Today, there is new narrative suggesting that the latest hot technology, artificial intelligence (AI), will be a destroyer. Perhaps not of worlds – although the shriller takes do extend to this – but certainly of jobs.

The AI version of this argument may be novel, but the generic form is old. “Machines taking jobs” has spanned every innovation from the mechanical loom to the personal computer. A study of this phenomenon provides a mechanism by which technological advancement proceeds reliably through fear to prosperity. Joseph Schumpeter called it “creative destruction”.

Like any progression that matters, it is not a smooth curve. Growing pains are necessary. However, this is a path we must understand if we are to harness it. History will view AI Luddites like the originals. And markets will reward businesses that embrace it most effectively.

To pick one indicator of what is there for the taking, professional services firm PwC reckons AI could contribute $15.7 trillion to global GDP by 2030 (in constant 2016 US dollars).

Figure 1: Major technological breakthroughs over time

[insert figure 1]

Source: African Academy of AI (AAAI) (2025)

Foundational change

GIBS Professor of Economics, Finance and Competitive Strategy Adrian Saville puts AI in context. “First, this is not a tool,” he explains. “This is a foundational technology. It has the makings of a force that ushers in a new era. I’d put AI in the same category as electricity, telephones, or jet travel. All of these things enable entire ecosystems of productivity growth, rather than making their own, discrete improvements.

“Robert J Gordon talks about the ‘special century’ (1870-1970) when the likes of electricity, internal combustion and indoor plumbing dramatically improved living standards. And the ‘digital revolution’ (1996-2004) where mass adoption of computers and the internet nearly doubled productivity in the US. AI has the capacity to be even more impactful.

“AI can already write contracts and diagnose patients better than highly trained humans.”

Figure 2: Share of employees who reskilled due to AI in the past year (above) expected to reskill over next three years (below) (% of respondents)

[insert figure 2]

Source: McKinsey Global Survey of the State of AI (2024)

Greg Serandos, co-founder and CEO of the African Academy of AI, points to the ways in which technological changes improve our lives at a granular level. “The motor car meant the end of the road for stables and coach makers,” he acknowledges, “but that is better described as a market shift than destruction of jobs. It is hardly news to say that we must all update our skills throughout our careers. That will be harder for some than others, but predicting relative difficulty is difficult.

“In the horse-to-car example, you can picture the upgrade it made to lives. For one thing, streets were no longer covered in horse dung. The person who was paid to clean that up could likely reskill to perform car maintenance. I’d say that is an altogether more interesting line of work. Jobs that are, frankly, too boring or dangerous for humans are increasingly being automated by AI and robotics. Sure, it leads to some upheaval. But businesses that get this right will retrain and redeploy staff to do more enjoyable, productive work.

“Progress is messy though. Even the printing press, while enabling many wonderful things, allowed the printing of witch-hunting manuals. But, throughout history, new tech has elevated prosperity. There are no exceptions.”

What AI can’t do

Try prompting your favourite AI algorithm to “Start and grow me a business” and you’ll run aground. Ask the most expensive version of ChatGPT to “Complete this building” and you should expect a garbled attempt to assist.

“AI makes some things, like information and data, abundant,” explains Saville. “It lowers barriers. But it doesn’t eliminate scarcity. It shifts it. For business, things like trust, attention, originality, and judgment are relatively scarcer – therefore more valuable – in an AI era. These are foundations of strategy.

“Adopting AI alone is not a strategic advantage, just like having electricity is not a competitive advantage. We still need strategies to conjure up that sort of magic.”

“Technology doesn’t care, though. It can do all sorts of things better than us humans. With important exceptions. The warmth of a smile and the connection of human touch are the most obvious examples.”

