South Africa is still not getting it right in terms of digital privacy protections.

For UCL’s Professor Paul Taylor it is also important for governments to consider the systemic impact of AI tools. “A lot of the intended applications of AI will have unforeseen consequences in terms of major upheaval and major categories of employment disappearing. I sympathise with people not wanting to regulate too far and too fast when things are so uncertain, but in the healthcare environment we have strong regulatory frameworks around things classed as medical devices. What about things that manage to avoid being classed as medical devices?”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- One of the most promising areas for artificial intelligence (AI) applications is healthcare.

- African AI companies are focused on democratising healthcare and bringing down costs, while also compensating for skills shortages.

- The European Union is leading the way with regulation, but South Africa’s framework will be out in 2025.