The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation

Carl Benedikt Frey

Online only in South Africa – US$25.95 or £24.00

The future is a fearful place if you’re a human being. We are already surrounded by robots that build cars better than we can, by computers that can beat us not only at chess but also at the far more complex and fearsome game, Go. ATMs have replaced bank tellers and in no time at all, we’ll have driverless cars and trucks, completely automated fast food outlets and distribution centres without human beings. Machines are taking over and none of us will have jobs.

It’s a worrying view and one that has been around, at least in the West, since the Middle Ages. The first response to a new, labour-saving technology was usually for the monarch to ban it, but if that didn’t work, those whose livelihoods were threatened simply smashed the new devices.

Machine-breaking, as this practice came to be known, reached its zenith during the First Industrial Revolution in Britain, France and other parts of Europe. Nowhere more so during the period 1811-1816, when English textile workers formed a secret society called the Luddites. Their purpose was to destroy the new power looms which had already put thousands of hand-loom weavers out of work.

But surely, we ask as we look back, these people could see the long-term benefits brought by the Industrial Revolution, including the mass production of cheap goods that became available to ordinary working men and women, and the new jobs that were created in factories? Was this not all to the greater benefit of humanity? And, as we bring our gaze back to the present, don’t the same long-run effects apply? Are new technologies like Artificial Intelligence not also for the greater good?

Carl Benedikt Frey’s magisterial new work, The Technology Trap, examines this conundrum in great depth. It’s as much an economic history of the various industrial revolutions as it is an assessment of what might happen in the future. He’s clear on several points. Firstly, the social reaction to new technology will depend on whether it’s job-augmenting (helps you to do your job better), or job-replacing (puts you out onto the street).

Secondly, once on the street, it can be very difficult to find a way back inside. In those parts of England hammered by the new technologies in the early 18th century, as many as three generations of workers endured despair and misery before their economic fortunes turned. Frey contrasts this with the fruits of the Second Industrial Revolution, which began in about 1870, mainly in the USA, with the introduction of electricity and the internal combustion engine. Yes, lamplighters eventually became an extinct profession, but the new technologies were so useful and opened so many new opportunities that almost everyone was quickly able to find alternative work.

Thirdly, and perhaps most relevant today, is his view that the Fourth Industrial Revolution, with armies of robots marching side-by-side through the factories of the American rustbelt, is closer to the first than the second point above. Swathes of Americans – largely blue-collar, white, middle-aged men – have been cast into unemployment as the machines that they were brought up to tend don’t need them anymore. Like the hand-loom weavers, they have almost no prospects of ever again finding employment. Frey produces a litany of tragic evidence to illustrate the social polarisation caused by this – from alcohol and substance abuse, to the break-up of marriages and suicide. It is, he believes, why so many vented their frustration and anger by voting for Donald Trump in 2016.

The final sections of The Technology Trap throw forward, with a special focus on Artificial Intelligence and its possible impact on employment. Frey’s conclusion, in simple terms, is that if you have a good education, you’ll probably be OK, but if you don’t, you’re in trouble. He also sets out a list of practical steps and policy suggestions for government to mitigate against the crisis.

The Technology Trap is essential reading, not just to understand our past, but to give us the tools to allow us to think very deeply about the future.

After Dawn – Hope After State Capture

Mcebisi Jonas

Picador Africa - R290

Mcebisi Jonas has been inside the belly of the beast, literally. Summoned to the Gupta’s infamous Saxonwold compound, he was offered R600 million to become South Africa’s Finance Minister and hand over one of SAA’s prized airline routes to an Indian competitor. Thankfully, he turned the offer down and became an integral player in the exposure of then-President Jacob Zuma, the Guptas themselves, and what we now understand as state capture.

His new book is a detailed examination of how the nation found itself in this difficult place to begin with. Jonas believes that the economy, caught in a low-growth trap, was ripe for state capture, partly due to an over-dependence on commodity prices and demand, and financial portfolio inflows. He also blames poor policy choices, inequality, low-grade education, a lack of competitiveness and the fact that, in his view, we are being left behind in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Jonas draws it together by saying that “the essence of my argument is that the 1994 consensus – the social contract that enabled us to peacefully transition to democracy and which bound us together in the first two decades of freedom – is unravelling.”

