When you start to look at how China has developed its industrial complex, you see that the Chinese economic model stands diametrically opposed to that of the US. While China draws its own fair share of controversy from critics around the world, no-one can deny that it has developed an industrial complex that will secure its long-term economic sustainability.

The growth and development of Chinese manufacturing

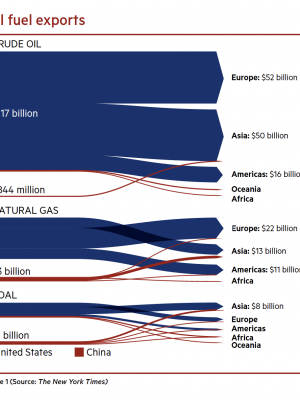

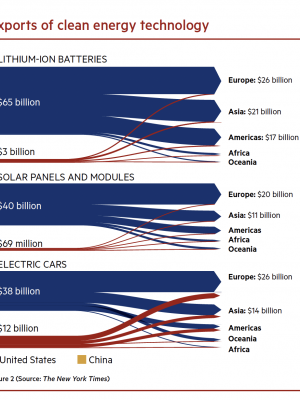

When we look at two graphics from Harry Stevens of The New York Times, we can see the sectors where China is leading global manufacturing and exports. Figure 1 highlights that the US is still relying heavily on fossil fuel exports to support its economy, while Figure 2 indicates that China has taken a different track. It shows that China is leading the world in terms of technology, including green energy production, electric vehicles, and batteries.

This future-forward development, however, has not happened by accident. Rather than China producing goods to compete on the global markets, its industrial innovation has stemmed from China strategically innovating and building capabilities to meet its internal economic needs. The proliferation of green technology that China produces – exporting nearly nine times the combined green energy exports of the rest of the world – was born from China’s need to address the massive pollution problem caused by its reliance on coal-fired power stations. According to Statista, as of July 2025, China has 1 195 operational coal-powered plants.

China’s economic and social strategy is outlined and cemented in the country’s Five-Year Plans – a policy adopted from Soviet Russia. These plans are comprehensive economic and social development blueprints which underpin China’s development. They outline broad national objectives, economic growth targets, and technological advancements. As 70% of Chinese industry is government-owned the government can then mobilise these plans through shifts in industry activity, together with the educational infrastructure to support the plan.

China’s economic principles and strategy have seen the country make significant strides in driving local innovation and growing its industrial complex.

A socialist support structure

While China has become a major exporter of goods, it protects its industries by keeping demand and supply local, thereby stimulating internal growth. Unlike the US’s economic model, which encourages manufacturers to source the cheapest products possible to keep costs down, thereby growing US imports, China has always encouraged local supply chains, which has ultimately driven its production costs down.

The effect of government support on industry is highlighted by Soviet Russia and China’s transformation of peasant economies into industrialised ones in a very short time – the only times such a rapid transformation has taken place. This is because neither of these countries subscribed to the free-market model that allows for the “invisible hand” – where economies rely on individuals, in the pursuit of self-interest, to unintentionally benefit society and markets over time. Both China and the Soviet Union drove industrialisation through their governments actively facilitating growth and development. Western models, on the other hand, which reject government interference in the marketplace and rely solely on market forces, have experienced slower evolutions of their markets.

China also supports a more fluid business environment. While the US tries to protect industries, highlighted by the phrase “too big to fail”, China, does not subscribe to such notions. A case in point is how China, in 2022, clamped down on the salaries and bonuses paid in the financial services sector. China criticised “finance elites” and an “only money matters” approach. As such, talent from financial services moved over to technology – DeepSeek’s Liang Wenfeng being one such example – thereby boosting that sector.

The intricate Chinese industrial complex

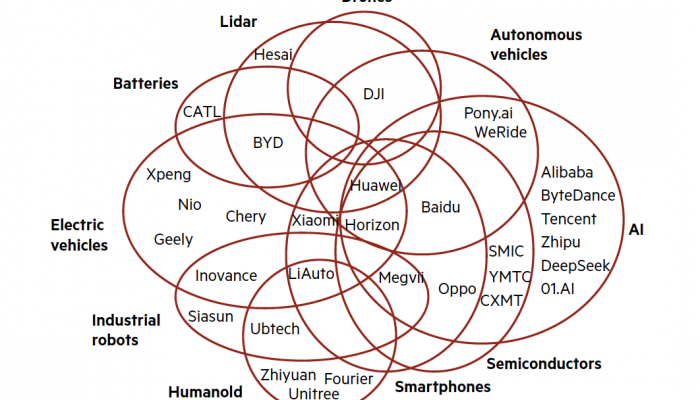

The Chinese industrial ecosystem is literally that. When you look at China’s industrial tech set-up, it is a web of interrelated industries that have developed off the back of each other (see Figure 3).

China does not just have a smartphone sector or an electric vehicle sector, it has numerous technology industries, which overlap with supporting sectors such as batteries and semiconductors. At the centre of this is Huawei, China’s largest tech company. Once these companies exceed a certain size or are in “critical industries”, the Chinese government ensures they get more government representatives on boards and have greater government oversight. This creates a compounding effect for the country’s industrial-policy efforts, says Kyle Wang, a Chinese technology entrepreneur and investor.