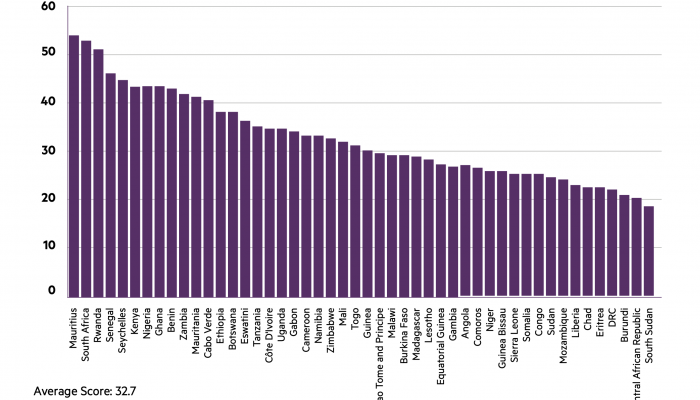

However, the list if things AI can’t do is shrinking. A chart produced by Stanford University (Figure 3 below) shows a staggering recent improvement in AI’s ability to answer PhD-level science questions.

Figure 3: AI technical performance benchmark versus human performance

[insert figure 3]

Source: AI Index Report (2025). Human-Centred Artificial Intelligence, Stanford University.

Winner takes all?

AI mimics earlier technological breakthroughs with its tendency towards monopoly power. AC versus DC electricity was an early one (1880s-1890s). Many readers will remember Betamax vs VHS videos (1970s-1980s). And Facebook vs MySpace (2000s). Wherever network effects apply and we all benefit from being on the same platform, the market equilibrium tends towards a single supplier. This can entrench outsized pricing power in a single entity, meaning fewer options and higher prices for customers.

“AI poses a major risk to vibrancy and equality,” warns Saville. “Markets need a healthy ecosystem of small- and mid-sized enterprises. Business, society, and regulators will have to deal with this wisely. We certainly need the vast investments that the likes of Nvidia and Alphabet can make to slash unit costs and democratise access, but we need a playing field that enables small entrants and growth despite a winner-takes-all market tendency.”

Labour-unleashing machines

Austrian-American economist Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) provides a lucid angle on what progress means to our lives. “In the precapitalistic age,” he argued, “the difference between rich and poor was the difference between travelling in a coach and four [horses] and travelling, sometimes without shoes, on foot.” But once industrialisation had done its work, “the difference between rich and poor [was] the difference between a late-model Cadillac and a second-hand Chevrolet.”

This applies to AI. It has made some people spectacularly rich. A 2024 poll of some 3 000 Nvidia employees (from a total of around 30 000) revealed that more than three quarters of employees were US dollar millionaires (Entrepreneur). Jensen Huang, the chipmaker’s CEO, is worth $124 billion (according to Bloomberg), making him the 12th-richest person alive

In the same breath, anyone with an internet connection today has access to AI-generated video production, a personal research assistant and navigation tools that not even billionaires had five years ago. Those who can spare R195 per month can subscribe to an app that will scan every meal and instantly calculate its calories and macronutrient content, giving dietary advice accordingly based on daily exercise and weight goals.

AI in action

Serandos’s firm both advises firms on AI adoption and builds the tech solutions. “Where the rubber meets the road, knowledge workers are exercising oversight over new-look business models,” he explains. “Big corporates are reimagining entire teams. Much of the output that was done internally or outsourced can now be compressed into one person who briefs an AI tool to produce, say, written content and visuals. The human then sense-checks it and might need a designer to brush up the imagery. An advertising campaign strategy that needed a large team and a few weeks can now be done in an hour with GPT, Gemini Deep Research or a competitor.”

What about board members? Can AI do C-suite? “This is where caution is needed,” advises Serandos. “Absolutely, board members need to adopt AI. A basic one is summarising board packs. But this is placing companies at risk. Most people are still using free versions of AI products. Or, if they use paid versions, they aren’t using the right security settings. Listed entities especially need protocols for this. On free packages, the AI algorithm is using you as the product. They’re learning from your data. That means you’ve lost control of your data. AI 101: for anything that matters, get the paid version and turn off data sharing.”