His analysis of the problem, in all its manifestations, is trenchant and most probably correct. However, where After Dawn falls slightly short is in the second part of the book, where Jonas prescribes the remedies for this difficult set of problems. It’s a long list of exhortations to things like structural reform and a capable state but needs more detail in how he proposes that this should happen.

No question, though: if you’re thinking hard about South Africa’s future, After Dawn is a must-read.

Bitcoin Billionaires

Ben Mezrich

Little Brown – R325

What causes people to embark on wild, exciting and occasionally very profitable journeys? Throughout human history, one such motivator has been revenge.

For Cameron and Tyler Winkelvoss, the fuse had been primed and lit by one of the richest men on the planet, Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg. The Winkelvoss boys – both Olympic oarsmen – had been at Harvard with Zuckerberg and had been involved with Facebook from the beginning. But when Zuckerberg struck out on his own they were left in his wake. Hurt and angry, they eventually received a small settlement in Facebook shares, worth about US$200 million.

On their return to Silicon Valley to start out as venture capitalists, they discovered that they were distinctly personae non gratae. No-one wanted to touch their cash for fear of offending the behemoth that Facebook had become. They had become digital pariahs.

Fast forward a month or two and the twins, nursing their bruised egos, find themselves at a party on the Spanish island of Ibiza. That’s where they hear about something called ‘crypto’. Is it for real, or is complete garbage, and could it be a way of gaining revenge on Zuckerberg?

Writer Ben Mezrich tells the story of the Winkelvoss boys with a fine sense of drama. It helps that he had their co-operation, although this is far from an official biography. It also helps that as he was writing the tale, Bitcoin – the Ur-crypto – went through US$20,000 per coin, turning Cameron and Tyler into the first Bitcoin billionaires.

Since then, it has dropped back to about half its peak value and remains a source of great debate and controversy. Has Zuckerberg himself read the book, you might wonder? Impossible to say, but it’s worth noting that Facebook, earlier this year, announced the launch of its own ‘crypto’, Libra.

This story is not over yet.

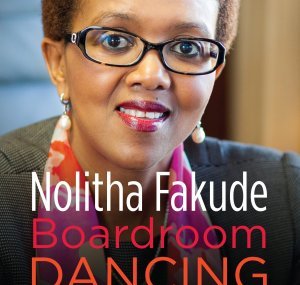

Boardroom Dancing

Nolitha Fakude

Pan Macmillan – R290

Nolitha Fakude is arguably one of South Africa’s most successful business leaders. That she happens to be female and black is almost incidental to her achievements; that she is female and black defines them. Her CV is a coruscating list of firsts, from being part of the first group of black graduate trainees at Woolworths, she has gone on to become the first female CEO and then president of the BMF, the first black female to be appointed to Sasol’s ExCo and she has now just been appointed to chair the management board of Anglo American South Africa. And those are just some of the highlights from a very long list.

Boardroom Dancing is her memoir, the story of her journey so far, and it’s important for three reasons.

First, it adds to the already extensive canon of writing about being black in both pre and post-apartheid South Africa. From a relatively prosperous upbringing at the hands of a hugely industrious single mother in the Eastern Cape, Fakude admits that she was expected to succeed. But race touches every aspect of her life. As she emerges into the business world, her gender also becomes a critical factor, especially at white, male, Afrikaans-speaking Sasol.

Second, it charts an important part of the development of the BMF, especially in the Western Cape in the late 1990s, and nationally in the early 2000s.

Third, Boardroom Dancing is also a highly readable, yet thoughtful manual on how to transform organisations. Sasol is once again the obvious example, but Fakude has chalked up notable successes at Woolworths and Nedbank. The chapter on the implementation of Operation Enterprise at Sasol alone is worth the book’s cover price.

One weakness: Fakude was also a director at SAA in the post-Dudu Myeni era. She quit, quite abruptly, for personal reasons as details of consultancy Bain’s links to the airline were revealed. What went on there and why did she leave? Alas, Fakude chooses to sit this dance out.