The system has four facets: supply, demand, technology, and scale. Supply and demand needs are met by the network of industries, meaning that manufacturers have a domestic market in which to supply goods. Wang gives an example: “Knowledge of polysilicon production is useful for photovoltaic cell and semiconductor chip manufacturing. Being able to make inverters is useful for solar, EVs, railways, and telecom equipment.”

Finally, having all the industries operating domestically, automatically allows for greater economies of scale for that product. This keeps the cost of production down and thereby ensures Chinese goods remain competitive.

In addition, China invests heavily in education and technological innovation. China’s approach to innovation, which is diametrically opposed to the US’s model – which attempts to encourage innovation through the use of patents and intellectual property laws – sees China insist on open-source technology, meaning that everyone has access to the technology being developed in the country, as the R&D from one industry can benefit a related industry. This ecosystem is not only benefitting China’s competitive advantage on the global stage, it is also fostering an acceleration in innovation, meaning that China is able to outperform its industry competitors in these fields.

China’s government, under the auspices of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, will also support any lags in the system. This is happening with China’s push to get Chinese automakers to reduce their reliance on foreign semiconductor chips by switching to locally manufactured products, further fuelling the local industry, ensuring that Chinese businesses are able to thrive.

China’s rare-earths domination

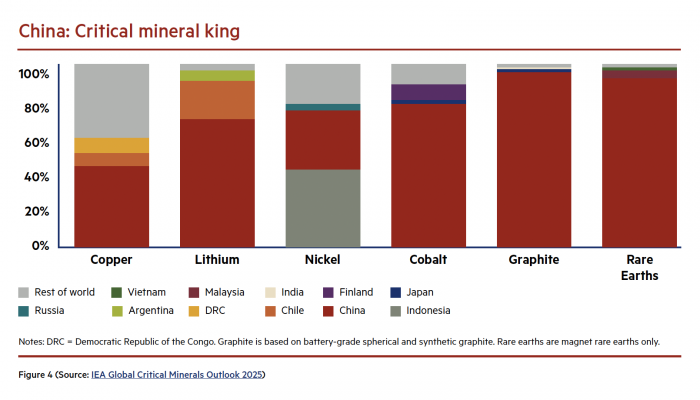

When we turn this discussion back to Trump and his global trade policies, there is no clearer example of the success of China’s economic philosophy and policy than its story of rare earth metals.

Rare earth elements are a group of 17 metallic elements that are essential for the production of modern technology, including electronics, renewable energy, and defence applications. While not rare in terms of availability as minerals, they are nevertheless widely dispersed, and difficult and expensive to extract.

The US, under the Biden administration, was more concerned with the availability of resources for its military complex than for technology, which resulted in America not investing in its tech supply chain. Rather, it decided to import rare earth elements from China. At the same time, however, China invested in education and research around rare earths. The New York Times reported, “Rare earth chemistry programmes are offered in 39 universities across the country [in China], while the United States has no similar programmes.”

In addition, while the US prizes profitability of production – The New York Times noted, “Making rare earth magnets requires considerable investments at every stage of production, yet the sales and profits are tiny” – the Chinese saw the value of rare earths beyond profits. So China supported this non-profitable industrial base to produce a good with very low margins of return, but one that is critical for other of its key industries.

Fast forward to 2025, and China now produces 70% of the world’s rare earths (see Figure 4). So when Trump wanted to impose 50% tariffs on China, China threatened to cut off supply of rare earths to the US. This would mean an almost instant halt to American electric vehicle and chip manufacturing. It also means that the US military cannot manufacture weaponry without China. As a result, China is the only country that Trump negotiated with as an equal in his tariff war.

A new industrial model

When the US moved away from manufacturing, it gave China the space to emerge as the world’s dominant manufacturing force. This allowed China to create a robust and healthy industrial ecosystem, producing a new economic superpower.

But this superpower has a new way of doing things. Perhaps Trump needs to rethink what it will take to “Make America Great Again”.

Huawei: Thriving in China’s industrial complex

Huawei is China’s largest tech giant and has been described by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang as the “single most formidable technology company in China.” The company dominates China’s smartphone market and is at the forefront of Chinese tech innovation (see Figure 3 in main story).

During Trump’s first term as US President, and then during Biden’s term, Huawei was labelled a national security threat to the US and was blacklisted. The US limited access to American-produced semiconductor chips. While this move was designed to lessen the technology company’s ability to produce and innovate new products, it had the opposite effect.

The US ban on supplying Huawei saw the company turn to Chinese chip manufacturers and ignited the company’s drive for self-sufficiency and innovation, which has allowed the firm to “conquer every market they have engaged in”, according to Huang.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- China is not an industrial superpower by accident; its success is strategically planned to support China’s needs.

- China’s government, through its five-year plans, has actively driven its industrial complex to innovate.

- China’s socialist economic model has seen government involvement in industry, which allows for the rapid development of industrialisation in different sectors.

- China’s industrial complex has been set up to allow China to be almost self-sufficient in terms of its supply chains.

- China’s rare-earth story is an example of how China plans ahead to ensure self-sustainability.

Prof. Kerry Chipp is an academic and researcher with extensive experience in marketing, consumer behaviour, and sustainable business practices. Chipp holds a PhD in Marketing from KTH Stockholm and is currently serving as an Assistant Professor at Luleå tekniska universitet in Sweden and as Adjunct Professor at GIBS. She has a background in both academia and professional research, with a focus on emerging markets, sustainability, and digital marketing.