There is plenty of sexy AI going on in finance and the know-your-customer (KYC) space. Credit card companies are sitting on data gold mines, they’re putting code to work for predictive modelling. “Here the potential is endless,” exclaims Serandos. “There is enough data to establish that an unseasonally late snow storm in one region raises the chances of a spike in a particular spending habit or some other customer behaviour. This means sales teams can start preparing in advance, products can be rolled out, stock can be managed. Name a business and you’ve got potential for this to cut costs and boost revenues.”

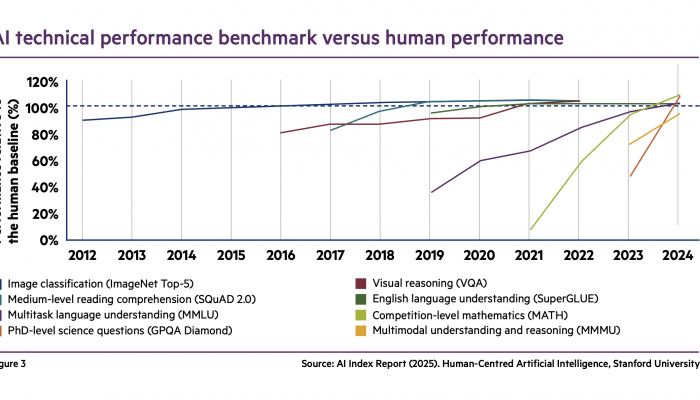

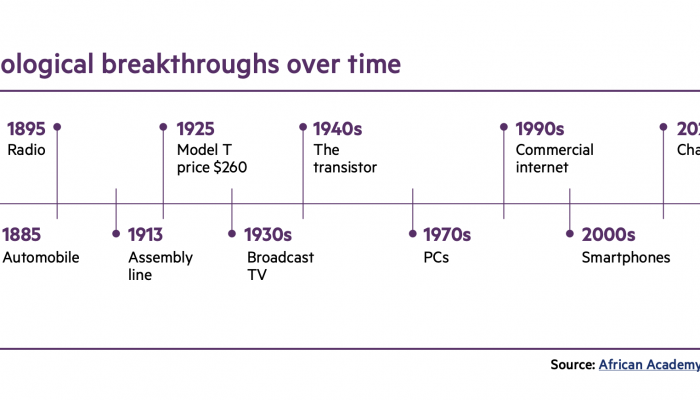

But potential has to be utilised. The Oxford Insights AI Readiness index suggests sub-Saharan Africa is poorly prepared. The swathes of white space on Africa’s map in Figure 4 (below) confirm this. The region ranks ninth out of nine in the report with an average score of 32.7, compared to the top region, North America, with a mean of 82.6.

Index authors argue that Mauritius, South Africa and Rwanda “stand out as frontrunners, with clear momentum in strengthening their AI ecosystems. Of their three measurement pillars, they find sub-Saharan Africa scores highest on data and infrastructure (42.06) and lowest on technology sector (23.98). This suggests that much of the hard assets are in place, and now the human capital and innovation need to catch up.

Figure 4: Country AI Readiness rankings (2024)

[insert figure 4]

Source: Oxford Insights (2024)

Figure 5: Sub-Saharan Africa, overall scroes

[there are actually two figures in the word doc from the author, figure 4, as well as figure 13. If you reproduce figure 13, please rename it figure 5?]

Source: Oxford Insights (2024)

What should business leaders do about AI? “Don’t be the factory owner who said, ‘Let’s wait and see if this electricity thing catches on’,” warns Saville. “Move fast. There will be dislocations, mistakes and plenty of lessons. But the only way forward is through embracing technology and with experimentation.”

Serandos echoes this sentiment. “If AI doesn’t take your job or usurp your business,” he warns, “someone who embraces AI will. As with all tech revolutions, AI fortunes favour the brave.”

The prize could hardly be larger. There are worlds to be created using AI.

GIBS Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM) founding member Ian Macleod studied a BBusSci at UCT before winning a scholarship from the SA Reserve Bank to read Journalism at Rhodes University. He completed his MBA at GIBS in 2017, where his research explored private equity investment in family businesses. Ian has a passion for power of narrative to drive commerce and markets. He joined CAMM as a founding member in 2018.